Yancey Strickler has been thinking about the larger structures that we live within. And he’s written his manifesto

October 25, 2019

Category: Featured, Long, People, Q&A

October 25, 2019

Category: Featured, Long, People, Q&A

Yancey Stricker always dreamed of being a writer.

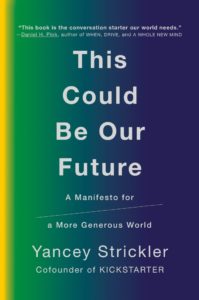

Before he cofounded Kickstarter, he wrote music reviews for the legendary Village Voice alt weekly from New York, along with Spin, Entertainment Weekly and other publications. After he left Kickstarter in 2017, he sat down to write his first book: This Could Be Our Future: A Manifesto for a More Generous World, by which he proposes to make business a tool for change.

Strickler will be the keynote speaker at Generocity’s inaugural conference — ADVANCE by Generocity — on Friday, November 1, and be part of a panel titled “Envision a Future Drive by You” with local leaders from the nonprofit and for-profit world, including Markita Morris-Louis from Compass Working Capital and Tiffany Tavarez from Wells Fargo.

In advance of ADVANCE, Generocity asked Strickler some questions about how Kickstarter has changed the practice of philanthropy, and about some of the wider changes he proposes in his book. Our questions are interwoven with questions from Create X Change in the following Q&A.

Generocity: Kickstarter has completely changed the way people give — and the way people ask to be funded. What lasting impact do you think it could have on philanthropic and grant making organizations?

Yancey Strickler: It’s made the process something that the public participates in. Everyone now has the opportunity and tools to propose ideas and create financial, moral, and communal support around them. This gives grant makers and other traditional givers the ability to not only see what spaces and ideas the public has interest in, it also gives them a window into what areas might be underfunded and allowing them to have a bigger impact in a more needy space.

Create X Change: How did your experience as Kickstarter’s CEO affect your view of the business world?

Strickler: From the beginning, our goal with Kickstarter was to help creative projects get made. The goal wasn’t to start a company. It was to make this specific idea that just so happened to be a company. And, because of who we as cofounders are, we were determined to do it right.

We didn’t raise lots of venture capital or growth-hack our way to success. We stayed small, lived within our means, and were sustainable from our second year. We converted Kickstarter to become a public benefit corporation, which legally requires the company to produce a positive benefit for society. All of these choices reflect the company’s commitment to its mission and values.

I say this knowing full well that tech’s focus on mission and values is a punchline at this point. And justifiably so. Everyone’s claiming to be saving the world when in actuality a lot of people are saving nobody while stuffing their pockets with cash. But in the case of Kickstarter, the company’s mission and values are very real. As a public benefit corporation, these commitments are legally binding. They aren’t just slides in a new employee onboarding deck.

"Everyone’s claiming to be saving the world when in actuality a lot of people are saving nobody while stuffing their pockets with cash."

My experience in the business world makes me optimistic about business as a tool for change. If and when compelling and self-interested reasons emerge for businesses to focus on something other than financial maximization, they can be convinced to do that. The business world’s greatest asset is its ability to evolve.

Generocity: How is a public benefit corporation distinct from a company like TD Bank (which is part of your book genesis story) that has a foundation that engages in corporate social responsibility funding?

Strickler: A Public Benefit Corporation is a new corporate structure where a company is legally required to not only to produce a positive return for shareholders, they must also produce a positive benefit for society at large. The company can lay out what those things are in a charter, and they’re held legally accountable to them from there on. That mission is made a core part of everything the company does.

Corporate good programs on the other hand, while doing real work and run by people who genuinely care, are extraneous to the company’s core goals. They’re almost like an apology for being so profitable. “Sorry for not paying enough taxes to pay for our local schools but we’re happy to pick up trash at this park once a month instead so long as there’s a sign with our name on it!” It’s not a signal of a real community commitment so much as it’s a brand signal of one.

Create X Change: How did the idea for This Could Be Our Future originate?

Strickler: It started by watching my old neighborhood, the Lower East Side of New York City, change. I lived there for over a decade as it transitioned from a neighborhood of small businesses to the neighborhood with the highest concentration of chain stores in all of New York.

