The founders of the Women’s Medical Fund never imagined it would still be around 35 years later

December 23, 2019

Category: Featured, Long, People, Q&A

December 23, 2019

Category: Featured, Long, People, Q&A

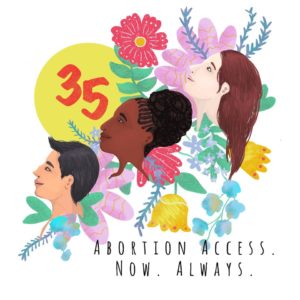

As the Women’s Medical Fund gets ready to turn 35, Generocity caught with executive director Elicia Gonzales to talk about the nonprofit that protects and expands abortion access for low-income people in the area.

Specifically, we wanted to know about the organization’s founding, and its plans for the next few years.

The following Q&A was lightly edited for style and clarity.

Generocity: Tell us about the founding of the Women’s Medical Fund.

Elicia Gonzales: In 1973, abortion was decriminalized in the United States. However, in 1977, the Hyde Amendment banned the use of federal Medicaid funds for abortion, thereby restricting access to this procedure for the thousands of people who utilized Medicaid coverage to pay for their health care needs. While some states opted to use state dollars, in 1985 the Pennsylvania legislature prohibited the use of state Medicaid funds for abortions, thereby creating an enormous disparity in access.

WMF has a long and rich history dating [unofficially] back to the early 1980s — when Barrie O’ Gorman, an Elizabeth Blackwell Health Center volunteer realized that although abortion was legal, it was out of reach for many of the women she counseled. O’Gorman set aside $250 of her own money to loan to women in need of abortion care. After an individual repaid the loan, O’Gorman could offer the loan to another woman.

The founders raised money through house parties, mailings, and telephone calls to friends.

Then in 1985, when the Pennsylvania Abortion Control Act was passed — essentially PA’s version of the Hyde Amendment — it prevented women from using Medicaid to pay for abortion care. As a result, reproductive rights activists Allyson Schwartz, Diane Kiddy, Liz Werthan, Anne Hearn, Richard Cohen, Frances Sheehan, and a few others formed the Greater Philadelphia Women’s Medical Fund (GPWMF). Much like today, government funding and corporate sponsorship was out of the question as a means of generating revenue, so the founders raised money through house parties, mailings, and telephone calls to friends.

In June 1989, the organization achieved official nonprofit status by becoming a unit of Resources for Human Development, and Shawn Towey was hired as the first official director.

By 1991, GPWMF had become the primary source for people seeking financial support to cover abortion care. Longtime executive director Susan Schewel was hired in 2003, and worked with the board to increase revenue, strengthen organizational infrastructure, hire additional staff, and change the name to Women’s Medical Fund.

During Susan’s tenure, the staff and board also expanded the organization’s vision of advocacy centered on racial and economic justice. I was hired as the successor to Schewel in July 2017 and am working with a passionate team of staff, board, volunteers, and donors to address the intersecting effects of reproductive, economic, and racial injustices related in the lives of those most affected by abortion bans.

In summary, WMF was founded by a group of health care workers and feminists who organized themselves to develop a plan that lived outside a state solution — knowing that pleading with the PA State legislature to overturn the PA Abortion Control Act was futile.

When I asked one of the founders, Liz Werthan, what it felt like to be a part of such a radical effort back in the 1980s, she replied “We thought it was temporary!”

When I asked one of the founders, Liz Werthan, what it felt like to be a part of such a radical effort back in the 1980s, she replied “We thought it was temporary!”

Come June 2020, 35 years after WMF was founded, we will have provided more than $5.3 million in financial assistance to almost 39,000 people in Southeastern PA (and a bit beyond) who have decided to terminate a pregnancy but could not afford the cost of an abortion.

While we are incredibly proud of this accomplishment, we are frustrated that we still have to be here because of the existing and increasing restrictions to abortion care.

Generocity: Did the first year go smoothly? Was there any regret or only excitement in its first days, weeks, months?

Gonzales: The founders were committed to ensuring abortion access and worked tirelessly to bring the vision to fruition.

WMF was established by people who were incredibly busy with their jobs, with many already working in the reproductive health field in some capacity. Creating the fund was a large undertaking of people who already had a lot on their plates. Not to mention that they were devising a solution while being emotionally distraught by the sheer injustice of the intensifying abortion restrictions.

As a result, people had to be real about what they could take on. Many of the founding board members were responsible for counseling the pregnant people who needed financial support to pay for their abortion. One of the founders recalls that she was so angry with Rep. Henry Hyde and the U.S. Congress for discriminating so terribly against poor people, she could not adequately provide the counseling.

In the beginning, there were many conversations about how it would all work — from fundraising, to counseling, to fighting to overturn the Hyde Amendment. Most, if not all folks, thought it was a stop-gap measure and that eventually the fund would not be needed.

Generocity: Are the founders of the organization still involved in it?

Gonzales: Many of WMF’s founders remain supporters of the organization to this day. Some of the original founders state that this issue is more important now than ever and understand that ensuring abortion access now and always is critical for a person to be able to lead a healthy and dignified life.

