Community organizations lament COVID-19’s effect on Philly’s key anti-gun violence initiative

May 13, 2021

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

May 13, 2021

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

In a lull between the spring and autumn waves of the pandemic, racial tensions widened in Philadelphia, with violence and protests consuming the city.

Like so many across the country, residents in the area’s Black communities bore witness or, in several cases, fell victim to white power structures. Despite the sleeping virus, they took to the streets to make their voices heard.

Tensions came to a head in July of 1918 when an angry mob of Irish men and women in the Grays Ferry section of South Philadelphia surrounded the home of Adella Bond, an African American woman working as a municipal court probation officer for the city. As the region began to integrate during what scholars would later call the Great Migration, acts of racial violence began to intensify. Earlier that summer, white mobs greeted one Black family by harassing them and burning their furniture; white agitators stoned Bond only days before the crowd appeared at her house.

On a Friday in late July, 23-year-old Joseph Kelly stood outside 2936 Ellsworth St. with a crowd of about 100 onlookers, handed the baby in his arms to a nearby woman, and tossed a rock through Bond’s parlor window. Hoping to call attention to the police, Bond took her pistol and fired a warning shot into the air. Authorities arrested both of them.

With the nascent influenza pandemic mere months away from killing thousands of Philadelphians, the incident sparked what some scholars see as one of the most significant periods of violence and unrest in the city’s history.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pY2Jo4S15hU]

“We may not be able to establish casualty scientifically or historically between the outbreak of disease and the virus of racism, but we understand all too well that when we fear for our very lives, our mortality can shred our civility,” emergency care physician Dr. Jeremy Brown wrote in an unpublished paper quoted in CNN earlier this year.

“This dread exposes a primal panic that unleashes the violent human impulse to blame and hurt others in ways inexcusable.” he said. “There are many lessons we’ve learned from looking at the history of pandemics, but some, regrettably, we never seem to take to heart.”

More 100 years later, Philadelphians bore witness to another pandemic — one that disproportionately affects low-income persons and people of color — in the midst of a countrywide reckoning against systemic racism brought on by the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police.

While the country experienced compounded trauma from social isolation, sustained protest, and a mass death event, the city’s homicide rate and gun violence skyrocketed to levels unseen since the apex of the “War on Drugs”. But with COVID-19 contributing to the rise, those with a bullhorn eschewed solutions in favor of using their bully pulpit to assign blame — a hot topic of debate as the city goes to the polls to vote for a district attorney later this month.

With neighborhood groups, political adversaries, and pundits calling on the city to “do something” about gun violence, or, in some cases, pushing for the top brass to resign, few mention the mayor’s key community initiatives or the effects on which the pandemic had on those efforts. Last year, the Office of Violence Prevention injected almost $1 million into area nonprofit and community groups via their Targeted Community Investment Grants only to see most of those efforts hampered by COVID-19.

“After we were awarded the grant and we went through some training protocols in terms of how to implement it, right in March is when we were going to launch,” Clayton Justice said. Justice is the executive director of the Germantown-based organization Men Who Care. “It was going to go all the way through April and then into May. And so we had to halt everything and everything pretty much was put on hold and a big part of our programming, kind of went to the wayside.”

