A look inside the stubborn problem of access to benefits and relief in Kensington

December 8, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

December 8, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

Over the past few decades, reporters, academics, and feel-good philanthropic types swarmed the Kensington section of Philadelphia to write about, document, proselytize, and eulogize what they labeled a dying neighborhood, often from a distance and the distinct vantage point of privilege.

The most infamous of these efforts, the New York Times trauma porn tour de force from two years ago titled “Trapped by the ‘Walmart of Heroin,’” reduces a diverse and bustling region of proud, struggling people into an other to be gawked at from afar. Accordingly, in Kensington, alleyways are always dark, and each street is said to have a check-cashing store or bar — as if those descriptors don’t match any city on earth.

And people who use drugs are nothing more than addicts, reinforcing the stigma that substance use exists in a vacuum without humanity.

“It’s a struggling community, right, but it’s a proud community here, which I think a lot of the media hasn’t captured,” said Jose Benitez, executive director of Prevention Point Philadelphia, a Kensington-based public health and social services nonprofit that offers city residents a broad array of medical services utilizing a harm reduction-based approach. His organization established the city’s first needle exchange program back in 1992 and today lives by the motto “meet people where they’re at,” embracing no barrier treatment, which doesn’t require people to stop using drugs.

“[Kensington residents] are people who are proud to live here, people who have lived here for generations, but it’s also been a community that past administrations have neglected,” Benitez continued, noting that the area includes two of the poorest zip codes in Philadelphia. “It has a fair number of folks who are homeless here and a fair number of folks who have opioid use disorder.”

“It’s a really complex, mixed situation going on in Kensington,” he told Generocity.

Buried deep in the foundation of that complexity, at least in part, is the destruction of the welfare state and safety net benefits in Pennsylvania, the lack of which has led to increased poverty and homelessness in places like Kensington. Beginning with bipartisan efforts to reform welfare in 1996, signed into law by President Bill Clinton, up through local disputes over the General Assistance fund, what was once championed as an attempt to help low-income families soon became the cause of their struggles.

Today, Kensington residents are part of a larger block of Pennsylvanians that leave upwards of $450 million of federal funds on the table due to a system bled out and beaten down by politicians.

Like a snake swallowing its tail, welfare reform ensnared the neighborhood in a poverty causal paradox without beginning or end. De-industrialization and lost wages, epitomized for years in Kensington by the abandoned Schmidt’s Brewery, forced people to apply for government assistance, which, in turn, now required those in need to seek out non-existent employment opportunities — the so-called “welfare-to-work” program.

And then the city criminalized poverty.

As the Kensington Welfare Rights Union, an activist organization which has since evolved to the national stage as the Poor People’s Economic Human Rights Campaign noted years ago, when welfare reform led to a loss of hope and, by necessity, an increase in crime, drug use, sex work, and other illegal activities, the city didn’t send help to the area. Officials sent the police.

In 2001, under Mayor John Street and Police Commissioner John F. Timoney, Philadelphia sent an army into Kensington, including mobile command centers at several corners and hundreds of uniformed police officers. Officially part of the mayor’s then anti-blight initiative, KWRU advocates at the time reported that the invasion known as “Operation Sunrise” was a response to the failures of welfare reform. Why look at the root causes of poverty, the group asked, when it can so easily be criminalized?

Almost 20 years later, anti-poverty advocate and KWRU and PPEHRC co-founder Cheri Honkala continues to ask why the city hasn’t still hasn’t done anything substantial to solve the problem.

“I’d really like to know where all this money is for all these services,” said Honkala, a longtime Kensington resident who entered the political stage in 2012 as Jill Stein’s vice-presidential running mate. “If I was in charge, I’d be out on Kensington and Allegheny when people are going through withdrawal asking them if they wanted to go and get long-term hospital detox and into a recovery program. But that doesn’t happen.”

Instead, Honkala sees reporters, academics, and feel-good philanthropic types swarming the neighborhood, more often than not with a camera in hand.

“A lot of people come out with sandwiches and food and they pass it out,” she continued. “I think some of that stuff is more about making themselves feel better than really addressing some of the issues that the neighborhood faces.”

