On Juneteenth, and the difference between the law and good intentions

June 19, 2020

Category: Featured, Medium, Purpose

June 19, 2020

Category: Featured, Medium, Purpose

Disclosures

This guest column was written by Stephanie Renée, a former Philly talk radio host and the founder of the nonprofit arts education foundation, Soul Sanctuary.Here — in what is sure to be a long, hot summer — can be a real start for America to grapple with the lies that form the underpinning of its citizens’ understanding of freedom. And no better time to begin than with Juneteenth.

Paraphrasing an African proverb, “Only when lions tell their own stories will hunters cease to be heroes.” Through that lens, let’s examine Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, and the U.S. Constitution.

A quick timeline:

- Lincoln was elected on November 6, 1860.

- Less than a month later, South Carolina became the first of 11 states to ultimately secede from the United States to form the Confederacy.

- In March of 1861, Congress first proposed the addition of a 13th Amendment to the Constitution stating that “no amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.” This language upholds the principle that slave states could maintain business as usual, as far as Congress was concerned, indefinitely. This version was not ratified.

- Lincoln was inaugurated on March 4, 1861.

So, to recap: in response to Lincoln’s election, states began to opt out of being united, and were eager to maintain their slave economies, with Congressional blessing. But pushback kept this from being the law of the land. This is what Lincoln inherited on day one of his tenure.

Let’s proceed …

- On April 15, 1861, South Carolina fired on Fort Sumter, initiating the Civil War.

- By December of that year, Union war leaders were recommending that Lincoln emancipate slaves who had been abandoned by their former owners and enlist them to fight for the resistance, which Lincoln refused.

- Instead, by February 1862, the President had drafted a resolution to compensate former slaveholders for their emancipated “workers.”

- This went into effect in Washington, D.C. on April 16, 1862, a day now celebrated there as Emancipation Day.

So, under Lincoln’s direction, D.C. slaves were freed by a government subsidy program for their owners, while the actual war was still going on.

In the following months, other acts of Congress finally empowered the Union to enlist former slaves to assist in the fight for their own freedom, with a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation proposed on July 17.

But, in the middle of wartime, it was suggested to wait for a substantial Union victory to present it to the public. For the optics.

The wide-sweeping final version of the document was not presented and signed into law until January 1, 1863.

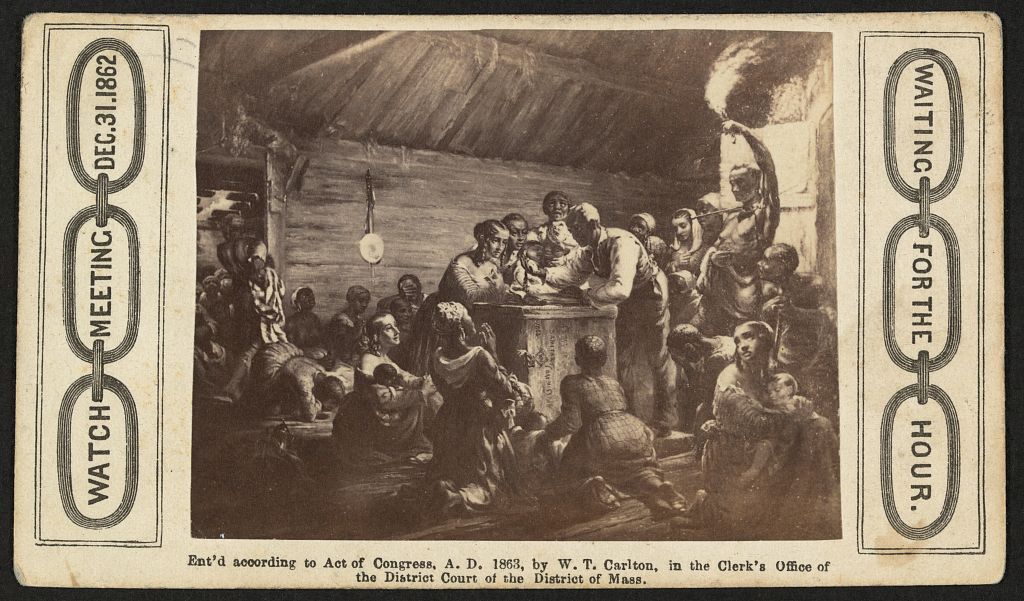

Watch meeting, Dec. 31, 1862–Waiting for the hour : Heard & Moseley, Cartes de Visite, 10 Tremont Row, Boston. (Library of Congress, public domain)

While the Emancipation Proclamation effectively ended legislative condoning of slavery in the States, it did not force the Confederacy to lay down their weapons or physically end their practices. Battles continued, and Lincoln had his own re-election to be concerned with.

The Senate proposed a 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in April 1864. The House didn’t pass it until January 1865. Then, it was sent to state governments for their ratification.

Some states were — shall we say — reluctant to do so.

On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, effectively ending the Civil War. Lincoln was assassinated less than a week later. It was on June 19 that Union soldiers landed at Galveston, Texas with news that the war had ended and the enslaved were now free.

Two-and-a-half years after Lincoln signed the Proclamation.

Two whole months after he had been killed.

The 13th Amendment became law on December 18, 1865, with the caveat that slavery was prohibited “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

Except for. An exception. A loophole.

So about Juneteenth …

Juneteenth isn’t about emancipation. It’s a symbolic commemoration, honoring venerable ancestors who suffered and bled for a far-off dream of freedom that has yet to be achieved.

And none of the little bit of freedom that we celebrate has been granted without extraordinary reluctance and resistance by white people in power.

Lincoln was no great emancipator, neither did Congress or the Proclamation effectively end anything: not the Civil War, not white privilege and entitlement, and certainly not slavery itself.

Black soldiers in Union uniforms ended the armed conflict, but the systemic and codified methods to undermine their “life, liberty and pursuit of happiness” remain firmly in place.

And in the 155 years since, we — their descendants — have never stopped fighting, because freedom has not yet been won.

I am the lion cub, roaring out my ancestors’ stories. Your hunters are no heroes, America.

Trending News