How Penn is trailblazing philanthropy with this ex-Gates Foundation exec

January 14, 2016

Category: Featured, Funding, Results

January 14, 2016

Category: Featured, Funding, Results

Traditional philanthropy is folding into itself.

Those familiar models of giving are being eclipsed by an informed, influenced and intuitive iteration of what it once was.

- It’s capitalistic. It wants to make a social impact, but it wants to make money by doing so.

- It’s curious. Its impact can be super difficult to gauge and it’s language is loaded with vague terminology. That can make it divisive, which naturally makes it exciting.

- It’s calculated. It’s self-aware, data-driven and strategic.

It’s smart and intentional and different, and sometimes it feels like it’s made up of a million separate mechanisms barely moving in sync.

The Center for High Impact Philanthropy (CHIP) at the University of Pennsylvania feels it can play an important role by siphoning all of these moving parts into something graspable. For the past half year, the Center has been researching program-related investments (PRIs) — a vague type of impact investment strategy gaining popularity in philanthropy while simultaneously whipping foundation execs into a baffled frenzy.

(Just how vague? Know that this site you’re on right now is a PRI).

That confusion is largely due to a lack of institutional experience.

“I needed to educate myself,” said Barra Foundation president Tina Wahl at a conference last year. “I needed to get comfortable with some of the concepts so I could speak intelligently with people on my board from investment backgrounds.”

"The use of PRIs has been limited to less than two percent of the approximately $800 billion in foundation assets."

But institutions across the country are still dedicated to figuring this thing out — institutions like D.C.-based Case Foundation, which is actively sharing its work in the broad impact investing spectrum. Case Foundation’s VP of social innovation Kate Ahern recently said the foundation has been working to “help other family offices, foundations and others dip their toes in the water” for the past two years.

CHIP is doing something similar, but with a magnifying glass on PRIs.

“The use of PRIs has been limited to less than two percent of the approximately $800 billion in foundation assets,” said CHIP founding executive director Katherina Rosqueta. That’s why CHIP is working on ways to educate foundations on the barriers preventing the use of PRIs.

“The ultimate goal is to help funders get to impact faster,” she said.

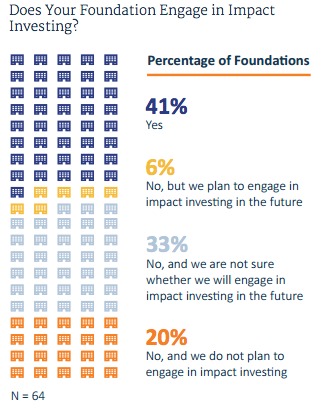

(The Center for Effective Philanthropy/Sonen Capital)

To help lead that research, Rosqueta and her team tapped former Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Chief Financial Officer Dick Henriques. A senior fellow with the Center and Wharton Social Impact Initiative since spring 2015 (and a Penn alumnus himself), he’s had great success with PRIs where others have floundered.

He hasn’t charted the entirety of this territory, but he’s trekked more of it than most have.

Above all, Henriques wants to use the university as a platform to articulate a consistent and wholesome understanding of how this type of investing works.

Navigating philanthropy’s new frontier

History will undoubtedly remember Microsoft founder Bill Gates for his tech behemoth and his globetrotting social campaigns.¹ History might not remember Henriques with the same level of grandeur.

But philanthropists should heed his work in PRIs.

The Global Health Investment Fund finances medical innovation in impoverished countries.

In his station at the Gates Foundation, Henriques devised the fundraising strategy that helped build its $108 million Global Health Investment Fund, enforced a private sector level of respect for metrics and had the foresight to restructure and stabilize the foundation’s leadership team before he himself stepped down from his post in September 2014.²

In April of 2010, Henriques was a former Merck exec who had opted for early retirement during the Recession. After two years of trying to enjoy retirement, Henriques found himself itching for work — for a job that carried some level of social resonance. The CFO position at Gates Foundation was the opportunity he had been waiting for.

“It was a perfect shift in terms of the type of finance professional they needed,” Henriques said. “Building some of the infrastructure for it to be able to function for a couple of generations was pretty rewarding.”

In his new position at the then-10-year-old foundation, Henriques was tasked with overseeing the foundation’s PRI portfolio.

Impact investing terminology, explained

Here’s an important thing to know: Impact investing is a term that, at its very core, is any monetary investment expecting both a positive social and financial return. It’s generally accepted across the social impact spectrum as an umbrella term.

Five things to know about impact investing:

- Four terms are often tossed around interchangeably: program-related investments (PRIs), mission-related investments (MRIs), socially responsible investing and impact investing. Of the four terms, only PRI is grounded in actual IRS rule.

- Almost nobody likes the term impact investing except for actual impact investors (a small sect of VCs and angel investors funding social enterprise). Sometimes, even impact investors get irritated with the label.

- That discontent stems from the fact that the term “impact investing” is not exclusive to socially-conscious VCs, but shared by business-savvy private foundations as well.

- The trouble with that dualism: private foundations very rarely make equity investments. It’s legal, but the risk is too high for most foundations’ appetite.

- That’s why many foundations settle for making low-interest loans, which can be a type of PRI.

