This Juneteenth, let’s remember the U.S.C.T. and Camp William Penn

June 18, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

June 18, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

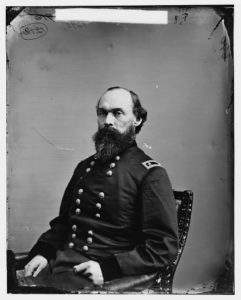

This article was originally published at The New Next on Medium. Photos used in this version of the article are from the Library of Congress Liljenquist Family Collection, Gladstone Collection and Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs.

In recent years a missing page from history has revealed that Philadelphia, long known as the nation’s Cradle of Liberty, is also the starting point for the nation’s oldest African American holiday.

Two years prior to Juneteenth — the oldest celebration commemorating the end of slavery in America — Philadelphia would be the city to host the first African in America Parade in the United States of America. This parade consisted of several hundred African Americans marching without arms or uniforms in file with drums, and inspiring banners as they headed for the first training camp for the United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.).

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, free Blacks and runaway slaves in the North rushed to sign-up with Union armies. Many were turned away, told it was a white man’s war. It was almost two years before African-American men got their chance to fight.

The formation of Camp William Penn dates from July 17, 1862, when Congress enacted a bill called The Militia Act authorizing the President “to employ as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary for the suppression of the rebellion, and for this purpose, he may organize and use them in such manner as he may judge best for the public welfare.”

Albumen print of Camp William Penn, Pennsylvania, photographed by B.F. Reimer of 615 & 617 North Second Street, Philadelphia, ca. 1863 to 1865. (Gladstone collection from the Library of Congress)

Camp William Penn has the unique distinction of being the only one set up exclusively to train Black troops drawing recruits from Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Jersey. The camp was located in La Mott near the present day site of the Cheltenham Mall in Montgomery County.

It was also the largest training facility of the 18 in the nation during the Civil War. Comprising over 10,000 men, 11 regiments of U.S. Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.) were trained there: the 3rd, 6th, 8th, 22nd, 24th, 25th, 32nd, 41st, 43rd, and 127th. Recruits first arrived on June 26, 1863. Many went on to fight in Virginia, South Carolina, Florida and elsewhere.

Other people of color who were not of African descent, such as Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Asian Americans also fought under U.S.C.T. regiments. Regiments, including infantry, cavalry, engineers, light artillery, and heavy artillery units, were recruited to U.S.C.T. from all states of the Union.

Approximately 175 regiments comprising more than 178,000 free Blacks and freedmen served during the last two years of the war. Their service bolstered the Union war effort at a critical time. By war’s end, the men of the U.S.C.T. made up nearly one-tenth of all Union troops. The U.S.C.T. suffered 2,751 combat casualties during the war, and 68,178 losses from all causes. Disease caused the most fatalities for all troops, both Black and white.

In actual numbers, African American soldiers eventually comprised 10% of the entire Union Army (United States Army). Losses among African Americans were high, in the last year and a half and from all reported casualties, approximately 20% of all African Americans enrolled in the military lost their lives during the Civil War. Notably, their mortality rate was significantly higher than white soldiers:

“[We] find, according to the revised official data, that of the slightly over two million troops in the United States Volunteers, over 316,000 died (from all causes), or 15.2%. Of the 67,000 Regular Army (white) troops, 8.6%, or not quite 6,000, died. Of the approximately 180,000 United States Colored Troops, however, over 36,000 died, or 20.5%. In other words, the mortality rate amongst the United States Colored Troops in the Civil War was thirty-five percent greater than that among other troops, notwithstanding the fact that the former were not enrolled until some eighteen months after the fighting began,” noted historian Herbert Aptheker.

U.S.C.T. regiments were led by white officers, while rank advancement was limited for Black soldiers. The Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments in Philadelphia opened the Free Military Academy for Applicants for the Command of Colored Troops at the end of 1863. For a time, Black soldiers received less pay than their white counterparts, but they and their supporters lobbied and eventually gained equal pay.

The courage displayed by colored troops during the Civil War played an important role in African Americans gaining new rights. Former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass’ sons were among the notable members of USCT regiments.

“Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship,” wrote Douglass.

Camp William Penn’s mission was to train Black soldiers to save the Union, free the enslaved and re-unite the families. This army of Black men would go on to help the Union win the Civil War by tracking down Confederate Army commander General Robert Lee and contributed to his surrender in Appomattox, Virginia.

Soldiers from the camp’s 22nd infantry located President Abraham Lincoln’s assassin and conspirators, and captured them on the Eastern shores of Maryland. After passage of the Emancipation Proclamation these soldiers went from state to state to free Blacks who were still enslaved.

It was U.S.C.T. that marched to the Alston Villa in Galveston Texas, and surrounded the Alston Villa on Juneteenth, or June 19, 1865. Union General Gordon Granger took charge of the state of Texas and informed the nation’s last remaining slaves of their freedom, almost two and a half years after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

Legend has it while standing on the balcony of Galveston’s Ashton Villa, Granger (and his regiment of 2,000 federal troops) read the contents of General Order №3: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.”

The camp was recognized for its vital importance to the Union’s war effort and distinct mission. Lincoln’s decision to encourage African American enlistment during the Civil War marked a great departure from prior administrations. About 180,000 African Americans served in the Union army and more than 15,000 joined the Union navy. The recruits trained at Camp William Penn served in the army. The camp was situated on land previously owned by the family of well-known Quaker abolitionist Lucretia Mott, who recalled that “the barracks make a show from our back window.”

The Civil War would end less than two years after Camp William Penn was established. Many of its recruits distinguished themselves in legendary battles and were decorated for their bravery and valor. The camp closed Aug 14, 1865.

Celebrations of Juneteenth began the following year and continue to this day. Ironically, as the holiday expanded across the nation, Philadelphia, like many other cities in the North, embraced the advances of the Civil Rights Movement and each generation saw less celebration of Juneteenth.

While Texans were the last to hear about their freedom, they have been a leader in the resurgence of Juneteenth celebrations. On January 1, 1980, Juneteenth became an official Texas state holiday through the efforts of Al Edwards, an African American state legislator, reports the website Juneteenth.com. The successful passage of this bill marked Juneteenth as the first emancipation celebration granted official state recognition.

Until his death in April 2020, Representative Edwards actively sought to spread the observance of Juneteenth across America.

[Editor’s note: On June 16, 2020, Mayor Jim Kenney announced that the City of Philadelphia had designated Juneteenth as an official City holiday, and that City offices would be closed in observation of the holiday on Friday, June 19.]

Trending News