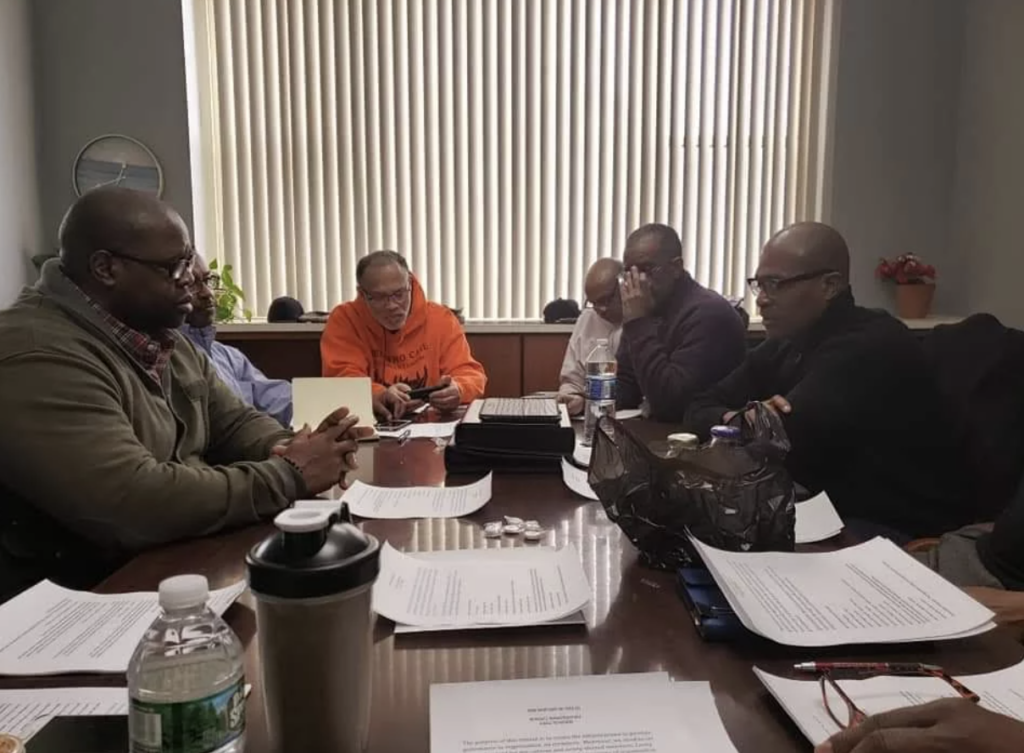

Men Who Care volunteers working on strategic programming, event planning, and initiative building. (Courtesy photo)

Justice hoped to parlay a background in basketball into a tournament for at-risk youth in the Germantown neighborhood, combining mentorship opportunities and anti-gun violence rallies with the moneys awarded by OVP. He told Generocity that one of his ideas was to build a bridge between younger and older generations in the area, close a growing void and open up conversations about community unity. But COVID-19 and the ensuing restrictions that took hold of the city hampered most of his plans.

In the end, Justice, and Men Who Care scaled back their efforts with the Targeted Community Investment Grant, holding a neighborhood vigil and anti-gun violence rally. Less community support for those in need, combined with social isolation and enhanced trauma from a pandemic run amok, left many Philadelphians without support or a place to turn over the past year.

“I can see, even with myself personally, isolation is not something that’s normal and it affects people in a lot of different ways,” Justice said when asked how the pandemic could be affecting the city’s growing homicide rate and issues with gun violence. “I talked to a lot of people who talked about being depressed, and so you can just imagine if, there’s like someone who’s already semi-on edge and agitated, and then you throw [COVID-19] into it and it’s just a perfect storm.”

Social isolation and another rough weekend

Speaking at a news conference in the Sharon Baptist Church’s Hope Café a week before his primary reelection bid, former defense attorney turned Philadelphia’s top prosecutor Larry Krasner told a room full of socially distanced reporters that the city’s homicides to date were 183, a 34% increase point-in-time over last year.

From May 1 through May 7, there were 24 nonfatal shootings, and from April 18 until April 24, there were 196 gun violence incidents, the latter resulting in 100 arrests and 96 cases opened by the district attorney’s office.

A quintuple shooting occurred in Olney over the weekend on the 100 block of East Albanus St., with five persons aged approximately 17 to 23 attacked in broad daylight. In Kensington, a triple shooting took place, while over in the Southwest, a 25-year-old female and a 31-year-old male were victims of gun violence as well. The weekend, Krasner told those in attendance, was rough.

“We will continue to fight for justice on behalf of our communities and families impacted by gun violence,” Krasner said at the news conference. “We will continue our extremely high standards for the quality of the prosecutions that we do for fatal and nonfatal shootings.”

