Where has the coronavirus relief money gone?

December 14, 2020

Category: Featured, Funding, Long

December 14, 2020

Category: Featured, Funding, Long

We are in a third surge of the pandemic. The health and economic chaos it has produced has ravaged the budgets of local and state governments.

Yet seven local counties that received a total of $810 million this March to help with the escalating costs had spent little more than one out of every five dollars received as of the end of August, the latest data available.

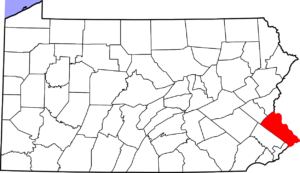

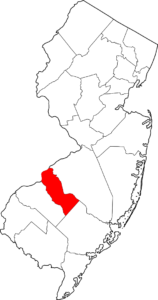

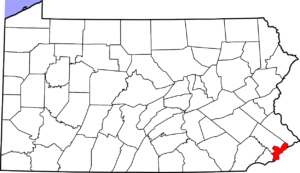

This according to spending reports filed with the U.S. Treasury office which is tasked with monitoring spending from the $150 billion Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF). CRF money was distributed directly to 119 counties across the country with populations over 500,000 people. Philadelphia, Montgomery, Delaware, Chester, Bucks, and in South Jersey, Camden County, were all CRF recipients.

The CARES Act dictates how CRF money is to be spent and the most significant restriction is it cannot replace lost tax revenue.

According to a National Governors Association survey, most entities were spending on health-related activities including COVID-19 testing and PPE, as well as economic relief. For several local counties, helping small businesses, especially those not eligible for the paycheck protection program, and education were major concerns.

A mandated interim report from the Treasury Department that covered the spending from March through June using data updated to the end of August, showed that Philadelphia, which has the highest percentage of positive COVID cases and highest rate of unemployment, had already spent 42% of its allocation.

The six other counties, however, had spent significantly less. Chester County reported spending one-third of its grant amount and Delaware County reported spending 25%. On the lower end, Camden County had spent 6.4%, Montgomery County had spent 3.3% of its allotment, and Bucks County reported spending only one-tenth of 1% of its share.

Counties nationwide are lobbying for additional time to spend the current CRF dollars they hav,e while also calling for additional federal funding and increased funding flexibility to cope with the pandemic. Republican legislators are using the interim reports as proof that no more money is needed.

“Before Congress spends even more money it doesn’t actually have, states and counties should allocate their existing allotments so we can thoughtfully determine what needs remain,” Sen. Pat Toomey (R., PA) told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

But groups such as the National Governor’s Association said seven out of 10 CRF recipients say changing and unclear guidance from the Treasury Department has slowed the allocation process.

Montgomery County congresswoman Madeleine Dean, a Democrat from Montgomery County, has cosponsored legislation to extend by a year the deadline to spend COVID-19 relief funds and allow nonprofit and emergency service organizations to use funds to replace lost, delayed, or decreased revenues as a result of the pandemic which is currently prohibited.

“It’s important that we extend the deadline for the Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) through December 31, 2021 and allow emergency services — like Volunteer Fire Departments — to access these relief funds,” Dean said. “It’s not only the right thing to do, it’s economically smart and allows our emergency services to continue to serve the people.”

How exactly have our local counties been spending their CRF dollars?

The Generocity TRACE project has compiled information from the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee (PRAC) , a federally mandated CARES Act oversight committee, and the Treasury Department’s Interim Cost Incurred reports which was revised up to August 24.

Treasury CRF Guidance (updated June 30, 2020) clarified that that for a cost to be considered to have been incurred, performance or delivery must occur during the covered period but payment of funds need not be made during that time (though it is generally expected that this will take place within 90 days of a cost being incurred). Cost incurred then means the services were provided but payment has not necessarily been made.

The COVID testing information was compiled from Pennsylvania Department of Health and Covid Act Now. Unemployment data is of October 2020.

Bucks County

CRF Allocation: $109,628,270.10

Cost Incurred: $147,226

Positive Test Rate: 17.7%

Unemployment Rate: 6.3%

When the CRF was announced, a Bucks County spokesman said that the county was awaiting guidance from the Federal government to determine how to spend the money. According to its U.S. Treasury interim report, by June 30th Bucks County had only spent 1/10 of 1% of its $110 million allotment, by far the slowest spending of any of the regional counties.

By December, The Bucks County Courier reported that the county’s CRF spending had grown and included $3.8 million to the county’s tourism promotion agency; $542,329 for an envelope sorter for the mail-in ballots; $420,000 for Bucks County Community College and $132,341 for audio/visual equipment for the county commissioner online meetings.

