Where does Philabundance go now?

May 13, 2022 Category: Feature, Featured, Long, MediaAs the pandemic raged and the economy shut down, hunger surged.

Inside the country’s food distribution nonprofits, staff were wrecked by crippling demand. By summer 2020, Kimberly was drained. She was inspired by working with “the most amazing people in the world.” But the strain of an already-demanding job felt relentless.

“You wear multiple hats and that’s expected. That’s what many of us do and sign up for when you work in a nonprofit, because you want to help,” said Kimberly (which is not her real name). “There are the most hardworking people you’ll ever meet working to make sure that everybody in their neighborhoods and their communities were fed.”

But everyone has limits.

In Philadelphia, a patchwork of social services organizations lurched forward to respond. In 2020, almost a third of Philadelphia children experienced food insecurity — 30% growth over the year prior, according to Feeding America, a national network of food pantries. Overall hunger peaked and then remained elevated at 17% in 2021. Today, high inflation has driven up food costs, hitting poorer Americans the hardest and threatening the food bank system.

“We did everything we could to meet the need,” said Kimberly, who was working at Philabundance, the standard-bearer of Philadelphia’s anti-hunger strategy. Inside, the nonprofit’s growth was historic:

- The organization distributed 55 million pounds of food in 2020, according to the group, the most ever and 60% more than the year previous;

