Americans want fewer prisoners. What’s art have to do with it?

November 14, 2017

Category: Feature, Featured, Long, Results

November 14, 2017

Category: Feature, Featured, Long, Results

It’s a dreary spring day outside of SCI Graterford, but the dingy auditorium in Pennsylvania’s largest prison is brought to life with the sounds of percussion, strings, beats and jubilant voices.

The group of 25 men has gathered for their regular Monday afternoon music workshop, run by Songs in the Key of Free, a year-old music nonprofit. Every week, volunteer cofounders August Tarrier and Miles Butler bring music instruction and songwriting to Graterford, a state prison located in Montgomery County about an hour outside Philadelphia.

Whatever you think of a prison, Graterford probably meets the expectation. Built in the 1920s to replace the now-tourist attraction Eastern State Penitentiary, the sprawling industrial footprint on former farmland was built in a different era of criminal justice. Some of its 3,300 inmates are on death row. The grounds include a prison farm and guarded watchtowers. There’s an underwear plant, a barber school, outdoor workout yards between cell blocks. The entire campus will be replaced in Summer 2018 by the high-tech, $400 million SCI Phoenix immediately to its east.

But for now, these inmates play music in the old auditorium reminiscent of a neglected high school’s. The 25 participants — many of whom are lifetime musicians, and many of whom are in Graterford for life — write lyrics, make beats and play instruments individually and in small bands. They also perform inside the prison and “outside” to the public via professional musicians playing the songs the inmates have written at places like Philly’s Painted Bride art center and Eastern State. When the pilot workshop launched last year, it reached its small max capacity almost immediately and hasn’t emptied since.

In one corner of the auditorium, away from the other huddles of musicians wearing standard issue maroon jumpsuits, an infectiously cheery man named Bizzy plays tenor sax and flute. His quieter companion, Mouse, is on keyboard, and the two middle-aged inmates — both longtime musicians — play a few tunes while I ask about why they come.

Bizzy says, in part, it’s because of the caliber of musicians who are brought in to teach, including some from the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music along Philadelphia’s tony Rittenhouse Square. (You could hardly pick a more distant place from Graterford than the Curtis, with its student acceptance rate lower than Juilliard’s and alums such as world-known pianist Lang Lang.)

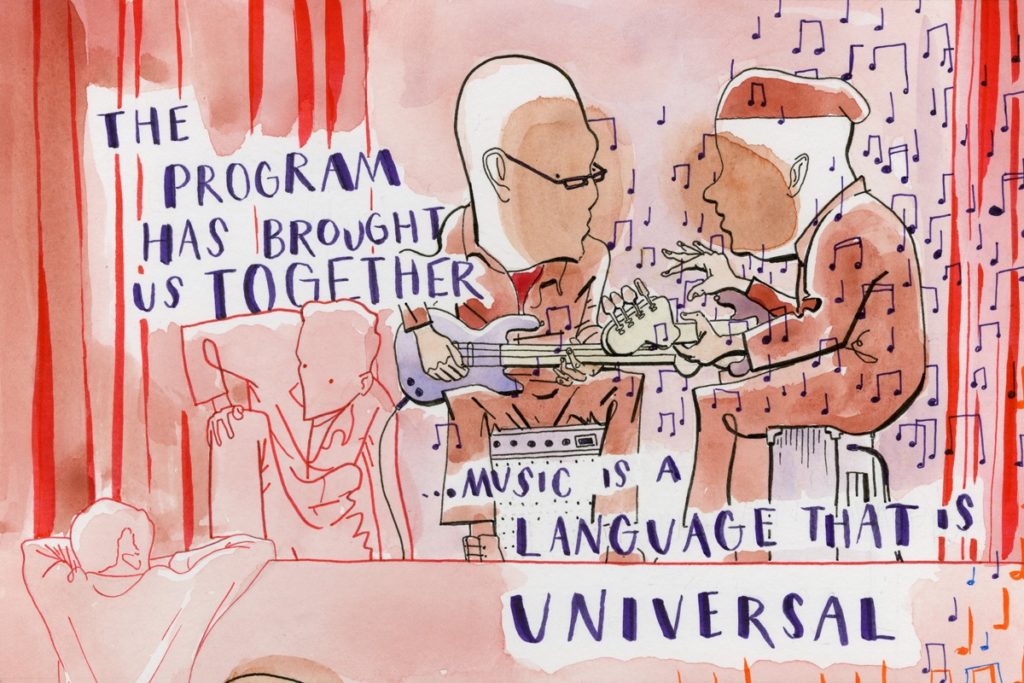

But it’s also because “this program has brought us together.”