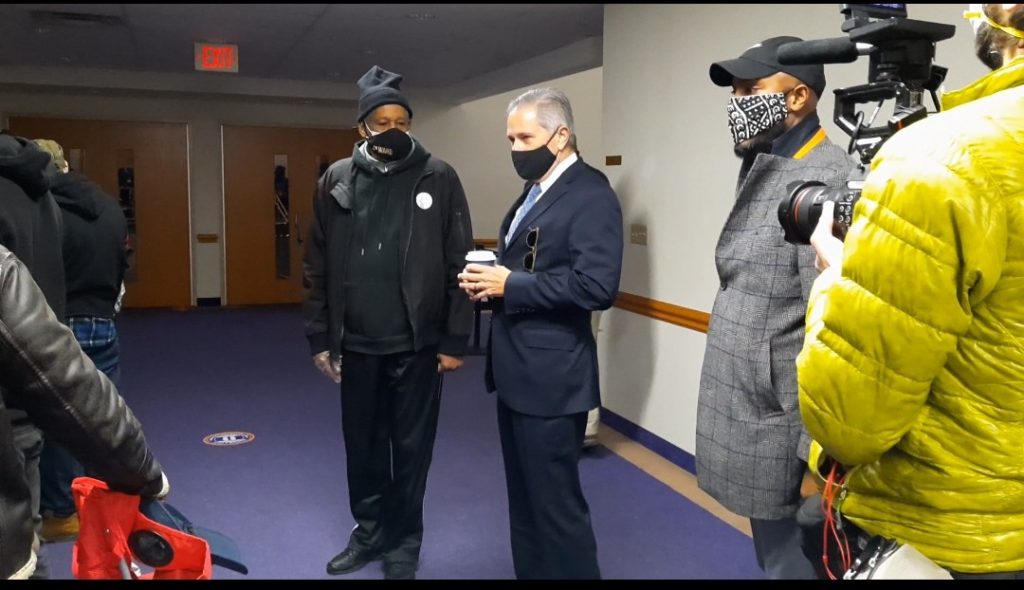

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner made a surprise appearance at the polling place at Triumph Baptist Church, in Nicetown, during the 2020 election. (Photo by Bobbi Booker)

“Our conviction rate, let us be clear, was close to 85% before the courts were effectively shut down [by COVID-19],” Krasner continued.

In 2017, Krasner’s progressive, reform-minded campaign did the unthinkable, emerging victorious from a crowded field of primary challengers to become the de facto district attorney in a city where Democratic voter registrations outnumber Republicans seven to one. But the one-time defense attorney who made a name for himself going up against corrupt police departments and defending Black Lives Matter activists faced immediate backlash from political adversaries such as the Fraternal Order of Police’s John McNesby and then-US attorney William McSwain.

Although Krasner kept some of his campaign promises, making headway on bail reform and stopping death row prosecutions, he faces an uphill battle in his reelection fight against former prosecutor Carlos Vega — a man Krasner fired from the DA’s office — from law-and-order groups opposed to his reforms and progressive activists who think they’re not coming fast enough.

And casting a shadow are the 500 homicides that took place in the city throughout 2020 and the somewhat politicized debate over the pandemic’s effects over it all. Though for those with direct, hands-on experience in these issues, the correlation between COVID-19-related trauma and rising gun violence is quite clear.

“Anecdotally, there are a number of things that we know are happening,” Erica Atwood, senior director of Philadelphia’s Office of Policy and Strategic Initiatives for Criminal Justice and Public Safety. “Folks aren’t able to move, folks aren’t able to maintain employment, some of their housing is a bit unstable. Folks are experiencing anxiety and trauma at higher levels. It’s a pressure cooker. COVID has been a pressure cooker for disaster, particularly neighborhoods that were already at a deficit.”

Among the many things affected by COVID-19 over the past year was Mayor Jim Kenney‘s key initiative — the Targeted Community Investment Grant. Announced at the start of the mayor’s second term as a part of The Philadelphia Roadmap to Safer Communities, the second round of funding went out in early January 2020 to 52 awardees, whittled down from over 300 applications, each of whom received anywhere from $1500 to $20,000. According to a news release at the time, OVP gave preference to those organizations focusing on education and employment opportunities for high-risk individuals between the ages of 16 and 31.

The project was first launched in 2019 when Atwood was a consultant working with OVP. She modeled it off a similar program run out of Minneapolis under that city’s former mayor, Betsy Hodges, with the idea that the grants would be a sustainable investment on the grassroots level. At a time when over-policing is front and center across the country, officials need to trust that communities know best about what they need, Atwood told Generocity. The TCI grants were a way to rebuild that trust in historically divested neighborhoods.

According to OVP’s Program Specialist Kiana Brown, the grant project was successful from the start, with 46 recipients in the first round and 52 in round two.

“We do get a large amount of applications in for the program,” Brown said. “There’s so many people doing amazing work for violence prevention throughout the city. And so we really try to build people’s capacities and that sustainability for their programs and projects. It might be something that’s new or existing.”

But OVP’s largest TCI grant recipient cohort to date ran headfirst into a COVID-19 pandemic that forced cities across the globe to institute restrictive, isolating health and safety precautions.

By necessity, officials pushed the cohort back from February to June, leaving many in neighborhoods disproportionately affected by the coronavirus without much-needed services in a time of compounding trauma. When summer rolled around, OVP worked hard to ensure all programs had enough personal protective equipment or the ability to pivot to a virtual model, but by then, the prospects for many recipients were grim.