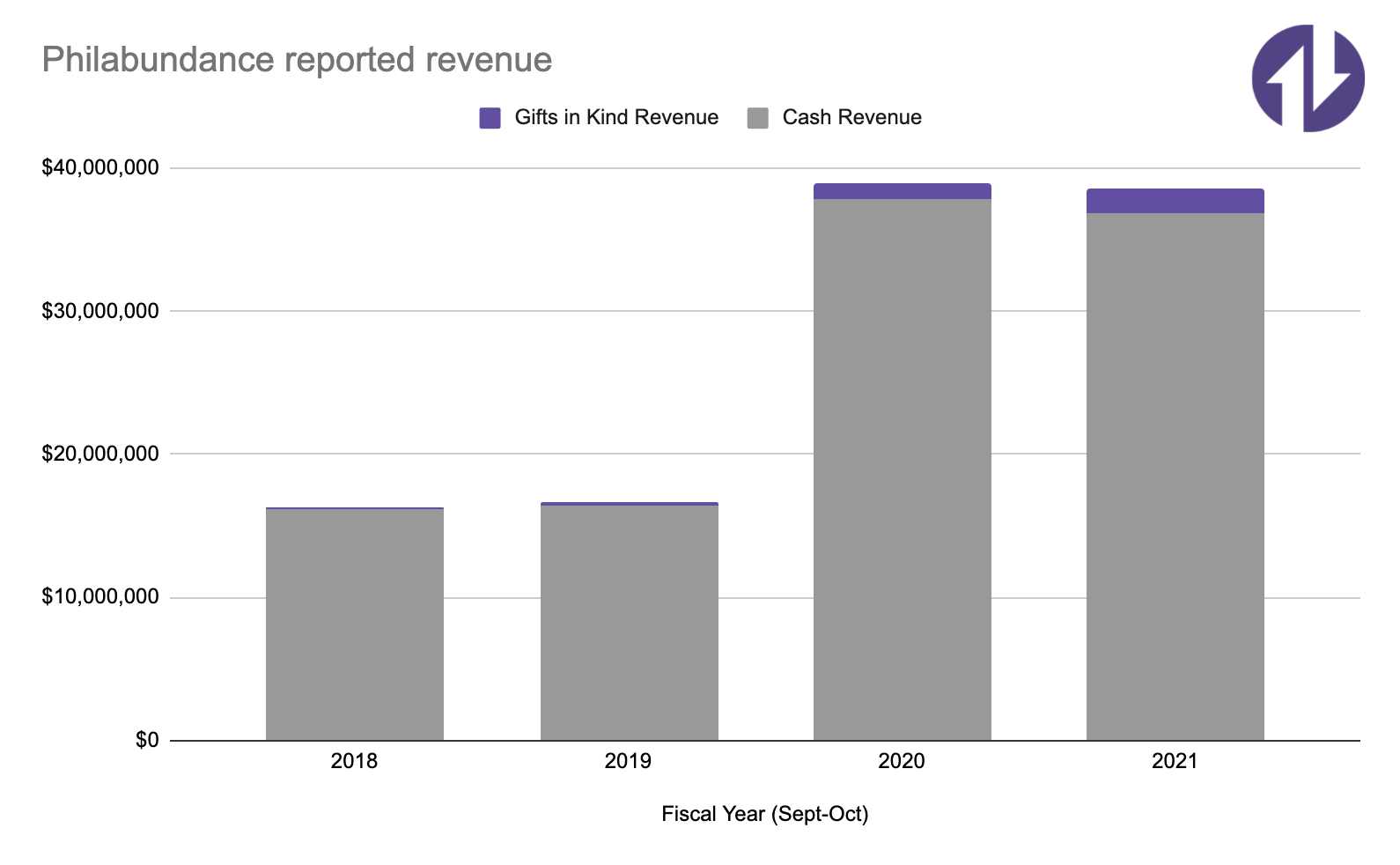

- The nonprofit’s cash revenue more than doubled year over year to more than $37 million, according to a spokesperson;

- In 2019, the total of in-kind donations was below $250,000. In 2020, it was more than four times that, exceeding $1 million. The total grew again in 2021;

- When also including donated food that Philabundance distributes to its “agency partners” for in-community programs, the organization’s total take exceeded $100 million in the most recent fiscal year, according to its federal 990 form, a near doubling.

Those growth numbers better resemble a fast-growth tech startup than a staid social services nonprofit. If that wouldn’t stretch an organization enough, as one of the region’s largest anti-hunger organizations confronted the most challenging period in a 35-year history, it was undergoing a major internal transition as well. In a dozen interviews over the course of months of reporting, Technical.ly, in partnership with our sister-site Generocity, has learned of widespread organizational turmoil inside explosive growth in the face of historic challenges. The hunger needs of many of Philadelphia’s most vulnerable residents are in the balance.

##

In March 2020, Glenn Bergman, who had been executive director since 2015, transitioned out. Two months later, a new executive director was named: Loree Jones, who had been a chief of staff at Rutgers University-Camden. Jones, who had also previously worked at the School District of Philadelphia and CityYear, is a veteran of big institutions in the region — a distinction from past Philabundance leaders. She stepped into leadership at a chilling time.

“Health and food insecurity, global health, racial awakening,” said Jones in an interview last week. “Oddly enough and frankly, I feel really honored and privileged to have this opportunity to serve in this way and this moment … to navigate through these challenging times.”

Those challenging times have coincided with the so-called Great Resignation, as employees quit en masse — like they have during other historic periods. Philabundance was not immune. Turnover started at lower-wage and mid-level roles, many with long-held institutional memory. Then prominent members of the leadership team followed. This month, the nonprofit’s chief financial officer, who only started her role in fall 2020, Gina Harlan, was the most recent departure, as first reported by Generocity and confirmed by a spokesperson.

Philabundance leadership say this is the expected result of a food insecurity system stretched to the max. Former and current employees are warning: Philabundance is buckling under the weight of unprecedented need. With threats of another recession looming, the region’s safety net needs to be strengthened now.

What is Philabundance’s place in Philadelphia’s social services system?

In April 2020, Share Food Program became the region’s largest hunger relief organization in the region, by poundage of food served, according to that group. It was a humbling fall for Philabundance, giving way to Share, which is now led by George Matysik, who himself once worked for Philabundance.

The transition started a year prior when Share Food began serving “through our region’s National School Lunch Program to nearly 800 schools,” a spokesperson said. But it marked one more existential question for a new Philabundance executive director to confront.

Jones downplays the dynamic. “It is not unusual,” she said, for a region to have multiple food distribution agencies, and the groups collaborate. For example, both are members of Hunger Free Pennsylvania, she said.

Of the estimated 300,000 Philadelphians who experienced hunger in 2020, it’s likely none especially care about the elaborate network of providers, nonprofits and government agencies that serves as a well-worn anti-hunger safety net in one of the world’s richest countries. But that system has very real consequences — even more so as a new stage of economic turmoil looms.

Philabundance began in March 1984 as an early food rescue program. Founder Pamela Rainey Lawler’s early innovation was to focus on logistics: Restaurateurs and caterers were willing to donate food and community organizations wanted to give food out, but no one was matching supply and demand. Rainey-Lawler started doing it herself. It worked, and the organization grew, following national trends of logistics-heavy food banks.

In the early 2000s, Philabundance grew into a regional food-distribution powerhouse under influential executive director Bill Clark. The social services engine was a regional clearinghouse for donations, maintaining large-scale distribution facilities to send food to hundreds of partner nonprofits that primarily lead the direct service. Witness a soup kitchen or neighborhood food pick-up program and they may partner with Philabundance. That’s representative of broader trends, as a growing national network of food banks coordinate resources.