Bizzy looks around, grinning, at the two dozen men in the cacophonous hall representing a range of ages, from the young to the gray-haired, and all stripes (except for, of course, the uniforms that serve as an equalizer) as they strum guitars and tinker with synthesizers. He adds: “You have different cliques. They would’ve never played together before.” Music, he says, “is a language that’s universal.”

Mouse tells me he likes it because “when we’re playing, it’s like you’re not in jail.” Mostly, though, Bizzy and Mouse want to talk music. They laugh about one guest performer who visited the workshop, an upright bass player from the Curtis. Bizzy imitates his fidgeting playing style, eyes wild. Soon, I’m laughing, too. Then he plays me “Smooth Operator” on tenor sax.

It’s a nice scene, these two genuinely talented older men hamming it up for the benefit of a stranger. You almost forget you’re in a state prison, and that many of the musicians milling about have no chance at parole.

The state of Pennsylvania spends about $2.5 billion per year to house 50,000 inmates, which averages out to $50,000 per person. The longer a person is locked up, the more the state pays — which is why reducing both sentencing time and the frequency with which inmates cycle in and out has become a bipartisan priority in recent years, following decades of tough-on-crime policies.

The last generation of criminal justice reform is largely based on the idea that rehabilitation isn’t just good for inmates, it’s cost effective for society, too. The Obama administration made waves when it pushed to reintroduce Pell Grants to support college studies, backed by research showing it reduced recidivism. The arts are hoped to be a natural extension: Though there have been few formal studies, there is ample anecdotal evidence that arts programming keeps inmates from acting out while incarcerated, thus reducing their time spent in prison overall.

It also seems to help them stay out, because those who’ve developed or nurtured an artistic passion while inside tend to seek out those healthy, supportive communities once they’re released. Songs in the Key of Free was inspired in part by the Californian legacy of Actors’ Gang Prison Project, an in-prison theatre program founded by “The Shawshank Redemption” star Tim Robbins that’s been found to cut the recidivism rates of participants in half and cut in-prison infractions by 89 percent by giving participants an outlet for their emotions and tools for controlling them.

Next year, the fledgling Songs in the Key of Free will put out its first album of participants’ music, recorded entirely in Graterford. Though there are other art and music programs in this and other state prisons, including one long-running art program by Philly’s famous Mural Arts, this one is likely the first of its kind, album and all, in Pennsylvania, if not the country. (A decade ago in Graterford, there was an inmate-run music workshop, but it was shut down after VH1 shot a documentary about it that sparked an outcry from victim advocates.)

After the album is completed, the program’s future is unclear. Prison programs are generally financed in one of two ways: government or philanthropy. Songs in the Key of Free relies on the latter. It’s staffed by volunteers, but its shoestring budget — for things like instruments, recording equipment and concert production — comes from individual donations and the occasional small grant.

The cofounders and their handful of other dedicated volunteers want to be able to serve other incarcerated populations in the Philadelphia area, not just Graterford. But with no stable or significant funding, it’s hard to keep what they have going alive and also start new workshops elsewhere.

Over the last decade, Pennsylvania and Philadelphia have witnessed a shift in their approach to criminal justice. Progressive reentry policies within the city have gained traction recently, spurred by the election of far-left-leaning district attorney candidate Larry Krasner and a $3.5 million MacArthur Foundation grant aimed at reducing the city’s prison population. The new state attorney general, Josh Shapiro, has said that reducing recidivism is a top priority. Philadelphia has a cross-sector Reentry Coalition working to support that population, too. Slowly, there’s a sense that making prisons something other than places of punishment might be a good thing.

But the fate of Songs in the Key of Free begs the question: Is arts programming important for Pennsylvania’s prisons? And if so, should a state that believes in the value of such programs have a role in maintaining them?

Experimental inmate programming in Graterford is not a new concept. The prison’s proximity to Philadelphia, combined with the city’s abundance of reform-minded organizations, means that the facility’s inmates have a unique opportunity to access arts workshops, music classes, mentoring programs, pre-release preparation and more. Take Temple University’s long-running Inside-Out Prison Exchange, which brings North Philly college students to the prison for co-learning, as just one example.

The Songs in the Key of Free founders started up their work with a twofold mission: uplift the spirits of the participating inmates through songwriting, and share their work with those on the outside. Lyrics from a song written by inmate Cody called “I Can’t Breathe,” inspired by the dying words of Eric Garner, indicate that duality, the self-awareness of their predicaments:

“When hands that serve are squeezin’ life from me / And those who lead are deaf to all our pleas / They’re blind to all we see / Refuse to give even an inch it seems / And I can’t breathe.”