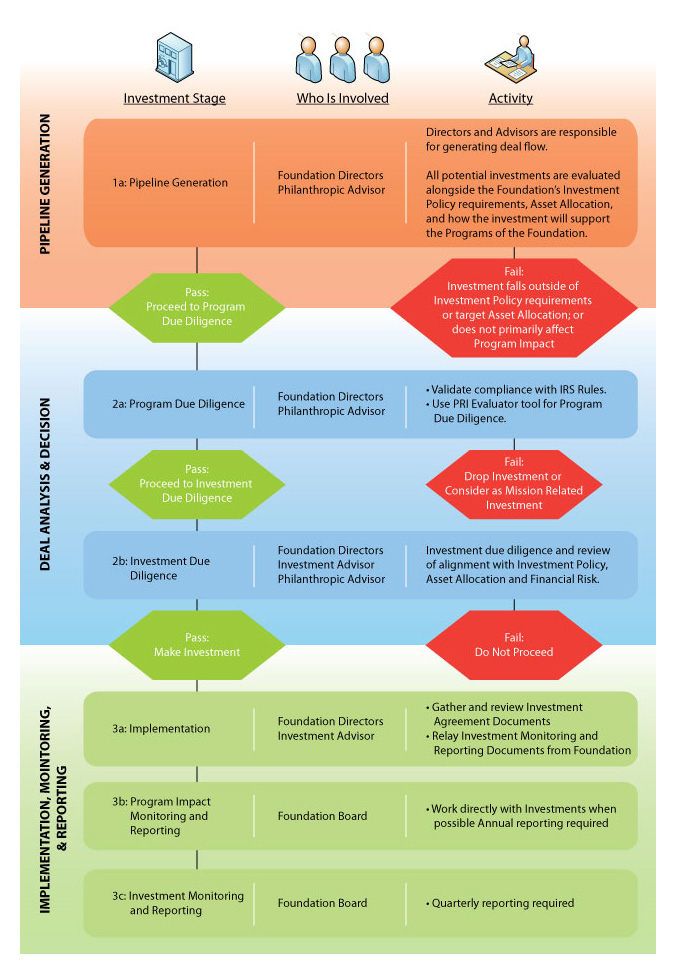

One more note: The primary purpose of a PRI has to be philanthropic and aligned with the foundation’s mission. Regardless, it can still be a pretty risky financial move and foundations need to do proper due diligence before making a PRI. Many private foundations, however, don’t have the capacity nor the in-house expertise to do proper due diligence.

How foundations can amplify their PRI portfolio

Process for making PRIs (KL Felicitas Foundation)

For what it’s worth, neither capacity nor expertise are lacking at the Gates Foundation. It’s widely considered the largest private foundation in the world, so resources are plentiful.

It’s 2010, and Henriques just walked straight out of a failed attempt at early retirement and directly into an executive position at the world’s largest, albeit quite nascent, private foundation. That foundation also happens to bear the name and reputation of a technology demigod.³ Henriques said he had a goal in mind for the foundation’s $50 million PRI portfolio before his first day on the job.

He wasn’t kidding.

From 2010 to 2014, that PRI portfolio skyrocketed from $50 to $700 million — that’s 1,300 percent growth over the span of four and a half years. For reference, in 2013, the Rockefeller Foundation’s PRI portfolio was $23.9 million.

(Fun fact: The term “impact investing” was coined by the Rockefeller Foundation, and so the dwarfing of its PRI portfolio by Gates’ portfolio from the starting block — the fact that the Gates Foundation was willing to put that much money towards this form of investment — lends to the increasing credibility of PRIs.)

$50 to $700 million, real quick.

The sheer dollar amount is impressive, sure — but given the bottomless money pit that is Gates’ bank vault, the real marvel here is the level of activity (as of last spring, and in vaccines alone, the portfolio included 10 PRIs in 10 different ventures). Here’s how Henriques said he and his team did it:

- Find Capital. Easier said than done. Gates himself, Henriques said, was a “strong advocate,” who shelled out the funds necessary to get the PRI portfolio a kick-start. (Tip: Get yourself a Bill Gates).

- Build your team of experts. Some of that money was funneled into capacity-building efforts, and the PRI team soon grew from two full-timers to 12. That’s an in-house knowledge base most private foundations don’t have access to.

- Find your focus. Henriques and his team focused on health first, because there was enough opportunity “at the leadership level in global health” to warrant considerable investment in vaccines technology.

This is where it gets playful and interesting. Henriques and his team pushed the envelope in terms of what a PRI could be by experimenting with types of transactions. For example, when Gates Foundation made their initial PRI in vaccines in 2011, they did so by cutting a deal with the vaccine manufacturer. The deal guaranteed the purchase of a particular volume of product over a five-year span.

“We knew the landscape better. Our perspective and appetite for the risk was different,” Henriques said. “We knew the world ultimately would pay [for the vaccines], it just wasn’t obvious to the manufacturer that that would be true. So we got significantly lower prices for vaccines as a result of providing that guarantee.”

Again, Gates Foundation is massive. That’s exactly why Henriques’s time building its PRI portfolio is so important: It’s evidence that this thing can work.

Still, Henriques said, making even one PRI is a strategic decision that must be made unilaterally across foundation leadership. That’s why CHIP’s work in PRIs will be so important.

“We’ve learned a lot, but need to start articulating more of what we’re doing and try to figure out what we could do on a practical level to make it better, not just put out a lot of commentary,” Henriques said. “The work isn’t finished, by any means. It will never be completely finished. But it’s a work in progress.”

FOOTNOTES

¹That myth will certainly be supplemented by this video footage documenting Gates’ athletic prowess.

²Henrique’s departure also snapped some wires within the tightly-wound Bill Gates conspiracy theorist blogosphere.

³A tech demigod who was also once an unfortunate and unsuspecting victim of the universe’s only known Dutch “pie terrorist.“

Trending News