Organizers and activists clash at the crossroads of Philly’s housing crisis

July 29, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

July 29, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

Updates

Updated to include Herman Arce's association with the Philadelphia Housing Authority and the Brewerytown Sharswood Community Civic Association. (August 18, 2021 at 5:37 a.m.)Long before former Philadelphia Mayor John F. Street’s Neighborhood Transformation Initiative became the centerpiece of his administration in the early aughts, he was a celebrated housing activist who championed squatter’s rights.

In the early 1980s, as a City Council representative of a North Philadelphia district with 11,000 abandoned homes, he scored a legislative victory guaranteeing squatters the right to occupy vacant domiciles within 12 months. The bill was the most significant achievement of his early career, Street told the Inquirer at the time.

But it’s 40 years later, and those same fights rage on in a city of neighborhoods segregated by race and class.

Today, with Philadelphia at the intersection of a global pandemic, Black Lives Matter demonstrations against police brutality, and a nascent economic downturn, two generations of housing and community activists are torn over how to continue Street’s legacy.

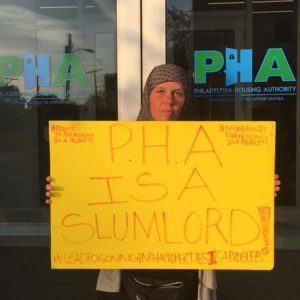

At the center of the battle for low-income and affordable living in the city is the Philadelphia Housing Authority, the country’s fourth-largest housing authority and number one landlord in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Earlier this year, local activist group Occupy PHA initiated the most substantial housing takeover in the United States, helping over 40 people — mostly single mothers and their children — move into abandoned PHA properties. The group has helped these families rehab each home, giving them a liveable abode at a time when affordable housing is scarce, and four walls are necessary due to COVID-19.

“I saw what they were doing in other cities and realized that they have so many empty houses here in Philadelphia,” said , a housing activist and founder of Occupy PHA. Bennetch was inspired by groups in Los Angeles, Oakland, and other cities that have done similar takeovers.

While Occupy PHA has a list of demands they’ve presented to both the city and the housing authority, according to them, their needs are straightforward. The city has vacant properties, and they want them placed in a permanent, low-income community land trust.

What the group doesn’t want is the government’s help, they said. According to Occupy PHA, they don’t want the red tape or overhead that comes along with the bureaucracy.

On the other hand, however, is a North Philadelphia neighborhood desperate for economic revitalization. As part of their citywide demonstrations, the Occupy PHA movement has taken over a vacant lot next to the housing authority headquarters on Ridge Avenue, an offshoot of the James Talib-Dean Camp for people experiencing homelessness on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Like its sister camp, the PHA occupation is a place where unhoused Philadelphians can gather together to feel safe and avoid the trauma associated with the city’s “Service Days.”

But according to the housing authority and members of the surrounding Sharswood community where the encampment is located, the demonstration is blocking a $51 million transformation project where construction of a grocery store, bank, urgent care, and 100 new affordable housing units is set to begin.

The project is part of a larger revitalization effort in the area that began earlier in the decade and saw the implosion of all but one Blumberg property as well as the rehabilitation of Vaux High School, which brought community and health services to Sharswood.

“The community really, really, really wanted a grocery store, understanding that Sharswood is, in fact, a food desert,” said Rev. William Brawner, who recently was named pastor at Mother African Zoar United Methodist Church on Broad and Westmoreland. He was previously at Haven Peniel Methodist Church and is active in the community, having worked to stop the development of several Stop-n-Gos in the neighborhood and set up HIV testing at his church, among other things.

“[Grocery stores, banks, urgent cares] are things that we have not had since the 60s,” he continued. “I understand protesting. I am about protesting, power to the people, am all about freedom of speaking, but there’s also protesting and then there’s partnerships. I consider myself a protester `through and through, my record speaks to that, but there has to be a time after protesting, you have to have a plan and you have a partnership and everyone has to come to the table.”

A poor neighborhood in America’s poorest city

On August 28, 1964, an African American woman named Odessa Bradford was arrested by two Philadelphia police officers following an argument that ensued after her car stalled at the intersection of 23rd Street and Columbia Avenue. The resulting race riots, one of the first of the Civil Rights era, lasted for two days, leading to the destruction of North Philadelphia’s mostly white-owned businesses.

They also marked the start of a decades-long economic decline for Black communities in the area while giving one man carte blanche to institute a punitive form of over-policing. That man was former police commissioner and the 93rd Mayor of Philadelphia, Frank Rizzo.

Today, North Philadelphia’s Sharswood/Blumberg neighborhood stands as one of the poorest in America’s poorest big city, with a poverty rate hovering above 50%. Eighty percent of all residents in the area are unemployed, and there are nearly 5.5 homicides per every 1,000 people. Over 1,300 houses — accounting for roughly one-third of the neighborhood — are vacant or abandoned. And gentrification continues to be an issue across the city.