The crystallizing moment came in 2014 when Mars Bar — a legendary punk dive bar and an institution in the Lower East Side for decades — became a TD Bank. There were already three other TD Banks within a 15-minute walk from that exact spot. It made no sense.

A Wall Street Journal story at the time found there were 500 more bank branches in New York City than a decade before. I had this flash: those 500 new bank branches meant hundreds of neighborhood businesses like Mars Bar closing. It was a devastating thought.

At the time I was the CEO of Kickstarter. I’d been invited to give a speech at a big tech event called Web Summit in Ireland. I decided to tell the story of Mars Bar and TD Bank, and connect it to the rise of movie sequels and other ways the world was becoming more of the same. Why was this happening? Because we’d come to believe that the right choice in every decision was whichever option made the most money. This was always the “why.” I gave this idea a name: financial maximization.

It struck a chord. The audience responded, as did people online later on. I realized that by sharing something simple from my own life (why are there banks everywhere?) and connecting it to these bigger ideas, something that was hard to see became easier to see. This book continues that idea.

Create X Change: In the book, you discuss hidden defaults in decision-making. What are some of these defaults and perspectives?

Strickler: The book is focused on a particular hidden default: the belief in financial maximization. This is the idea that the right choice in any situation is whichever option makes the most money. Though rarely said out loud, this hidden default underlies many of our choices. It’s the connective tissue that explains why college education and health care are so expensive, why the same politicians keep getting reelected, and on and on.

But this idea of financial maximization is built on another hidden default: that our rational self-interest is defined by what we need or want right now. We’re locked into a limited view of our rational self-interest. We care about only a limited subset of what we should actually care about. As a result, we routinely fail to see the full spectrum of values, ways of valuing, and perspectives worth evaluating when making decisions.

Our imagination for the present and the future is limited by the combination of these two hidden defaults.

Generocity: Community, and the idea of serving the needs of community by working with them not for them, is integral in the nonprofit/social impact sphere. Who do you see as your community?

Strickler: For a decade my community was Kickstarter and all the backers and creators around it. Those people defined my outlook and sense of responsibility. Since leaving the company my focus has been a mix of my close family (wife and child) and thinking deeply about the larger structures that we live within. How we come to believe the things we believe, how what’s normal gets defined as what’s normal.

In my writing, I’m exploring my own encounters with these questions (Why are there so many chains in my neighborhood? Why has real estate gone up in value but pay hasn’t? Why does consuming media make me feel bad about myself?) and trying to shine a light on them in a way that everyone can learn from.

In the book I also propose a new idea, called Bentoism, that I could see becoming a new kind of community I’ll be part of. But these are early days.

Create X Change: You’ve coined the term “Bentoism.” What is it?

Strickler: Bentoism is a framework that helps us better see our values and rational self-interest. While the world today is focused on the needs of Now Me, Bentoism says there are other perspectives that must be balanced: Now Us, Future Me, and Future Us.

Each of these dimensions — or Bentos, to use the metaphor — is a space of rational self-interest. My choices don’t just affect me right now, they affect my future self too. And my responsibilities and influences aren’t limited to myself, they affect the people around me, and vice versa. And my choices affect the world that the next generation will inherit.

"Values like community, fairness, and tradition should shape what gets decided and who does the deciding."

In each of these spaces there are values that rightfully guide how decisions should be made. For issues affecting Now Us, values like community, fairness, and tradition should shape what gets decided and who does the deciding. For issues affecting Future Us, space should be made for the considerations of the future generations who cannot be there to speak for themselves.

Generocity: Bento boxes are best known for three things: 1) the variety of tastes and textures of the food included; 2) the artfulness of their arrangement; 3) the small portions. Can you tell us how those find analogy in your construct of bentoism for business?

Strickler: Bentoism is a new way to think about our self-interest. It’s based on the idea of the bento box, which has been popular in Japan for a thousand years. “Bento” derives from a Japanese word meaning convenience. Because it has four compartments and a lid, the bento is a convenient way to carry a healthy and balanced meal.

It also honors the Japanese eating philosophy of “hara hachi bu,” which says the goal of a meal is to be 80% full. That way you’re still hungry for tomorrow.

Bentoism is a similar idea, but for our beliefs, goals, and desires. A way to see our full self-interest, and to make self-coherent decisions. Much more on this in the book, in the talk, and online in the weeks to come.

Project

ADVANCE by GenerocityTrending News