Empowering the living by memorializing the lost in North Philly’s Village

December 6, 2016

Category: Feature, Featured, Long, Purpose

December 6, 2016

Category: Feature, Featured, Long, Purpose

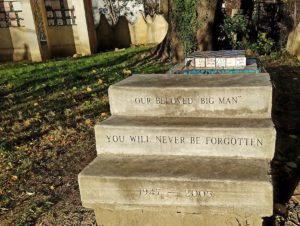

Anchored down in a grassy North Philadelphia lot off Germantown Avenue is a concrete stoop with three steps that lead to nothing.

No porch, no platform, no pavilion. Instead, every pair of passing eyes stops at the four words engraved across the top step: “Our beloved ‘Big Man.'”

This plot of land is one of a number of “art parks” settled around the Village of Arts and Humanities. The parks are alive with multicolored monuments and mirror-clad mosaics. There are three decades of installations stitched across James “Big Man” Maxton’s North Philly neighborhood. Every sculpture is a memorial. The stoop is no exception.

“You will never be forgotten,” reads the second step, followed by “1947-2005” on the third.

There’s an undeniable energy radiating from the parks around the Village. It’s surreal, and Lillian Dunn, a program manager at the community arts nonprofit, agrees. Several pieces act as guardians, protecting neighborhood children from evil, said Dunn, standing before a mural of a small troop of scepter-wielding angels.

Big Man helped create that piece. He was a drug addict-turned-drug-dealer-turned-artist-turned-community builder. A beacon of hope on North Philly’s Badlands border, and he’s still revered. Dunn said his name is more than likely to come up in any given neighborhood conversation — indeed, two passersby dropped Big Man’s name mere minutes later — and in many ways, his legacy has continued to empower the community he championed.

As for the stoop? That was where he held every community meeting. It now stands sentinel in front of another memorial — a wall dedicated to community lives lost to violence over the years.

These memorial structures are unique to the Village, but this is not how the lost are typically memorialized in North Philly. You’re more likely to see candles placed in mugs on the street, like Nigerian sculptor and performance artist Lanre Tejuoso did when he started his residency at the Village this past summer.

“The mug is used in the house, not for putting a candle inside it. What is a candle doing inside this beautiful mug?” Tejuoso remembered thinking.

Tejuoso, who works with discarded materials, and Ghanese artist and writer Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh are both in Philadelphia participating in SPACES, an artist in residence program Dunn heads up at the Village. Think of SPACES as a big cross-cultural community art experiment: Over the course of nine months, foreign artists work with neighborhood artists and community organizers to build out a community art project that explores particular motifs.

Ohene-Ayeh is hosting a series of artist discussions to explore “local creative power.” Tejuoso is using discarded materials to explore cultural traditions of memorial and loss. And seeing a lit candle in a mug did not land with the Nigerian sculptor.

“The space where people would come for a memorial to remember their loved ones is very different from what I used to learn back in Africa,” he said. “We remember our people, but not in such ways.”

Stan Ward is one of the community organizers working with Tejuoso. He said there’s some common ground between the two cultural traditions, like the whole community paying respects at a memorial when a life is lost.

“They dress in all black, too. We have rest in peace shirts, teddy bears and balloons. They bow their head and say a prayer,” Ward said. “And they’re not used to seeing liquor bottles.”

Ward said it’s been the process of coming together as a community, in memorial of community and for the purpose of creating art as a community that’s been eye-opening.

“We’ll sit around in a sewing circle, we’ll tie knots together and you know, just talk about a little bit of everything,” he said. “In a way, that brings our community together, too. I’ve met new people I’ve never met before.”

That includes elementary school students at nearby Hartranft Elementary. Ward introduced the students to the project earlier this year.

“It was a little field trip for them, something to keep them up out the streets and stop them from doing all the nonsense with all the crimes and stuff going on,” he said. “We talked about their loved ones that passed. Their friends.”

The students aren’t the only ones. In a first-level room tucked into the Village warehouse on Germantown Avenue, a handful of neighbors are sewing thread through cardboard squares. The materials might be considered trash by some, but the final products cascade like waterfalls.

“I imagine this in my head,” said Sherita Dill, pointing her red plastic sewing needle at the mess of materials draping down the wall behind her. “These can be used for waterfalls, and these can be halos.”

This project is providing Dill with the closure she’s been seeking.

“I have a lot of people that passed. This is really helping me get through,” she said. “I lost two sisters. I feel like my one sister’s death, I didn’t really get over it. This right now, this is making me have closure. This is nice.”

And in many cases, like this one, the resulting work is beautiful. In others, it’s sobering — like this sculpture by North Philly artist Ruben Antonio Gutierrez, composed of the materials and vices that took the lives of his loved ones.

But in a neighborhood full of testaments to loss, they seem right at home. Big Man would be proud.

Work from this cycle of SPACES will be on display Friday, Dec. 9 through Jan. 31.

Trending News