Ronald Crawford believes Meek Mill, Jay Z and Nas have something healing to say to Philly’s returning citizens

February 14, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, People

February 14, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, People

Disclosures

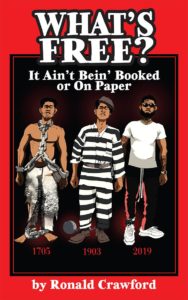

This guest post was written by Brandon Dorfman, a freelance writer whose work focuses on addiction, drugs, race and adoption issues.Ronald Crawford has a deep understanding of Meek Mill’s trauma, having chronicled the North Philly hip hop artist’s lost decade to a punitive cycle of probation and incarceration in a recent book What’s Free? It Ain’t Being Booked or On Paper.

The book also details Crawford’s work with hip hop therapy, and uses tracks such as Meek’s hit song “Trauma” to help returning citizens break free from the effects of incarceration. “A lot of times incarceration robs people of their most productive years, so that’s almost like being dead,” said Crawford, who, like Meek, is a North Philly native.

Mental health is Crawford’s lane. As a student of hip hop culture, he sees as much potential in the words of Jay Z and Nas as most do in Carl Jung and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. That belief is the backbone of HipHopPsychoEd, his free therapeutic town halls that give Black Philadelphians impacted by the prison system a safe space in which to address their trauma and receive culturally competent counseling.

Mental health is Crawford’s lane. As a student of hip hop culture, he sees as much potential in the words of Jay Z and Nas as most do in Carl Jung and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. That belief is the backbone of HipHopPsychoEd, his free therapeutic town halls that give Black Philadelphians impacted by the prison system a safe space in which to address their trauma and receive culturally competent counseling.

“If you have a problem [such as mass incarceration] that disproportionately affects people of color, you need therapeutic interventions specifically designed for that culture,” he said.

At the Cecil B. Moore Recreation Center on North 22nd Street, and later, as part of the Pan-African Studies Community Education Program on Temple University’s campus, men and women in attendance shared about depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Trauma permeated the rooms. It was emblazoned on Crawford’s black hoodie with the words “got trauma?” fashioned after the once-popular “got milk?” advertisements that launched during the crack-cocaine era.

What those in attendance shared helped to change the narrative. They spoke with conviction about the burgeoning opioid crisis in North Philly, and the city’s singular focus on middle-class white kids on Kensington Avenue.

The discussion moved to their time in prison, and the detrimental effects of life behind bars. Dreams of freedom, while they were incarcerated, have become daily nightmares of being returned to the system now that they’re free.

And when trauma seemingly overwhelmed them, Crawford filled the empty space with song.

“If Jay-Z and Meek Mill are talking about ‘I’ve experienced trauma,’ little Jamar who’s 12 years old and idolizes Jay-Z or Meek Mill, he might start talking about ‘I got trauma too,’” Crawford said. He defended against many popular critiques of the genre, noting that talk of violence and drugs in music is an expression of personal trauma.

It was Meek Mill’s “Trauma” that spoke loudest to those who had gathered at the rec center and at he university campus recently. “How many times you send me to jail to know that I won’t fail. Invisible shackles on the king, ’cause shit, I’m on bail,” Meek’s lyrics echoed through the spaces.

Although Crawford’ has a predilection for Meek Mill, Derrick Cain prefers Nas.

“Nas has a lot of songs where he talks about growing up, things that he’s seeing … how he dealt with things,” said Cain, the community engagement editor at Resolve Philly who was among those in attendance.

In 2005, the court sentenced Cain to a federally mandated 10 years on a drug charge. Like most justice-involved persons, the carceral system fueled by media-driven stereotypes only worked to compound issues of depression and anxiety. Cain’s work with organizations like MenzFit, a nonprofit that aids low-income men in finding proper attire for job interviews, is helping to change that narrative, along with much-needed therapy.

“It was important for me to have a Black female [therapist],” said Cain, who initially had trouble connecting with one before a colleague at work said: “Here’s somebody who can understand our upbringing.”

“If you’re talking to somebody who has no idea about that, it’s hard to get help because they can’t relate,” Cain added

Hip hop is central to Crawford’s story

At 57, Crawford is an alumnus of hip hop’s old school. He grew up when artists like Schoolly D were dropping beats about the Philadelphia gang, the Parkside Killas. Today, his playlist is expansive, with names like Jay Z, Phora, Joyner Lucas, and, of course, Meek Mill — which reflects not only his own trauma but the changing face of hip hop over the decades.

Hip hop — the music and the culture — is a central part of Crawford’s story. So are violence and trauma.

He was raised around 24th and Lehigh in the 1970s when street gangs were a way of life, and Mayor Frank Rizzo used his bully pulpit to stoke racial tensions. At home, Crawford’s father found that local unions, for which he was trained and certified, would only hire white workers. The elder Crawford took out his anger and frustration, both emotionally and physically, on Ronald’s mother .

So Crawford spent the 1980s “numbin’ out” — self-medicating with cocaine and crack-cocaine until he was 27 years old, right around the time Public Enemy released Fear of a Black Planet.

“I could have benefited from therapy,” recounted Crawford, who, following a stint in rehab, moved to University City to earn his master’s degree. “Did I get mental health treatment? No, because I couldn’t relate to any of the people, any of the counselors that I met.”

Negotiating sociocultural realities to reflect the common background of shared communities is no small matter. While Crawford’s personal struggles established within him the need for personal connection, the professional arena presented an opportunity for practical solutions.