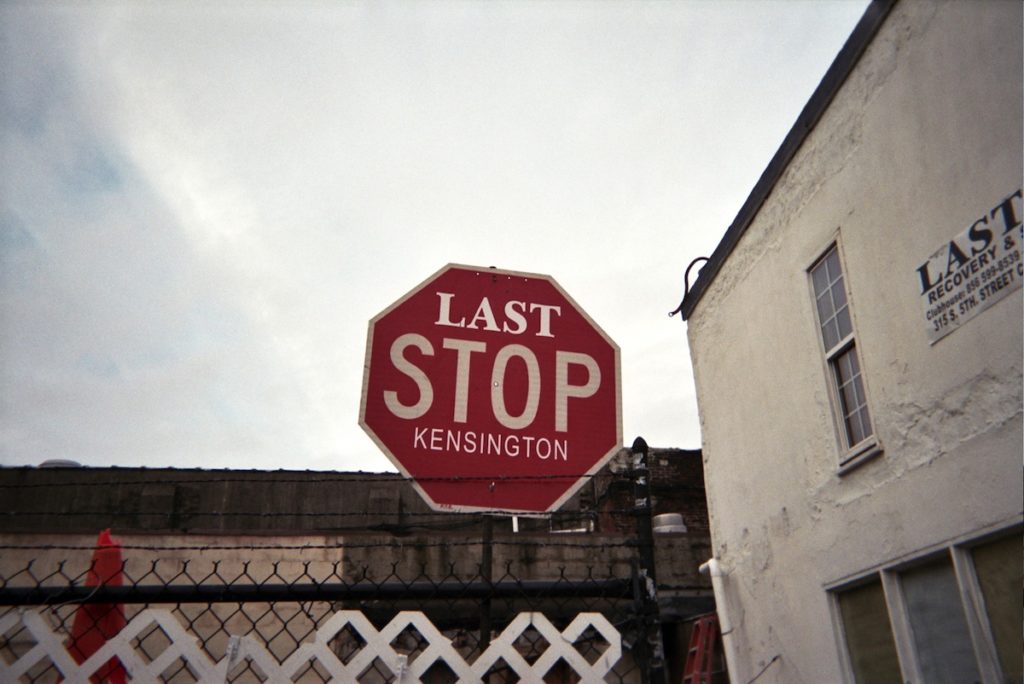

A look inside Kensington

A sign opposing a proposed bill that would have razed the Cesar Andreu Iglesias Community Garden in Kensington to make way for a 15-story apartment building and 54 sites to be developed into duplexes. In what was called a “win against gentrification” community members opposed the bill and the development plan was scrapped in September of this year. (Photo by Emily Rizzo)

In 1981, the New York Times reported on a disturbing trend in Philadelphia — the continued loss of manufacturing jobs throughout the metropolitan area.

Over the 10 years prior, several major companies either closed shop or moved south, including well-known businesses such as ESB-Exide, Philco Ford, Cuneo Eastern Press, Midvale Heppenstall Steel, and Bayuk Cigar. The job losses caused the region’s overall population to decline while making it one of only four cities to see a decrease in its African American population at the time.

Still, city officials were hopeful, noted the Times.

”The economic profile of the city as a whole indicates to me we have bottomed out and are experiencing a slight upturn,” said Philadelphia’s Director of Commerce Richard A. Doran, according to the New York Times in 1981.

Six years later, Schmidt’s Brewery, one of Kensington’s most prominent employers, would shutter its doors forever, taking with it 1,400 jobs. Today, the skeletal remains of the once-proud manufacturing plant that produced 3.15 million barrels of brew per year live on as a chateau of excess, a mixed-use gentrifiers paradise that includes retail, apartment, and performance space known as The Piazza at Schmidt’s.

“[Kensington] is a neighborhood that’s been very neglected and gentrified,” Honkala told Generocity. “I think that there’s a direct correlation between the redlining and discrimination against people of color in regards to both businesses and housing and employment. And so, in the last couple of years, I’ve really watched luxury units being built in front of my face and large numbers of visible, either homeless people or people that have serious opiate addictions, not get their needs addressed.”

According to a brief put together by Drexel University’s Urban Health Collaborative last year, the average annual income in Kensington is $12,669, making it the most impoverished neighborhood in the poorest big city in the nation. The area, which is a mix of Latinx and white communities, with a small African American population, has a poverty rate above 40% and an average life expectancy that’s five years less than the rest of the city. Almost 50% of households report their primary language spoken at home is not English.

The neighborhood also includes a significant unsheltered population. In 2018, Philadelphia counted 1,020 people experiencing homelessness citywide, with over half that number residing in Kensington. Outreach workers found that many in the unsheltered population are people who use drugs coming together for safety reasons amid a fentanyl crisis, something that is now more difficult during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Benitez.