In 2020, we will celebrate our 35th anniversary and hope to document our work through an oral history project with founders and other people connected to reproductive health in the late 1970s/early 1980s.

Generocity: Imagine you’re talking to someone who is thinking of founding a reproductive rights nonprofit. What would you tell them are the pitfalls or rewards? Do you have a primer of suggestions?

Gonzales: One of the first questions I would have of someone wanting to start an abortion access organization is “Is this what the community is calling on you to do?”

Oftentimes, in the spirit of wanting to help people and reduce suffering, well-intended individuals develop solutions to social injustices. While this is commendable and undeniably helpful to many, it omits from the equation a key piece — honoring that people and communities know best what is needed and that folks most impacted by systemic oppression must be the drivers of change.

I would want to know that the organization would be created by and for communities who are the experts in their own lives. Neglecting to do so is a major pitfall and creates an unnecessary “us/them” divide between the provider and the community.

The rewards of this type of work is knowing that we are impacting not just a single individual, but their family and community for generations to come.

In our last fiscal year, of the 3,282 people who received financial support for their abortion and responded to our feedback survey:

- 87% said our funding and having an abortion helped them improve or maintain their financial situation.

- 82% agreed that having an abortion helped to secure employment.

- 63% said funding and having an abortion helped them care for their children.

- 55% said they were able to go to or graduate from college.

- 84% said funding and having an abortion improved their overall well-being.

Generocity: How has the organization evolved from the original vision?

Gonzales: The folks who founded our organization thought this would be temporary. How could they have known that abortions are even more inaccessible now than they were in 1985?

Since our founding, abortion has become much more restricted. In fact, 278 restrictions on abortion were enacted between 2013 and 2018 alone, including in PA.

We remain the largest abortion fund in the state (and country), helping more than 3,00 people each year access abortion care. Yet, we are still nowhere near meeting the need.

In our 2019 needs assessment, we estimated that in our catchment area alone, approximately 6,300 people rely on external financial support to pay for their abortion each year due to their inability to pay out of pocket or to use their Medicaid health coverage — and about 3,200 individuals are forced to carry their pregnancies to term because they are unable to afford the procedure.

This and other barriers to abortion place an inequitable burden on low-income women, especially women of color and teens. The current political climate brings with it more threats to low-income women’s access to contraception and abortion.

Funding abortions is only part of the solution to ensuring reproductive justice.

A 2015 Turnaway Study showed that those who were denied an abortion were three times less likely to be able to provide for the basic economic needs of their families than those who were able to get an abortion. Conversely, those who receive funding for an abortion through the WMF Help Line tell us how access to an abortion had a positive impact on their life.

Last year, 37% said it let them finish high school or get a GED, and 78% reported that it allowed them to find or maintain employment.

Funding abortions is critical to our work. We have always known, though, that funding abortions is only part of the solution to ensuring reproductive justice.

In 2015, the staff and board expanded the work to include community organizing. We trained several existing volunteers, mostly younger folks in their 20s and 30s, to learn about grassroots organizing and they became what is now called the Philadelphia Reproductive Freedom Collective (PRFC).

They created a campaign to shut down anti-abortion centers (AACs were formerly called “crisis pregnancy centers”). AACs use tax dollars to purposefully lie to pregnant people to dissuade them from having an abortion. A pregnant woman who was seeking all options counseling went to the AAC in Center City and was told she had a miscarriage so would not need an abortion. She found out weeks later she was still pregnant.

-

PRFC is designed to be a container for the cultivation of leadership of Black, Brown and Indigenous people of color (BIPOC) and is working alongside WMF to fight for abortion liberation.

We are intentionally using a grassroots organizing strategy and, like our founders, are working outside of a state solution — knowing that we cannot rely on our state government to grant us permission to be free. Building community power and funding abortions are essential components to ensuring reproductive justice.

Generocity: Where do you see the organization being in the next 5-10 years?

Gonzales: In 2020, we will create a new strategic plan for the next 3-5 years. We know that process will reveal a plan that calls on us to:

- Center the work on people most impacted by abortion restrictions. This can look like hiring and retaining more BIPOC staff who have experience of living in poverty or accessing an abortion fund; ensuring the board is comprised of a majority of BIPOC, and that PRFC is led by BIPOC individuals.

- Evolve into a multiethnic, inclusive and antiracist organization. This can mean establishing internal policies and procedures that promote justice and equity — including intentional focus on self-care and joy, creating infrastructure that allows for collective decision-making and power held by BIPOC, determining organizational and movement partners with whom we align, and deciding our stance on issues that intersect with abortion access (i.e. criminal justice reform), just to name a few.

- Change the name of the organization to something that is more inclusive of all genders — because not only people who identify as women get pregnant or need to access abortion care.

- Expand our catchment area outside of the current five counties (Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery, and Philadelphia). Consider all of the ways we can ensure access that include direct funding for abortion care, but also could include increasing education about self-managed care, for example.

- Expand the base of grassroots organizers who will join our fight to decriminalize abortion. This includes working alongside existing donors to determine how best to be in accompliceship with BIPOC in advancing our mission.

- We will become a household name — or at least more folks will know we are here, we have been here, and we will stay here as long as needed until abortions are free and accessible for anyone who needs one.

Trending News