To be clear, the office did what it could to fight for justice for communities and families impacted by gun violence throughout the travails of COVID-19. But the year, to paraphrase Krasner, was rough.

Stay-at-home orders and an uptick in violent crime

When it comes to rising homicides during the coronavirus pandemic, the City of Brotherly Love isn’t unique, with major metropolitan areas such as Chicago, New York, Phoenix, and others seeing an uptick of anywhere between 30% and 50%.

Conversely, as gun violence climbed over the past year in Philadelphia, other violent crimes, such as aggravated assaults, rapes, and robberies, stayed at peak lows, as per citywide statistics. With the DA candidates debating the pandemic’s role in the recent uptick of homicides as the election nears, new research might shed some light on whether or not it was a factor.

Last November, researchers at PennMedicine reviewed hospital trauma room visits throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and the previous five years, finding a spike in gun violence cases even as overall trauma visits fell. The study concluded that the “unprecedented social isolation policies,” including quarantines, lockdowns, and stay-at-home orders, correlated with a surge in gun violence and what authors called intentional injury.

Most at-risk during this time were young, African American males.

“Social disruption resulting from the pandemic and statewide stay-at-home orders deeply affects the balance in urban injury management,” Dr. Jose Pascual, an associate professor of Surgery in Trauma and Surgical Critical Care and the study’s senior author, said in a statement. “It can also rapidly exacerbate and worsen the existing hidden pandemic of firearm injury in United States cities.”

Over the past year, Ronald Crawford saw firsthand, almost every day, what PennMedicine researchers found in their study. He’s one of the city’s African American mental health providers, a practitioner of Hip-hop Therapy who offers free therapeutic town halls to returning citizens, and the author of several books, including Who’s the Best Rapper? Biggie, Jay-Z, or Nas, and What’s Free? It Ain’t Being Booked or On Paper.

In a conversation with Generocity, Crawford explained that social isolation stemming from COVID-19 placed an immense burden on many in Philadelphia’s Black communities.

To begin, he said, stay-at-home orders placed some African American men and women into traumatic situations, forcing them into cramped quarters with domestic and sexual abusers with nowhere to go and no one to whom they could turn.

As the courts, parole offices, and other parts of the criminal justice system shut down and pivoted to a virtual format, some at-risk offenders found ways to subvert the system when what they needed was a helping hand. Persons already apprehensive about therapeutic interventions balked at the idea of telehealth, too worried that their vulnerabilities would be exposed online or to others in their homes.

According to Crawford, before the pandemic, young men who were at-risk visited their parole officers, gave a urinalysis, and maybe even received some therapy. Now, things are very different.

“Using drugs every day may impact [a person’s] judgment so that a situation that could have been resolved with conflict resolution and anger management, [that person is] not going to use those skills and because he has a gun on him, you have a possible deadly situation,” Crawford said.

OVP awarded Crawford a second-round TCI grant last year, but like many of his fellow recipients, citywide shutdowns hampered his efforts.

A strong proponent of bringing therapy to the community, Crawford turned to 1970s television. He developed what he called the M.A.S.H. program, an acronym for Mental health first aid After Shit Happens (or, after Stuff Happens, as he politely promoted it for the city). The program was similar to his HipHopPsychoEd sessions, as he secured area recreation centers and offered free group therapy to neighborhoods affected and traumatized by gun violence.

In addition, he promoted literacy through a therapeutic strategy called bibliotherapy. Through a combination of reading and therapy, he hoped to teach his attendees new coping skills. The goal, he told Generocity, was to give people a safe space to share their experiences of violence.

But as COVID became a reality, Crawford struggled to find places to hold his events. Schools, churches, and recreation centers closed down across the city, leaving him scrambling to find new locations. Finally, OVP put everything on hold until June.

“About three months later, [OVP] said, ‘okay we can do it, but you got to have social distancing, we have to do it faithfully,’” Crawford recounted. “I had to spend money to be safe. I bought masks, cleaning supplies. And to be honest, less people wanted to participate. They were really concerned about meeting face to face.”

"People need to heal from trauma, even the people that perpetrated violence."

All told, Crawford held about half of the 20 sessions he initially planned for his M.A.S.H. program, with each one sparsely attended. Going virtual wasn’t an option, he said, as much of his client base already was apprehensive about therapeutic interventions. Telehealth can leave many individuals vulnerable within their own homes, while others still struggle with the digital divide.

As Crawford explained, in this situation, telehealth was more of a barrier than an aid.

But Crawford is not giving up. Recently, he testified in front of City Council on the need for more and better mental health services in Philadelphia, and he’s working on establishing his own drug and alcohol services too.

