Drexel University’s Dr. Frank Lee projects civil dialogue seven stories tall for Philly Tech Week

October 6, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

October 6, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

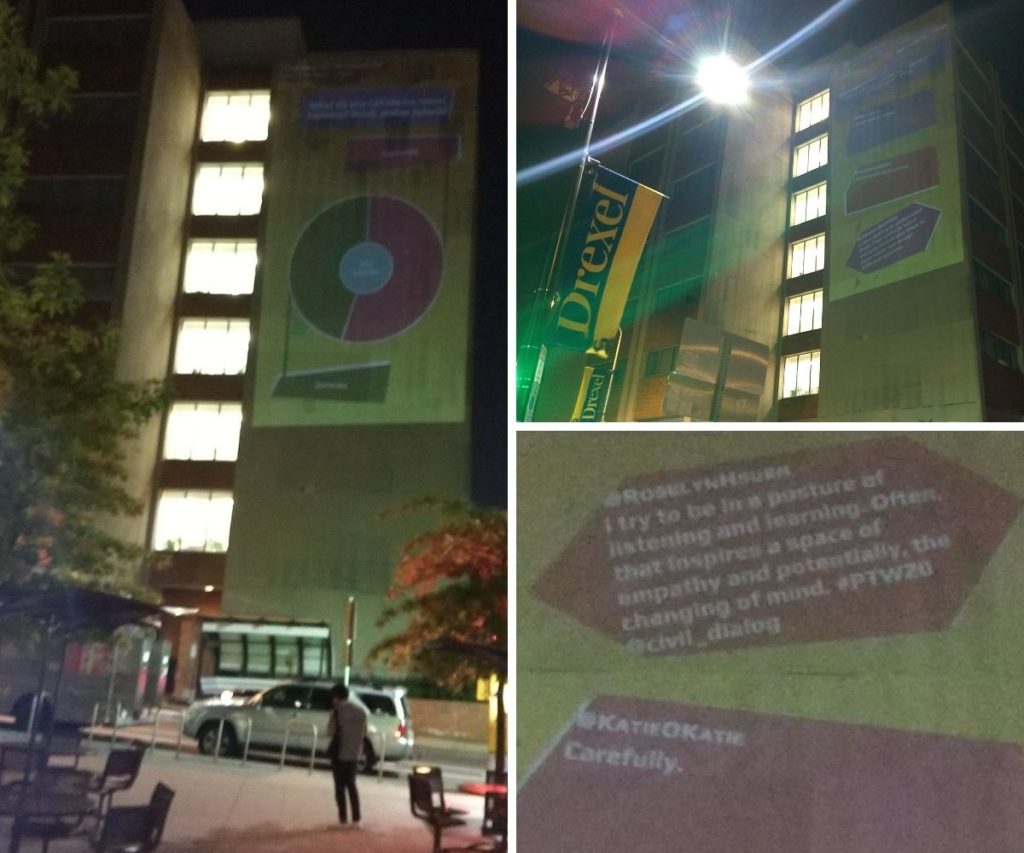

Dr. Frank Lee developed the Civil Dialogue program, a moderated Twitter feed projected seven stories tall on the side of Drexel University’s Nesbitt Hall to bring a modicum of humanity to the facade of social media.

His original vision saw 20,000 people packed together in a livestream read-and-response session that would bridge the gap between physical and online spaces. Physical interaction, he told Generocity, is a vital part of social interaction.

“I feel like I’m trying to recreate the sociability of video games as I experienced them when I grew up,” said Lee, explaining that he’s a product of the Golden Age of Arcade Games in the 1980s. It was an era when crowds gathered to watch, laugh, and even taunt others as they jockeyed for high score on now-classics such as Pac-Man and Asteroids.

“This is essentially the ’80s that I grew up in, that is missing with the multiplayer game online, because it’s all through verbal,” continued Lee, who made a name for himself projecting games like Pong and Tetris on the Cira Centre earlier in the decade. “There is a definite physicality to it that I want to sort of bring back that I felt.”

Social isolation is a central theme to much of Lee’s work, but social distancing has derailed much of everything in a post-pandemic world.