Cody has been writing songs for five or six years, he tells me. He participates in the workshops because of the collaboration it inspires between inmates. “That’s a challenge in here,” he says while strumming a guitar in a plastic auditorium chair. “This environment pushes on you emotionally but songs [help you express yourself]. There’s a lot of gold to mine here.”

Songs in the Key of Free cofounder Tarrier had been teaching creative writing classes at Graterford through Villanova University since 2008 before she and Butler debuted the workshops there in Fall 2016. It’s been a transformative experience, she says: “We are really deeply bonded to our inside musicians. We’ve been seeing this unfolding of self, for us and for them. That’s happened through building trust and through reciprocity.”

Graterford Superintendent Cynthia Link said she encourages arts programming in her prison, not just because it’s a neat thing to do but because prisoners actually behave differently when they’re involved in the programs.

“They are more willing to follow the rules because [they realize] ‘There’s something of value that I may lose if I do not,’” she said. “The men, especially, who are involved in the programs are like, ‘Superintendent, don’t worry about anything, we got this. You’re not gonna have any trouble, you’re not gonna have any problems.’”

"We’ve been seeing this unfolding of self, for us and for them."

She finds Songs in the Key of Free to be a stand-out group, even among other high-quality programming. When I first mentioned the program, she broke out into a grin and said, “I just got chills.” And she believes that the positive change in inmate behavior may prove statistically significant: The prison has decided to start compiling data to track the frequency of behavioral infractions among program participants.

That should be welcome news for advocates of such programs. Nationally, data about the benefits of arts programming in prisons — or its impact on recidivism — is scarce.

The research that does exist, however, is telling: One study from 2014, conducted by California Lawyers for the Arts about a state-funded program there — more on that later — found that two-thirds of those surveyed (49 inmates in four prisons) said their arts classes helped them get along better with fellow inmates. For the latter, longevity mattered: Participants who stuck through the program for five years or more were nearly twice as likely to be better behaved than those who were in for a year or less.

Another study, published in January 2017, found that over 90 percent of 63 participants across five prisons said they were better able to communicate with others after participating in the programs, and 92 percent said they enjoyed better relationships with other inmates; about 80 said the same of prison staff.

The point is, in an era of criminal justice reform, the transformative power of the arts shows exciting early signs for therapeutic and socializing gains, but it takes years of commitment to see the big impact.

One Songs in the Key of Free participant named Robert, an older man with a graying beard, told me that the workshop is important for him because he thinks it’ll be a key to helping him stay free once he’s released: “I’mma never stop playing music.”

Robert is a drummer who had a band before serving in Vietnam, and he said he plans to continue playing after he’s released from Graterford. “It’s therapeutic,” he said. “I need something to keep me busy and out of trouble. I be in that [recording] booth every chance I get.”

At least 95 percent of all state prisoners will be released from prison at some point. There are no recent, comprehensive studies about how the arts impact a person’s likelihood to be re-incarcerated. However, one conducted over seven years in California during the 1980s found that nearly 70 percent of a sample of inmates who participated in the state’s arts programming did not return to prison within two years of being released, compared to only 42 percent of the general California reentry population.

Tarrier is not surprised by these positive results and thinks it’s obvious that Pennsylvania should want her group to continue its work: “Wouldn’t you rather have someone who’s been hanging out with Songs in the Key of Free for the past 10 years, rather than in the hole?”

Therein lies the rub — it does. But paying for it is a different story.

Secretary of Corrections John Wetzel is known for being a blunt guy. When he stopped by Philly for the Democratic National Convention last year, he publicly shared his frustration with the “bloated” criminal justice system he had inherited, which offers “no return on investment” — indeed, low-level offenders who enter the state prison system leave more likely to commit a crime in the future.

The former college offensive lineman is especially blunt when asked what it would take for the state to allocate funding to sustain programs like Songs in the Key of Free: “Generally, taxpayer dollars go to evidence-based programs, [usually] required programming” — drug and alcohol treatment, sex offender therapy, mental health services, he said.

“I think anything that keeps individuals productively occupied makes sense,” he went on, referring to art and similar non-essential programs. “In particular, just having individuals who are incarcerated get exposed to things like that, it’s a good thing.”

That sentiment, in and of itself, could be seen as progress. Robyn Buseman, who runs Mural Arts’ Restorative Justice program, which operates both inside Graterford and with returning citizens, shared that “normally, criminal justice people haven’t thought about the arts and the importance of arts programming in the prison system.”

Despite this, Wetzel said government funding for arts programming is another matter entirely. “I think we live in a political reality where it’s a non-starter,” he said.

"I think we live in a political reality where it’s a non-starter."

Consider the case of in-prison higher education degree programs. There’s strong evidence of their effectiveness in reducing recidivism: The RAND Corporation conducted a meta-analysis of 30 years of such programs in 2013 and found that those who participated had a 13 percent lower risk of recidivism.