During a stint as a GED instructor, when William Shakespeare and Mark Twain proved challenging, Crawford found that Jay Z and Nas turned things around. “Now they were interested in reading and learning because the topic was interesting to them,” he said.

That moment was the first beat in what ultimately became Crawford’s hit track — the HipHopPsychoEd model of culturally relevant therapy.

The evolution of hip hop therapy

Crawford’s work builds off the research of the late Dr. Edgar Tyson of Fordham University, who was the first person to explore the therapeutic potential of hip hop culture and coined the phrase “hip hop therapy.”

Tyson was a social worker in Miami-Dade county, working with abused and youth experiencing homelessness when he incorporated hip hop into his therapeutic model. After finding success, he proceeded with a formal study. He presented his first groundbreaking paper at the 30th Annual Conference of the National Association of Black Social Workers in 1998.

“[Dr. Tyson] finally put a name to it and introduced hip hop culture into a clinical setting,” said J.C. Hall, a licensed social worker from Long Island and former protégé of Tyson’s who continues to carry on his legacy.

Hall, who’s also a hip hop artist who goes by the name of Fienyx, listens to Meek Mill and was recently introduced to Roddy Ricch. He loves to hear Fabolous and Charlamagne tha God talk about trauma on The Breakfast Club. He’s an advocate for hip hop therapy groups and built a state-of-the-art recording studio at a high school in the South Bronx to help students connect. His efforts there were documented in the short film Mott Haven.

“You have to keep in mind, as a practitioner, that this is a culture,” said Hall, stressing that hip hop therapy is about connections. “It’s not just rap music.”

Traditionally it’s been a tough sell. Although Black Americans are 20 percent more likely to need mental health services than the U.S. population as a whole, only about 30 percent of them seek out treatment. That’s compared to around 43 percent of the U.S. population as a whole, per the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

The reasons for this are numerous, including socioeconomic factors, discrimination in healthcare settings, and a cultural taboo against therapy.

More importantly, statistics show that most counselors are white, making it difficult for Black Americans to open up and feel comfortable discussing shared experiences.

“It really goes back to the issue of trust,” said Dr. James Jones, Crawford’s mentor, and a frequent collaborator. “Anybody that has any mental health issues … [they’ve] experienced and done things that most of them might find embarrassing, shameful. A lot of times, we discuss those things, the people that we discuss with are very judgmental.”

The Black community wants treatment, he said, but centuries of institutional racism gives people pause and a reason to distrust mental health providers.

Jones’ musical tastes trend towards the old school. He grew up on Germantown Avenue, after moving from Newark, New Jersey as a young child following the race riots there in 1967.

He’s an African American forensic psychiatrist who has worked for 20 years at the Criminal Justice Center in Philadelphia, and whose personal traumas and story of childhood abuse have informed his practice. He wrote about this in his book I’m Alright: Overcoming Physical and Emotional Abuse Through Faith.

Others prefer to grapple with the criminal justice system and violence in more readily tangible ways — job training, housing initiatives, and gun buyback programs. With District Attorney Larry Krasner leading the charge for criminal justice reform in the city, and media figures like Solomon Jones initiating large-scale mentoring programs, Crawford and Jones often find themselves discussing their frustration that mental health isn’t part of the conversation.

“A lot of programs, they deal with things that sound right, things that are surface,” Jones said. “[But if you] really talk to people, there’s a lot of trauma.”

Becoming an activist for culturally relevant therapy

Ronald Crawfod believes one of the things missing from criminal justice reforms efforts is culturally relevant therapy to help people heal from the traumas of violence and incarceration. (Courtesy photo)

The need for culturally relevant therapy among returning citizens in the Black community and people of color has made Crawford an activist. He’s written two books on the topic, including Who’s the Best Rapper? Biggie, Jay-Z, or Nas, and the aforementioned “What’s Free?,” both of which he’s placed in the hands of every politician and pundit in the greater Philadelphia area.

That includes those at the Gun Violence: Beyond a Conversation seminar at Canaan Baptist Church in Germantown last November. With local pols like Rep. Dwight Evans, Krasner, and more in attendance, Crawford sat in the front row and listened intently about the need for criminal justice reform. “Lock ‘em up forever feels good,” said Philly’s progressive district attorney, “but it doesn’t work.”

When Crawford spoke, Krasner deferred to other panelists to respond to Crawford’s question about mental health.

Still, there are number of public figures who were willing to engage that day. Sen. Art Haywood shook Crawford’s hand and Det. G. Lamar Stewart, the assistant director of community engagement in the district attorney’s Office, spoke of the need for trauma-informed care specialists to help neighborhood youth. George Mosee, the executive director of the Philadelphia Anti-Gun/Anti-Violence Network, added that “Mentoring without resources is destined to fail.”

Where to go from here

“Violence is a learned behavior,” Crawford said. “And in order to change learned behaviors, you’ve got to change values.”

“That only happens in therapy,” he added “So why do we have problems such as violence, and criminal justice reform, that don’t have those types of initiatives? It’s beyond me.”

So Crawford will continue his work with HipHopPsychoEd and returning citizens in the city. He will continue to give young men a place to unload their fears about dying too young, and will help shoulder the burden of mothers whose sons were traumatized by the carceral system.

And he’ll play Meek Mill’s track “Traumatized” (not to be confused with the song “Trauma”) while he does so:

Cuz I was only a toddler, you left me traumatized, you made me man of the house and it was grindin’ time.

Trending News