“People need to heal from trauma, even the people that perpetrated violence,” Crawford said. “I know a lot of people don’t care about the shooters, they think they should be locked up. But oftentimes, the people who are the shooters, they have been victims or witnesses of violence, and are experiencing trauma.”

Lockdowns, trauma, and a human rights crisis

On Christmas Eve, 1990, the Knight-Ridder News Service reported on the killing of a woman in a South Philadelphia bar and another three persons on the city’s West Side. The four homicides put the city at 505 for that year, setting a new record with still one week left to go.

Philadelphia joined several other cities in reaching record-setting levels of homicides in 1990, including Dallas, New York, Phoenix, and San Antonio. Former Police Commissioner Willie L. Williams lamented at the time that America was one of the world’s most violent countries.

“Our homicide rate is going through the roof,” former Philadelphia District Attorney Ronald D. Castille had said a few months earlier. “It’s just raining a hail of bullets out there on the streets. Three weekends ago, 11 people were killed in a 48-hour period.”

That summer, Williams voiced his support for a U.S. Senate effort to ban semi-automatic assault weapons, but, according to an article in The New York Times, he worried that doing so would have no immediate effect on Philadelphia’s worsening problems. “There are so many of these weapons around,” the Times quoted Williams as saying.

In an industry powered on the motto “if it bleeds, it leads,” it was rare to report on economic hardships, societal pressures, and internalized trauma within the daily crime statistics and homicide headlines.

But according to Dr. Eric Edi, chief operating officer of The Coalition of African and Caribbean Communities, or AFRICOM, COVID-19 has put real pressures on families and individuals this past year, both personal and economic. While he cautioned that he performed no studies on the matter and that his thoughts are mainly anecdotal, he does agree that there is a link between the pandemic and the rise in violent crime in the city.

Over the past year, AFRICOM saw an increase in the number of people seeking assistance, especially from newcomers who don’t typically ask for help. Dr. Edi said there was a massive spike in people asking for appointments with his organization and large numbers of families needing help from their cash assistance program for those affected by COVID-19. There were people who developed an alcohol use disorder over the past year and some struggling with the consequences of domestic violence.

“The risk of poverty in Philadelphia is already very high,” Dr. Edi said. “When you add COVID-19 on to that, of course, it is going to create another level.”

"The epidemic is a human rights crisis, and nobody is immune against that."

Like so many others in Philadelphia last year, Dr. Edi found himself stymied by the pandemic. He, too, was a second-round TCI grant recipient, with OVP funding his youth soccer initiative for African and Caribbean immigrant youth.

The program, called Building Safer and Engaged African Immigrant Communities Through Soccer, included the Sudanese American community soccer program, the Sierra Leone Youth Association, the Red Ranger program, and Salone Fc. It was a project that would impact over 200 children and families.

Public health and safety precautions impacted sporting events as such that even when things began to open, there wasn’t much Dr. Edi could do to bring the program back on track.

In the end, the only project able to move forward was the Red Rangers program, he told Generocity. But like everyone else, Dr. Edi continues to push through. He’s putting pressure on the city to ensure testing and vaccinations for African communities and making it known that any and all economic packages should include all people, regardless of their residential status.

“The epidemic is a human rights crisis, and nobody is immune against that,” Dr. Edi said.

Of course, OVP did its best to help and offer guidance to all grant recipients as they attempted to traverse what was an impossible situation for many. And through it all, several awardees did press on or even thrive, pivoting to a virtual format or taking advantage of outdoor congregate settings as health and safety rules allowed.

One of those recipients was Ebonie Dukes, president and executive producer of MyNEWPhilly, a news media platform that highlights the positive aspects of Philadelphia. Dukes developed a talent incubator, allowing attendees to learn about careers in entertainment and media and lessons on financial independence.

Dukes told Generocity that the key to her incubator is on-the-job experience. She doesn’t want to give people the tools to do something without showing them how it can be used in everyday life. While the pandemic made that near impossible, she was able to use online workshops to show her students “the business part of the business,” as she said. Talent incubator attendees learned how to craft a proper email, create graphics for a piece of content, and other important things, all in a virtual format.

“It was challenging to say the least, but we made it through and ultimately I think it helped us impact more people,” Dukes said. “We were able to reach more people being online.”