Clark’s successor in 2015 was Glenn Bergman, who had spent a decade leading Weavers Way, the community food co-op founded in Mt. Airy in the 1970s. Experienced in small-scale community food nonprofits, Bergman’s tenure was known for a softer touch in contrast to Clark’s rapid growth.

Over the decades of Philabundance’s existence, anti-hunger efforts professionalized well beyond what one volunteer might imagine. The 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to researchers focused on making food distribution systems more efficient — other economic research has followed. Food banking has grown big.

Bergman oversaw a five-year strategic plan that was largely defined by two key phrases: “ending hunger for good and relieving hunger for now.” Over that time, as Philadelphia has remained stubbornly poor and hunger has remained stubbornly entrenched, successive waves of social innovators and nonprofit founders have attempted to readdress the persistent threat.

Among them was Matysik, who spent six years at Philabundance, mostly under Clark’s leadership, before he took over the Share Food Program in March 2019 — 35 years to the month that Rainey-Lawlor started the Philabundance journey. Share Food Program was founded in 1986 as a food co-op and has addressed hunger for years, but 2020 was also a breakout year for its offering: Its income and expenses both nearly doubled, according to its 990 filings.

Will The Great Resignation threaten how Philabundance delivers services?

Loree Jones began her tenure as Philabundance executive director at the most tumultuous period in the organization’s history.

Unemployment, hunger and urgent need spiked. Then the horrific police murder of George Floyd was captured on video, and the country’s largest racial justice protests in a half-century broke out. Jones is Philabundance’s first executive director of color — though she clarifies that she was hired before the Floyd protest movement.

These are weighty and complex issues to confront, never mind that new models for food distribution have challenged Philabundance’s preeminence in servicing Philadelphia’s desperate hunger issues. None of these are challenges of Jones’s creation.

“This is a tough time to be alive,” she said, directing her attention to the people her organization serves.

Most would give a leader ample latitude to navigate in these difficult times. Yet two years into her tenure amid persistent strain, Jones faces scrutiny. Has staff turnover gone beyond industry standards? Philabundance leadership says no.

In the last year, Philabundance has seen 32 people resign from the organization for a range of reasons, meaning a 17% turnover rate, according to records provided by Philabundance. That rate is actually lower than the national average and even lower than what took place the year before Jones took the role. Moreover, an organization spokesperson says Philabundance has grown in response to demand. When Jones started as Philabundance executive director in June of 2020, the organization had 115 employees, according to internal records. As of last month, the nonprofit had 193 active positions, including 179 current employees and 14 open positions. Philabundance Chief People Officer Michele Gilbert said the organization has promoted 24 people in house the last fiscal year to meet the growing need.

At most nonprofits, “people are always asked to do more with less,” Jones said. “But we were looking to do better with more.”

Jones enthusiastically cites an array of employee-engagement initiatives that remain rare among social services organizations. In her tenure, there was a wholesale compensation review, additional org-wide paid time off and monthly employee-engagement activities added. Jones says she takes criticisms of burnout seriously. Concerns of staff turnover do not bear out in the data, leadership says.

Critics say that those numbers hide just how dire internal team culture is, evidenced by high-profile departures.

Heads turned when Philabundance veteran Melanie Cataldi left last month, ending a 20-plus year tenure as chief impact officer. Cataldi did not respond to requests for comment, though two weeks ago she posted a social media message: “People don’t lose their motivation and inspiration overnight.”

Nonprofit observers caution that it isn’t uncommon for long-time execs to leave when a new CEO comes in. That’s why the departure of CFO Harlan, who was hired by Jones, stood out. Though a Philabundance spokesperson declined to comment on personnel matters, Jones confirmed to Generocity there is no expectation of legal action.

“I am confident that the financial side of things is better than it was,” Jones said.

The chairman of the Philabundance board of directors, John Hollway, gave Generocity this statement: “The Board made the unanimous decision to hire Loree Jones as our CEO in June of 2020, three months into the COVID-19 pandemic. The Board is proud to support her in these efforts. She also, as one would expect of a new CEO, focused on ways that the operations and performance of the team could be improved. A transition of that type often carries with it changes in personnel even in non-pandemic times.”

Other current and former Philabundance employees who did speak to Generocity requested anonymity to protect their future employment. We have granted their anonymity after independently verifying their work status and portions of their claims. Generally, their criticisms argue the organization’s new leadership team, led by Jones, has moved too slowly in defining a clear vision in such troubling times. Recent unfavorable employment ratings on Glassdoor, which are anonymous, echo that sentiment.