Despite that positive showing, Wetzel said he’s gotten “pushback” from Pennsylvania residents for running the pilot college-level classes funded by Pell Grants, a program that benefits 115 inmates in six state prisons, including Graterford. Culturally, in America and in Pennsylvania, the public still expects “a punitive approach” to corrections, he said.

In other words, it feels bad to many taxpayers that felons should get to earn a degree, let alone learn the guitar, on their dime when they’re meant to be saying penance for their crimes. Wetzel said he’s tried to “open the doors of prisons” to the public via volunteer programs and TED Talks broadcasted from inside the prisons — “The Lady Lifers” song about women experiencing life in prison without parole went viral — in order to change public perception about the humanity of those locked up.

Still, numbers matter, which is why he doesn’t see a future for state funding for arts programs. The takeaway there: You need data to make a case for any government funding for prisons other than walls and guards, but even then, there’s no guarantee. The case for reform is still very new. And there is still scant research of these programs’ effectiveness in part because studies cost money to run.

“When you talk about the programs we’ve established and expanded, the approach we’ve taken is really trying to show a return on investment,” Wetzel said.

There is one place that’s tested the waters of government-funded arts: California. The state, known for progressive justice experiments, has gained national attention in the past few decades for its dedication of funding for arts in prisons. That comes largely through the California Arts Council’s Arts in Corrections program, which was created in the 1970s and has seen a recent revival following a decade hiatus after being defunded in 2003.

In the 2016-2017 fiscal year, Arts in Corrections distributed $6 million to all 35 of its state adult correctional institutions, with an anticipated increase to $8 million in the next. It’s a small slice of a big state’s $11 billion prisons budget, but it’s more than every other state’s allocation of zero dollars.

The process for securing California’s existing $6 million in funding for Arts in Corrections has been a combination of advocacy from California Lawyers for the Arts and a funder environment in which donors were willing to put money toward this policy goal, said California Arts Council Interim Executive Director Ayanna Kiburi.

“It’s been a combination of things: a strong partnership between us at the California Arts Council and [California Department of Corrections], support from the governor and legislature, and advocacy from the field,” she said. “Each did its part to help bring state-funded arts programming back into our correctional institutions. The state’s investment in the Arts in Corrections program acknowledges the strength of the arts as a cost-effective way to address rehabilitative and public safety needs.”

For places like Pennsylvania, though, even for arts programs with private funding, most are still operated largely on a volunteer basis and virtually none have the ability to study their impact. This leads to situations like that of Songs in the Key of Free. The usually cheery Superintendent Link is reticent when I ask about what she thinks needs to happen to get more programs like it in Graterford, and to keep them there.

“Everybody wants to change the world, but nobody really wants to pay for that,” Link said. “It has to come from the hearts of people who want to make a positive change.”

"Everybody wants to change the world, but nobody really wants to pay for that."

The lesson in all of this: Policymakers serious about criminal justice reform ought to look at real solutions, and supporting arts programming prisons may very well be one of them. But we won’t know for sure if funders interested in the subject don’t divert some funding to data tracking rather than programming itself.

Meanwhile, ask the men at SCI Graterford what they think of Songs in the Key of Free and they’ll give you poems in return.

One participant, Bomani, a large, deep-voiced man wearing a Muslim prayer cap, tells me the music making is about “giving a voice to where there is none, a voice that’s been smothered.” He adds: “Prison crushes the human spirit. The song goes further than the books. It crosses language barriers.”

Tarrier and Butler said they plan to run Songs in the Key of Free in Graterford for another few months as it wraps up recording for the full-length album; a crowdfunding campaign will kick off in December to fund its distribution. Then the program will move on to the federal detention center at 7th and Arch streets to teach choral singing to incarcerated women alongside the Anna Crusis Women’s Choir.

They’ve also been in talks with Link about doing a reboot in Graterford-replacement-facility Phoenix once it’s open and have been applying for grants to scale that work. But it’s hard for them to say now what exactly that reboot would look like, as there’s only so much volunteer bandwidth, and there are other inmates at other prisons who could benefit from a program like Songs in the Key of Free.

Before I leave the workshop during my spring visit, Bizzy plays me his remake of 1970s TV theme song “The Love Boat” with lyrics about Tarrier and her team — “August, exciting and new / When you’re here, you’re always cool.”

When playing music, he tells me, “you feel like you’re free. We got to do this to stay out of our head. This program has brought light in here.”

###

This story was edited by Technically Media Editorial Director Christopher Wink and The Reentry Project Editor Jean Friedman-Rudovsky. Illustrator Mike Jackson’s work was supported by The Reentry Project.

See the full illustrationTrending News