Jane Golden is the executive director of Mural Arts Philadelphia, and she’s one of the busiest women in the city. Right now, she’s working on a project related to migration with an artist from Bogotá, another on abolition, and a series of projects in Mural Arts’ Porch Light Program with people experiencing trauma, housing insecurity, and substance use disorders. In addition, she’s working on projects with veterans and people experiencing homelessness, as well as a mosaic on The Concourse underneath City Hall.

And last year, her Community Resilience (Stop Gun Violence), a second-round TCI grant recipient, worked straight through the pandemic.

The program, designed to use interactive art activities to promote safety, resilience, and trauma-informed approaches, took advantage of online workshops and the outdoor canvas that is Philadelphia.

“The wonderful thing about mural making is, it’s outdoors,” Golden said. “We did virtual programs and then we partnered with the Department of Public Health. We were able to do … posters and decals all about public health messages. All the boarded-up stores, we were able to do lots of murals.”

“We tried to be value-add in every way possible,” she continued.

Vaccines, reopenings, and another round of grants

The angry mob of white men and women surrounding Bond’s home in 1918, followed by the now infamous gunshot fired by Bond herself, threw Philadelphia into chaos, as racial tensions, a country at war, and a soon-to-be deadly pandemic put the city over the edge.

Black men were chased down the street and beaten within an inch of their lives by crowds of white people screaming, “lynch them!” Police used an early form of stop-and-frisk to hold over and arrest persons from the African American community on trumped-up charges while groups of white people committed acts of violence with impunity. At least two men were victims of police brutality, including Riley Bullock, killed by a bullet from his arresting officer’s gun.

The patrolman was tried but found not guilty by a jury of his peers. By the fall of that year, the influenza pandemic took hold of the city, with “bodies stacked like cordwood,” as they said at the time.

“There are chilling parallels between what we have seen in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic with the revelation of quite brutal police killings of African Americans and what actually happened back in 1918,” Dr. Brown told CNN. “That story is a very sobering one — not least for which it reminds us that this kind of violence against the African American community is nothing new.”

"There are chilling parallels between what we have seen in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic ... and what actually happened back in 1918."

But with the world still trying to solve last century’s problems, it’s important to note that Philadelphia continues to persevere. In April, OVP announced a third round of TCI grant winners, and while the pot was a little smaller this go-round — $400,000 compared to $1 million — with only 30 recipients down from a high of 52, the goals remain the same.

City officials are turning to community-based organizations, groups on the front line of Philadelphia’s gun violence issue. The new cohort of grant recipients includes a wide array of programs, Kiana Brown told Generocity, including everything from training programs, welding programs, mentorships, and one-time events.

Whereas last time OVP was caught off-guard with having to pivot, both to virtual formats and to accommodate health and safety protocols for COVID-19, this cycle, everything is baked into the funding, with such things as PPE paid for through the grant.

And there will be an extra level of collaboration between recipients to help programs break out of their silos.

“People are able to not only work together but recruit in different areas,” Brown said. “There might be something that’s happening in West Philly, like a welding program, that someone in North Philly has a participant.”

“[We’re] trying to make sure that we’re able to build those bridges,” she added.

As for the grants themselves, they remain a part of OVP’s future plans.

“If we really want to get at what are the drivers of violence, we have to invest in community,” Atwood said.

OVP isn’t the only city office using community-based grants to fund preventive anti-gun violence initiatives. A week before his primary reelection bid, Krasner used the power of incumbency to announce a new round of grants for community and nonprofit organizations totaling $125,000.

Using funds from what the district attorney’s office called the “lawful and appropriate use of civil asset forfeiture,” five organizations received $25,000 each, including The Institute for the Development of African American Youth, Give and Go Athletics, Black Women in Sport Foundation, Savage Sisters Recovery, and Mighty Writers.

According to a statement, the funds will be distributed and audited by the Philadelphia Foundation. At his news conference, Krasner called on others from public, private, and academic institutions to contribute $100 million to the grant effort.

“When we speak about gun violence, we all know that there is no family that considers the solution to the problem of losing a loved one to be what happens in a courtroom,” Krasner said. “We all know the solution is not to lose that loved one in the first place. And that is why I am so pleased to be in a position to be part of a solution that points toward prevention today.”

After the district attorney announced the current slate of grant recipients, he noted that the next round of applications would open immediately.

In July 1918, the Philadelphia Inquirer described Bond as “a short young woman of light brown color, with a quiet but emphatic manner.” She told the magistrate that she was determined to stay in her house.

“What am I to do?” the paper quoted her as saying.

That weekend, a century ago — to paraphrase Krasner again — was rough.

Project

Porch Light ProgramTrending News