“We were made to feel as if we weren’t the experts in our field and if we tried to assert ourselves as such, it was taken as insubordination,” Kimberly said. “I heard that word ‘insubordination’ very often.”

What will change with the next Philabundance strategic vision?

One big theme from those current and former employees relate to the Philabundance strategic vision. The organization was effectively operating within a lapsed five-year plan when the pandemic hit and Jones was hired.

Pandemic or not, interviewed staff say they’ve gone two years without a new plan on where the organization is headed, amid a pandemic and contested stature as the region’s preeminent anti-hunger nonprofit. Jones has led a new vision-building process that has lasted at least the last year. Burnt out and nervous, several employees say the process has been too deliberate.

“What are the motivations for this leader? What are her goals? What direction is this organization moving in? None of that has ever been really clear,” said one employee.

That consternation has reached out into the Philabundance community. Former executive director Bill Clark told Generocity: “I have heard many of those concerns voiced through alumni but originating with current employees.”

Jones says the wait is nearly over. She expects her new strategic vision to be unveiled next month, before the end of the organization’s fiscal year. (Currently Philabundance is operating a “stub” year, as it transitions to a June to July fiscal year.)

She says no major shakeup looms, as she came to the organization for its existing mission. “I was drawn to its commitment to end hunger for good,” Jones said in a virtual town hall weeks after she started in 2020.

One update may be a focus on “people not pounds,” which Jones says refers to a move toward “nutritional security” and not just “food security.” This is tied to a trend of ”asset-based” language in the social services sector. To do that, Philabundanec will retain its partnership model, Jones said.

Jones says Philabundance has invested more in their agency partners amid the last two years of growth, and that will continue in the new strategic vision. In this version, Philabundance remains a central clearinghouse for cash and food, which it then distributes to community-level organizations. “That partnership will strengthen,” she said.

Will Jones lead Philabundance through the next five-year strategic vision? Yes, she told Generocity confidently. Given all the turmoil, is she surprised by the staff criticism?

“I’m not going to say people shouldn’t feel their feelings,” she said.

Gilbert, the chief people officer, adds that leadership has communicated its vision during this strategic planning process.

“Loree held an all staff meeting in July of 2021 in which she detailed the organization’s plan and priorities for the upcoming year,” she said. “At this meeting, departments worked on a group activity to explain how they would implement this new vision in their daily operations.”

Gilbert added: “Loree knew the importance of outlining a direction for the organization and knew that a strategic plan may take several more months to complete, so she did not wait for the strategic plan to conclude but worked directly with staff to share areas of focus for the organization.”

As the executive director of a crucial anti-hunger organization in the country’s poorest big city, Jones is among the country’s most important nonprofit leaders. She also happens to be a woman of color. Given an ugly narrative of putting undue criticism on Black women leaders, it’s worth questioning: Is this undue scrutiny?

“I’m an African-American woman living in America,” Jones said. “Some of this comes with the territory.”

As one regional nonprofit observer put it: “Philabundance is important enough to warrant critical attention no matter who is leading over there.”

What happens next?

One longtime Philabundance veteran had been passionate about working in food banking and had worked her way up to a senior manager position. “Making a decision to leave was really difficult for me. I debated it for months. I left because I felt like my values didn’t align with those of the leadership of the organization,” she said.

Other former and current staff members interviewed expressed hope that a turnaround is possible. Some turnover is to be expected, and hunger remains elevated in Philadelphia, so the need is there. Staff hope a new strategic vision can offer clarity and start fresh. We need more urgency and more willingness to be heard, said one staffer.

What lessons are there for other organizational leaders? Amid crisis, communication needs to increase. Staff get nervous quickly without clear direction and strategy, especially during periods of leadership transition. Confidence in leadership can turn quickly, so take early criticism seriously.

For Philabundance’s part, Loree Jones says she understands. Early in her tenure, someone came to the Philabundance administrative offices. He had never needed emergency food before and was nervous and scared. That was an early reminder of how high the stakes are.

Amid that need, Kimberly, the Philabundance employee from the story’s beginning, kept trying to find the motivation to stay longer, but couldn’t. Her mental and physical health had declined. She lost about 12 pounds.

“What we were doing for clients was amazing. We put out more food than we ever had. We served more communities and people than we ever had. We developed different programming to meet the needs that were happening during the pandemic,” she added, but the organizational change was too much. “I need to do what’s best for me and exit stage left.”

Trending News