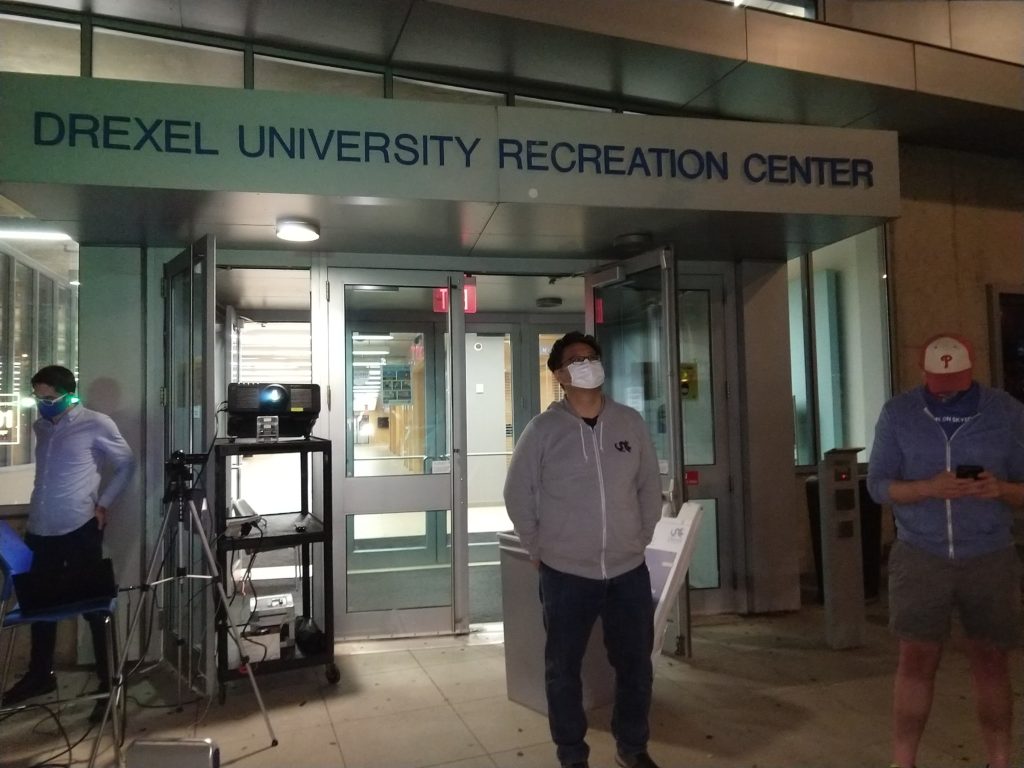

As has much of the world over the past eight months, Drexel University’s Lee and a local team from Gossamer Games reconfigured their moderated social media conversation Civil Dialog: Projecting Civil Messages to the World to accommodate the new COVID-19 landscape.

The event, a part of the 10th annual Philly Tech Week, supported by the Knight Foundation, and in partnership with Technical.ly, WHYY Radio Times, and Billy Penn, while still projected on a seven-story building, was held in the virtual arena, keeping in line with public health protocols.

Tweets projected onto Drexel University’s Nesbitt Hall on September 24 from 9 to 11 p.m. (Photos by Brandon Dorfman)

COVID-19 influenced Lee to shift how he thinks of his work, he said, forcing him to adapt a socially interactive project at the physical level. According to him, the presentation, which was originally scheduled for a conference in Washington D.C. in front of thousands of people, added a live streaming aspect to compensate for the novel coronavirus.

“My philosophy in my projects is do the best I can to prepare and then adapt to circumstances as they change,” he said, noting that he hopes to include more physicality to his work on the other side of the pandemic.

But for Lee, adaptation breeds success, leading him on a path of creative exploration and learning. He earned a bachelor’s degree in Cognitive Science from UC Berkeley and a doctorate. in Cognitive Psychology from Carnegie Mellon University before coming to Drexel in 2003 to teach Computer Science.

Ten years later, he followed his passion for gaming, becoming a professor of digital media at Drexel’s Westphal College. There, he founded the Entrepreneurial Game Studio, which teaches students how to design games and start their own gaming companies.

He said it was a “weird, roundabout” path that brought him where he is today, but it affords him the opportunity to do what he loves. The work he does explores the merger of the physical and digital worlds, using digital technology, internet, and augmented reality as he attempts to create more interesting interactions.

Lee wears a Philly Tech Week t-shirt marking the Guinness record-setting game of Tetris played on the Cira Center in 2014. (Photo by Brandon Dorfman,/em>

That’s how his game of Tetris on the Cira Centre in 2014 ended up in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s largest architectural videogame display. The previous world record holder was also Lee for his game of Pong on the same building the previous year.

According to Lee, Tetris is not only his favorite video game, but the most perfect one ever made. “You talk about your perfect games in baseball, the beautiful games in soccer, and so on Tetris is a perfect game in a sense that you have like five or six shapes that you rotate,” he marveled. “But it could create hours and hours of endless fun with just five different shapes.”

For all that video games have given to Lee, he makes sure to give back to the gaming community as well. Recently, he received funding from Intel Corporation to work with middle school students from the Baldwin School, Science Leadership Academy, and Upper Merion public school. The students worked on their own video game designs, all of which were showcased on the side of a building. As Lee explained, the effort was to help encourage more women and people of color to explore their options in the gaming industry.

“There has been an embarrassing lack of women and people of color in gaming,” Lee said. “And as a firm believer that in diversity there is strength, I have been passionate in my belief that more women and people of color in the game industry will only make our industry stronger and better.”

The truth is, Lee believes everyone deserves an opportunity to create their art, a term that was used in conjunction not only with video games but with the Civil Dialogue project too. Drexel graduates Chris McCole and Thomas Sharpe, the main programmer and director of Gossamer Games, respectively, referred to Civil Dialogue as an art installation. As they told Generocity, it’s a large-scale art piece that puts everyone’s voice into the public sphere in a physical way.

McCole and Sharpe, whose studio recently released their first game, Sole on Xbox and Steam, collaborated with Lee on the effort. As a moderated conversation, Civil Dialogue tweets would go through several filters before being projected on the side of Nesbitt Hall. Before the Gossamer Games team gave it a second go-through, a bot passed through everything first, looking for foul or derogatory language.

“We had some partners like Billy Penn, Radio Times,” said McCole. “Then we have those tweets, the IDs, and it pulls those up just through a bot when the application starts up, and it pulls down all the replies and sends it through different filters to search for bad language.”

Dr. Frank Lee watching the tweets projected on a building the night of Sept. 24, 2020. (Photo by Brandon Dorfman)

While Twitter may be a social platform, Lee noted, the common social framework can break in isolation. “I may just send off the first thing that comes up in my mind, which is usually the wrong thing,” he said, explaining that when people see each other face-to-face, there is a tendency to moderate what is said.

But through the efforts of Lee and the team at Gossamer Games, a more civil dialogue occurred on Twitter, at least for one evening. Although a few questions — such as “do you call them jimmies or sprinkles?” — did create tension, the evening, though quieter than initially planned, ended successfully.

“Hopefully, COVID is just a small blip that we need to get through and next year, we will do much more fun things together,” Lee said.

Project

Philly Tech WeekTrending News