And while some areas of Kensington have property crime rates that are much higher than other areas of the city, many parts of the region are, on average, much safer than the rest of Philadelphia. As per Drexel’s report, due to close social connections, residents in the neighborhood note they feel as safe going out during the day as those who live in Society Hill or the places in Northeast Philly that the cops call home.

As Councilmember María Quiñones-Sánchez, who represents Kensington in the 7th District, told Generocity, the neighborhood is a complicated place, due in no small part to it being an industrial corridor without the jobs to match, but it’s full of potential.

"If the 7th (District) does better the city does better."

“I love the character of neighborhoods in the city of Philadelphia,” said Quiñones-Sánchez. “As someone who has one of the most challenging districts, I’ve always said to my colleagues… one of the things that I’m most proud of is that every opportunity I can to illuminate how, if the 7th does better the city does better, is important.”

The drive to highlight her district is why the councilmember spent the past year working, in earnest, as co-chair of the city’s Poverty Action Committee. Along with scores of local stakeholders and hundreds of subject matter experts, Quiñones-Sánchez and the rest of her legislative colleagues laid out a roadmap to lift Philadelphia out of poverty. Together, they formed a public-private partnership with the United Way and developed an essential set of goals around education, housing, jobs, and the social safety net.

“I think that what we want to make sure is that people don’t look at this as us creating another bureaucracy or a bunch of other structures,” Quiñones-Sánchez said. “It really is about building capacity and for me it’s not building institutional capacity as much as people capacity in neighborhoods.”

A look inside welfare reform

In the summer of 2019, Pennsylvania Lt. Gov. John Fetterman took to the state senate floor attempting to save a Depression-era program known as General Assistance that paid poor and disabled people who were unable to work $200 a month.

The plan, which was done away with in 2012 but reinstituted seven years later by court order, was put on the chopping block by state Republicans once again. According to newspaper reports at the time, the floor debate turned into a “bare-knuckled” brawl of procedural tactics and name-calling not seen in a legislative body since Rep. Preston Brooks beat Sen. Charles Sumner half-to-death with his cane on the U.S. Senate floor in 1856.

When it was over, Fetterman lost the debate, and low-income Pennsylvanians lost what meager cash assistance the state had to offer.

“We started to see an increase in the number of homeless folks in the area when our state legislature decided that it would dissolve the General Assistance category of welfare,” said Benitez. “Even though it wasn’t a lot of money, what people did when we did have a General Assistance category of welfare was pool money together to sort of share rooms.”

“Just focusing on Kensington,” he continued, “we started to see a uptake in the number of people who are living on the streets.”

Cash assistance is always one of those programs that politicians on both sides of the aisle are willing to throw to the wayside, even though putting money into people’s pockets is one of the most beneficial ways to lift them out of poverty.

Almost 100 years ago, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt shepherded in the first cash payment program for needy families, Aid to Dependent Children. Architects of the initiative designed it exclusively for single mothers who were widowed, almost always to the exclusion of Black women and people of color.

But, in the 1960s and 1970s, welfare rights groups worked to expand the rolls, encouraging people of all racial backgrounds to apply who needed the help. A new demographic of cash assistance recipients, combined with a program that made it economically feasible to remain out of work by design, gave birth to a new American myth — Ronald Reagan’s “Welfare Queen.”

“We need to recognize the historic racial inequities in health, in wealth and education, in employment patterns,” said Trooper Sanders, CEO of Benefits Data Trust, a nonprofit that uses data and technology to help people access the social safety net.

“It’s important to ensure that everyone gets benefits that they need but the impact of a system that makes it difficult for people to do it on their own is going to be felt even more in communities of color,” he said, “and it’s going to exacerbate some of the inequities.”

Those racial inequities are what led to Bill Clinton’s now-infamous Welfare Reform Act of 1996, along with the continued disparagement of the social safety net to this day — and the dissolution of the nation’s cash assistance program. In its place, Congress bestowed upon the American public the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families block grant, an initiative which Philadelphia’s Community Legal Services notes rewarded government officials for reducing caseloads.

TANF is difficult by design, with rules and regulations that discourage applications and force people off the rolls as quickly as possible.

As statistics show, over the past couple of decades, while programs like Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), colloquially known as food stamps continue to grow in Pennsylvania, the number of families on the TANF rolls is in steady decline —falling from almost 500,000 in 1996 to just over 150,000 in 2016.

