Home visits from education experts are improving outcomes for Philly kids in poverty

August 8, 2018

Category: Feature, Featured, Long, Results

August 8, 2018

Category: Feature, Featured, Long, Results

The benefits of a home visiting program in Ameesha Jackson’s North Philadelphia home were unexpected.

For her, it was watching her Parent-Child Home Program (PCHP) rep’s lessons and educational materials bring her whole family closer together. For her 3-year-old son Amari, it was finding a new favorite game: shapes and colors bingo.

“I think this program is helping [Amari] keep up with his brothers,” said Jackson, who has two other sons, Jayden, 8, and Mason, 5. “His brothers are already in school. They’re already engaging with other children.”

Home visiting programs are an effective way to introduce books and other learning tools to low-income Philadelphia children before they enter pre-K, said Malkia Singleton Ofori-Agyekum, the Pennsylvania program director for PCHP.

On a home visit, a service provider visits an expecting mother or a parent and young child in their home to discuss maternal health, early childhood development and parent coaching. According to a report by the National Home Visiting Resource Center, these programs can improve infant health, parent-child relationships and early childhood education.

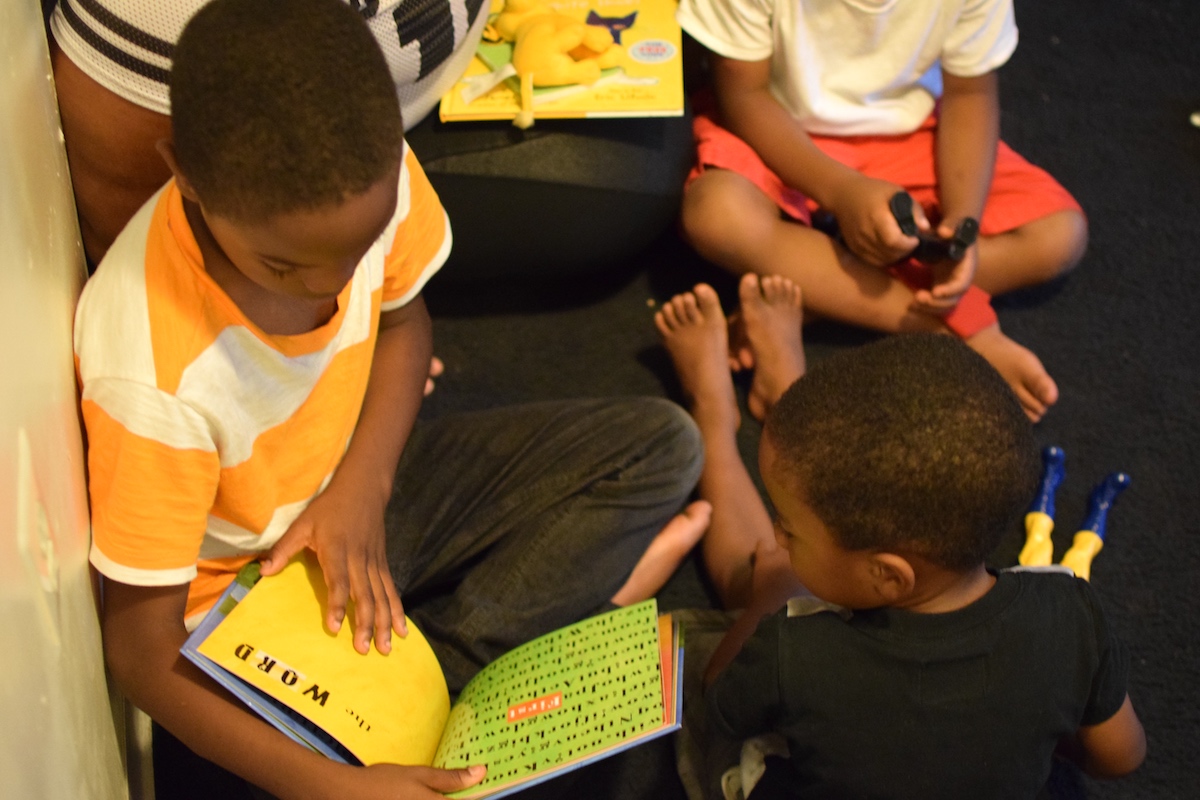

Jayden reads a book to his two brothers, Mason and Amari, and mother, Ameesha Jackson. (Photo by Grace Shallow)

Who benefits from home visiting programs in Philadelphia?

PCHP is one of 17 home visiting programs in Philadelphia County, according to United Way of Greater Philadelphia and Southern New Jersey’s Spring 2018 report, “Snapshot of the Home Visiting System in the Greater Philadelphia area.” There are 18 more in Bucks, Chester, Delaware and Montgomery counties.

All 35 home visiting programs in the Greater Philadelphia area serve low-income families, according to the United Way report; nationally, 74 percent of the 301,154 families served by evidence-based home visiting programs in 2016 reported an income below the federal poverty guidelines, which is about $19,000 for a family of three.

United Way Impact Manager Shira Badanes said one of the most important goals of home visiting programs is supporting early childhood education in disadvantaged homes.

Proficient reading skills in third grade is the most important predictor of high school graduation, which about 80 percent of children living below the poverty line fail to meet, according to a report by the American Academy of Pediatrics: Low-income children have “have fewer literacy resources within the home, are less likely to be read to regularly … all resulting in a significant learning disadvantage, even before they have access to early preschool interventions.”