One of Bucks County’s first announced spending objectives was to help small businesses and nonprofits get on their feet by setting aside $6 million for loans of up to $25,000 or 25% of operating expenses for companies with fewer than 50 fulltime employees. According to the Bucks County Redevelopment Authority website the application window for the Bucks Back to Work Small Business and Nonprofit Grant Program is now closed.

Camden County, NJ

CRF Allocation: $88,375,283.10

Cost Incurred: $5,623,169

Positive Test Rate: 12.9%

Unemployment Rate: 7.9%

By June 30th, Camden County had spent 6.5 percent of its allotment, but in July, the county announced its CRF spending plan — $3.2 million in municipal aid; $28.7 million to reimburse hospitals; $16.5 million going to county operations; $4.8 million for county agencies; and $21.5 million for a small business grant program.

PRAC reports showed that the largest recipient of Camden’s CRF was Solix, Inc., a public sector program management firm, which received $20 million to manage and disperse funds for the small business grants program. Nonprofits and small businesses with revenues under $5 million and 25 employees or fewer, may qualify for a grant for up to $10,000. In addition, Cooper University Health Care and Kennedy Hospital received $14 million and $2.2 million respectively.

Camden County also pushed money to its townships and boroughs the largest amounts were $400,000 to Cherry Hill, $360,000 to Gloucester and $350,000 to Collingswood townships.

Chester County

CRF Allocation: $91,606,532.10

Cost Incurred: $30,649,993

Positive Test Rate: 11.4%

Unemployment Rate: 4.8%

One of the largest of Chester County’s expenditures was for $20 million, about 22% of its CFR allocation, for COVID-19 blood tests that ultimately failed. Already $13 million has been paid to Adviate Inc., a Malvern based-company in a no-bid contract to provide one million COVID-19 blood tests. After getting $2 million worth of the test kits, the county told Adviate to stop delivery.

In April, Chester County Commissioners’ Chair Marian Moskowitz said, “We chose to work with Advaite because our evaluations showed that the company’s test kits performed most efficiently and accurately. The fact that Advaite is part of the Chester County business community is a real bonus.” Advaite claimed the blood test was 97% accurate for certain antibodies and started providing the Chester County Health Department with thousands of the $20 blood test kits.

In September the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the testing program was “quietly shelved” over gross inaccuracies about the test. By then the county had already given Advaite $13 million.

In October, the Chester County Commission announced additional CRF spending including $3.5 million to help Chester County nonprofits, $28 million for childcare and $10 million for Chester County public schools.

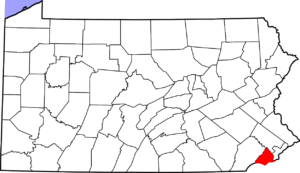

Delaware County

CRF Allocation: $98,892,981.10

Cost Incurred: $25,334,015

Positive Test Rate: 13.2%

Unemployment Rate: 7.1%

Delaware County is allocating $45 million to recoup COVID related personnel costs — its top spending area. This was followed by education. The Delaware County Council at its September meeting allocated $20 million to the Delaware County Intermediate Unit (DCIU) to provide support to the 15 public school districts throughout the county. According to the PRAC’s tracker, the DCIU had not spent down the funding during the interim report period.

An additional $17.3 million was used to create the Delco Strong Program — a grant program for small businesses and nonprofits. In November, Delaware County reported it was still debating what to do with $42 million, but by last week, a spokesperson for Delaware County said all the funds, except $5 million, had been allocated.

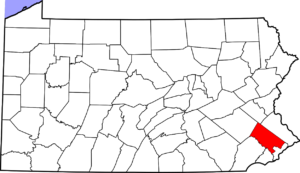

Montgomery County

CRF Allocation: $144,988,260.10

Cost Incurred: $4,749,500

Positive Test Rate: 12.1%

Unemployment Rate: 5.8%

Education was also a top area of CRF spending for Montgomery County. While the interim report is showing that only $5 million of the $145 million has been incurred, the PRAC tracker shows that the county gave $15 million to the Montgomery County Intermediate Unit 23 .

Another $15 million was given to the Redevelopment Authority of Montgomery County, of which they have spent $10 million, most of it for the Montco Cares Program to provide childcare financial support directly to families from October 5 through December 30, 2020.

Philadelphia County

CRF Allocation: $276,406,952.60

Cost Incurred: $115,826,450

Positive Test Rate: 14.8%

Unemployment Rate: 10.6%

Rental assistance and small business support were top concerns for the Kenney administration. This latest allocation of funds brings the City’s direct support for small business assistance to $38.7 million. and for rent relief to $39.4 million.

Philadelphia’s CRF portion represents about 44% of coronavirus-related money the city has received.

While the City’s CRF share was the second largest in the state, the City received less than 6% of the state’s CRF funding, despite having more than 21% of the state’s COVID-19 cases.

Project

TRACETrending News