According to a Community Legal Services report, only 35 out of every 100 needy families receive TANF benefits in Pennsylvania. On top of that, at least 35,000 families who collect SNAP benefits qualify for TANF but don’t receive it.

Even if they did, the amount they would receive is a pittance.

“The benefit hasn’t been raised since it was called AFDC back in 1990,” said Maria Pulzetti, an attorney with Community Legal Services’ Health and Independence Unit. Her organization serves around 12,000 low-income Philadelphians every year, helping them navigate the social safety net.

“A family of three that receives TANF benefits in Pennsylvania is forced to live on $403 a month, which is about 22 percent of the federal poverty line,” she continued.

TANF is difficult by design, with rules and regulations that discourage applications and force people off the rolls as quickly as possible. Recipients must participate in work requirements for 20 to 30 hours per week, pursue child support against an absentee spouse, and submit three job applications per week while waiting to qualify. The program itself has a five-year strict time limit.

Initially hailed as a success by many, TANF has come to be seen for what it is by many — an abject failure.

A look inside the new Great Depression

Abandoned buildings lining Kensington Avenue near East Monmouth Street in 2019. (Photo by Erin Blewett for Kensington Voice)

A recent report in the Kensington Voice, the community newspaper founded by local reporter and Temple University professor Jillian Bauer-Reese, almost 60% of Kensington residents voted in this year’s presidential election, increasing from the matchup four years ago in which Hillary Clinton lost.

Like most of the city, an overwhelming number of residents cast their ballot for Joe Biden — upwards of 70% voted for the president-elect — although a fair share of the neighborhood threw their support towards the begrudgingly outgoing President Donald Trump. In total, wards 7, 19, 25, 31, 33, and 45 notched over 46,000 votes, a record turnout in a record election year.

The issues that keep most Kensington residents awake at night are no different from those that give the rest of Philadelphia insomnia. For Prevention Point’s Benitez, it’s fentanyl and the overdose crisis. Honkala worries about housing.

"I feel like I'm literally living in the Great Depression."

“I have over 30 families that are in abandoned properties in Philadelphia because there’s no place for them to go,” said Honkala, who, after 30 years of fighting for housing and performing takeovers, finally received a home of her own. “I just came from being with another homeless family about 10 minutes ago.”

“I feel like I’m literally living in the Great Depression,” she continued.

Much of that feeling Honkala attributes to the destruction of the welfare state and the rise of the gig economy. As she told Generocity, the evolution of technology not only took away jobs from the neighborhood but led to the collapse of entrepreneurship and small businesses too. For example, she said, local restaurants can’t compete in a day and age when customers expect everything to be delivered by the touch of an app.

She noted the people who supported the dissolution of the social safety net now realize just how important it was.

“I just put somebody in a takeover house today that works at UPS,” said Honkala. “It’s the classic thing that when they decided to dismantle our social safety net people weren’t looking at the fact that science is not going to go backwards.”

Benitez rode up the snake’s tail a little farther, discussing how job losses and the broken safety net led to an ongoing overdose crisis in Kensington. As he told Generocity, the part of the story that most people know is how companies like Purdue Pharma flooded the country with prescription opioids, beginning in the 1990s when doctors were taught to see pain as a meaningful vital sign.

What’s often ignored is the Drug Enforcement Agency’s crackdown on the industry, which forced doctors to cut off medications and sent patients to the streets to seek out alternative sources.

Opioids in pill form run about $36 in Kensington, versus $5 for a bag of heroin. In a down economy, it’s an easy decision.

“On top of that fentanyl comes in and fentanyl has this big influence in the illicit drug use market,” said Benitez. “It’s not something that people who mix the drugs do well all the time, and so it’s particularly a potent drug. And what tends to happen is you have this uptake in people overdosing.”

In addition to the overdose crisis, the introduction of fentanyl caused a whole slew of new problems for people who use drugs.

According to Benitez, as potent as it is, the high is short-lived. Users who would inject heroin two or three times a day were now injecting fentanyl 10 or 12 times a day, which causes wounds, abscesses, and other life-threatening medical issues — public health problems that groups like Prevention Point “licked” just a few years ago, Benitez noted.

At the intersection of all of these issues lie the problems of racial inequality and the coronavirus pandemic.