“When people are in poverty, they’re surviving,” Ofori-Agyekum said. “They’re trying to figure out where’s food coming from, how we’re not going to put on the street. You’re not always thinking about, ‘Oh, I need to be talking to my child, reading to my child to make sure they have enough language and education skills.’”

Home visiting providers can strengthen children’s reading skills by bringing educational materials into the home and reading through them with the child, she added. This also models behavior for the parent to repeat — a facet of the “two-generation approach” taken by many home visiting programs (and United Way’s new funding priority).

“If you want to impact a child … it’s got to be [with their parent] because otherwise you’re just going in a hamster wheel,” Ofori-Agyekum said. “If you’re sending them to a parent who has no idea what you just did with this child, or how to support whatever that learning was, you just keep doing the same thing over and over again. You’re not building on the benefits.”

Per the United Way report, other populations served by home visiting programs in Philadelphia County include families receiving government assistance (100 percent), teen parents (82 percent) and families who speak a language besides English (76 percent).

What happens when they’re inside the home?

Besides all serving low-income families, home visiting programs in Philadelphia have many variations. The frequency and length of visits, necessary qualifications for staff, target age for clients and other factors differ from program to program. Here’s how three such programs work:

National Nurse-Led Care Consortium (NNCC)

NNCC offers two home visiting programs in Philadelphia: the Philadelphia Nurse-Family Partnership and the Mabel Morris Family Home Visit Program, an affiliate of the international Parents as Teachers model, said Kay Kinsey, the nurse administrator and principal investigator for NNCC’s programs.

- Target age: NFP starts working with first-time mothers who are usually in their first trimester until the baby is 2 years old. After that, interested families can be referred to Mabel Morris, which works with children until they’re 5.

- Length and frequency of visits: When a mother becomes a NFP client, a nurse will visit once a week for the first four or six weeks depending on her need. After that, it is every other week until the baby is born, then once a week for six weeks after the birth and then every other week until the program’s end.

- Reach: NFP is a national model practiced in 42 states and came to Philadelphia in 2001. Kinsey said the majority of the mothers reached by the programs are Black and Hispanic and concentrated in some of the city’s low-income neighborhoods.

- Highlights: NFP is entirely staffed by nurses. The programs also mandate weekly check-ins between nurses and their supervisors.

NNCC also offers the Nursing-Legal Partnership, which has served nearly 300 women in Philadelphia since 2016. All clients of NFP and Mabel Morris are screened for unmet legal needs and connected with a lawyer if necessary. Between March 2016 and June 2018, the top three reasons for cases have been income supports and health insurance (43 percent), housing (34 percent) and education and employment (6 percent).

Parent-Child Home Program

- Target age: PCHP works with families who have children between the age of 16 months and 4 years for a two-year period.

- Length and frequency of visits: There are two 30-minute home visits per week, meaning about 92 visits for the entirety of the program.

- Reach: Like NFP and Mabel Morris, PCHP is a national program. It came to Philadelphia in 2016 and has worked primarily in North, Southwest and West Philadelphia.

- Highlights: All PCHP staff members are from the communities they work in.

Ofori-Agyekum added that the program also ensures there is always a cultural and linguistic match between the staff member and family. For example, a PCHP staffer who who only speaks English wouldn’t be paired with a Spanish-speaking family. (Psst, the nonprofit also has a knack for turning clients into employees.)

Maternity Care Coalition (MCC)

- Target age: Karen Pollack, the VP of programs for MCC, said the organization works with expecting mothers and families from the child’s birth to third birthday.

- Length and frequency of visit: An MCC home visit can follow one of two evidence-based models: Early Head Start and Healthy Families America. Pollack said Early Head Start is the most intensive, with a weekly 90-minute visit; Healthy Families America is similar, with at least one weekly meeting during the first six months after the baby is born. After that, it varies depending on the client’s needs.

- Reach: MCC annually reaches between 1,500 and 1,700 families in Philadelphia, Delaware, Bucks and Montgomery counties, Pollack said.

- Highlights: Pollack said MCC is staffed by community health workers. They’re often knowledgeable about the neighborhoods they work in and often have experience working with children in other settings or have their own, she added.

The community health worker “shares language and culture and is able to help clients navigate systems,” Pollack said. “Not that nurses don’t do all of those things. It’s just a different model of providing services that … emphasizes more social support and connecting people to other resources.”

Ameesha Jackson poses with Mason, 5, Jayden, 8, and Amari, 3, in their North Philadelphia home. (Photo by Grace Shallow)

A bond for the whole family

PCHP’s home visitors leave all the materials they bring during visits, giving Jackson and Jesse Liverpool, the boys’ father, who isn’t home when the visitor comes because of work, the tools to play and bond with their son, too.

Jackson enrolled Amari, who was then a year old, in the program because she was looking for things to do with her youngest while her two older children were in school.

In the beginning, Amari was so shy toward his PCHP home visitor that he whispered answers to most of her questions. But he warmed during the visits twice a week and will graduate from PCHP next month. He starts pre-K soon after.

“Everyone [at PCHP] is warm and welcoming and they never make you feel uncomfortable,” Jackson said. “That’s a great advantage to have.”

Contributing reporting by Broke in Philly intern Evan Easterling.

Project

Broke in PhillyTrending News