The pandemic predominantly affects Black and brown communities in Philadelphia, and while housing, joblessness, and the overdose crisis have become the media darling worries of the “economic anxiety” crowd in white America, both Benitez and Honkala note they are already happening and on the rise among people of color in Kensington.

But Honkala said, “the reality is that the majority of the people that are actually living on the so-called dole in this country are caucasian. People are getting a hard wake up now because of some of their backward thinking.”

“They didn’t fight like hell for a safety net that they so desperately needed themselves,” she added.

A look inside philanthropic solutions

As the calendar turned to December, with coronavirus cases continuing to rise and the cold weather beginning to settle in, Pennsylvania’s Department of Labor and Industry Secretary Jerry Oleksiak urged Congress to extend pandemic benefits to all Americans.

Set to expire at the end of the month, Mitch McConnell’s Republican-led Senate and Nancy Pelosi’s Democratic House were miles apart from where they needed to be on a deal. According to most recent reports, Democrats were set to give in on Republican’s biggest asks, abandoning another round of stimulus checks and allowing businesses to shield themselves from claims of negligence regarding COVID-19.

Throughout it all, the outgoing president has spent his time ignoring the looming deadline, choosing instead to spend his time frivolously disputing the results of last month’s election.

“I’m very concerned if unemployment doesn’t get extended after December 26,” said Honkala, who told Generocity that these days everyone, everywhere, is hungry. “I mean, that’s literally one of the things we do from early morning till late at night is we’ve got people that no longer are working and probably will compete with the other millions of people that are on unemployment right now to try and find a job.”

“The number one thing we’re doing is we’re feeding people and just housing anybody that comes in our direction,” she stressed.

But while COVID-19 makes its way through the city, several philanthropic organizations continued to boost the public safety net, buoyed by the city’s BenePhilly program, which still enrolls residents into public assistance programs via remote services throughout the pandemic.

The system is a lifeline to Philadelphia, especially during the coronavirus crisis, said Community Legal Services’ Pulzetti.

“We know there are a lot of barriers to benefits access which — during COVID includes the fact that the county assistance offices are closed to the public,” explained Pulzetti. “So people need to be able to apply either online or by telephone. That’s a barrier for people, although BenePhilly is certainly… a considerable asset to the city and helping people apply for benefits.”

Buttressing the need for a stronger social safety net are Benefits Data Trust and Campaign for Working Families, the former of which helps families in the city access an estimated $450 million in federal assistance that goes unclaimed every year. At the same time, the latter is a critical in helping to put money directly in low-income families’ pockets. CWF is a grassroots nonprofit that provides free tax preparation services that help those living in poverty take advantage of the Earned Income Tax Credit.

Graham O'Neill told Generocity that the EITC is the single most powerful anti-poverty program here in America.

Graham O’Neill, the Director of Partnerships at CWF, told Generocity that the EITC is the single most powerful anti-poverty program here in America. According to him, it can provide a family upwards of $6000 per year, an amount of money which can be transformative for people earning only $20,000 to $30,000 annually.

O’Neill explained that clients at CWF use that money to carry themselves throughout the year.

“Whether that be clothes, rent, heat, all the essentials of life are really helped by making sure that [our clients] are connected to that Earned Income Tax Credit,” said O’Neill. “Also, the child tax credit is another one that really helps out our clients.”

The problem is that not everyone who qualifies participates in these programs.

O’Neill said that nationally, only 80% of people “take a break,” which is why CWF works with Philadelphia’s You Earned It Philly campaign to make sure more people are aware of the benefit.

As for the future of benefits programs in Kensington and Philadelphia as a whole, philanthropic and community organizations can only go so far. A Band-Aid only works if it has a solid foundation. What low-income and unsheltered persons need in this neighborhood are new jobs, money in their pockets, people-centric benefits programs that address their specific needs.

Benefits Data Trust’s Sanders said that the latest technological advances are made with the end-user in mind. The social safety net needs to adopt that model.

"Let's just make this more centered on the individual."

“Over the decades as we’ve created these benefits programs we’ve put rules and regulations and being terrified of what could go wrong at the center of building these programs, and the person has been the afterthought,” said Sanders.

“But if we flipped it and put the person at the center and think about the person who needs help buying a bag of groceries — what’s going on in their life? How much time do they have to process things? What do we know about them already? What are the things to make their life easier to connect them to benefit so that they can go on about their life?” he asked.

“Let’s just make this more centered on the individual.”

Project

Poverty Action seriesTrending News