Revitalization efforts in Sharswood/Blumberg kicked off last year with the opening of the housing authority’s brand-new, $45 million headquarters located along Ridge Ave. The project was seven years in the making, according to PHA officials, beginning in 2013 when the housing authority received a $500,000 planning grant for the Sharswood neighborhood.

Through a series of community meetings and engagement events, residents made known their desires for the area, including the aforementioned grocery store, the demolition of the Blumberg Towers, and the addition of affordable, safe, low-income housing.

“[The PHA] came into this community back in 2013, and they said ‘hey, this is our Choice Neighborhood Initiative Plan, this is what we would like to do, we want to bring some economic development,’” said Darnetta Arce, an area resident who has lived and been active in the community for 20 years. She currently serves as the executive director of the Brewerytown Sharswood Community Civic Association.

It should also be noted that Arce is the spouse of Herman Arce, who has worked off-and-on at the PHA since 2008 and currently serves as vice president of the Brewerytown Sharswood Community Civic Association.

“They wanted to make sure that people who wanted to remain in this area or who desired to live in this area could, because they will be offering subsidized housing through their programs whether it was rental or home ownership,” Arce continued.

Bennetch and other activists at Occupy PHA dispute this narrative, arguing that the housing authority’s plan to transform the blighted neighborhood was all a ruse. They point out that the PHA used eminent domain to seize over 1,200 properties in the Sharswood community, including homes that had recently been sold at auction by the agency itself.

Bennetch alleges that the PHA has a history of falsifying documents and other homeowner records to evict tenants and seize properties. The agency isn’t a provider of low-income housing, says Bennetch, they’re the largest perpetrators of gentrification in Philadelphia, selling off land to greedy developers. PHA denies all of these accusations.

In recent weeks, Bennetch’s activism, and that of Occupy PHA, has come in direct conflict with the housing authority, raising tensions with stakeholders throughout the community. Recently, a fire broke out at one abandoned PHA property, with officials placing the blame on squatters. Bennetch, however, said that claim is false because the vacant house had no occupants.

“Of course a house that’s left in disrepair is going to be unsafe,” she said.

At the end of June, Bennetch and others received formal notice from the PHA that the Ridge Avenue encampment next to the agency’s headquarters was illegal.

“If you attempt to remain on this parcel of PHA property, you may be subject to legal action, including arrest for criminal trespass and potentially other charges,” stated thePHA letter signed by Laurence Redican.

"White people have no business speaking for Black people who don't even know them."

Despite several attempts to shut it down, the camp remains active and is going strong, according to Bennetch.

But Sharswood residents and community organizers, many of whom support the work the housing authority is doing in the neighborhood, are asking the Occupy activists to take a step back.

“Black people are fully capable of leading Black movements,” Brawner said. “That community needs to elect or put someone in place to speak for them. White people have no business speaking for Black people who don’t even know them.”

A safe, comfortable home for her kids

With a little help from some Occupy PHA activists, Laurel — who asked that her real name not be used — put up some paint and brought some furniture to the housing authority property she’s taken over with her kids. “It looked like an abandoned home,” she said, describing her first day in the house a little over a week ago. “But with a little love and hope we turned it into a home and you wouldn’t even believe that it’s the same home.”

“Within a week, me and my kids are [now] comfortable,” Laurel said.

Like most Philadelphians, Laurel’s first priority is her children, and her goal is to protect and keep them safe. That battle became more difficult in 2011 when her mother, with whom she was living, passed away, forcing her to bounce around between family, friends, and the shelter system. She had to separate her kids so often, which confused her children and broke her as a parent.

“And then I was offered [this PHA property], and I’m grateful,” said Laurel, who repeated that everyone should have a home for their kids.

Laurel spent 15 years on PHA’s waiting list, which she described as stressful and disheartening. After struggling to keep up with the requirements and desperate to keep her children safe, she eventually fell off the list. Occupy PHA leaders consider the waiting list to be among the housing authority’s most significant failures, more so in light of COVID-19. In Philadelphia, as it is across the country, both the housing crisis and the global coronavirus pandemic disproportionately affect people of color.

As of today, applications for public housing in Philadelphia are closed. There are upwards of 40,000 people still on the waiting list, with an average wait time of 13 years, something that even PHA officials admit is difficult in light of their stated mission.

"“There’s so many abandoned homes and nobody works on them for years. Why not share them?"

And like many public services in the city, from trash collection to schools, COVID-19 has impeded the housing authority’s work. In many cases, they cannot do what’s necessary to bring these houses up to code.

For some in the community, limited resources for such a large group in need become, fundamentally, a question about fairness, as difficult as those conversations may be.

“We’re talking about trying to house people and there’s no fair way of doing a lot of things,” Arce said. “How do you take a group of people who are at Occupy and give them housing when there are so many other people, 40,000 people, who are still in need of housing? That’s a hard decision to make.”

And Arce understands making hard decisions and wanting to help those in need. When COVID-19 struck, her organization was tasked with helping to feed those in the community who couldn’t leave their homes due to the statewide stay-at-home orders. What began with 50 people is now a weekly drop-off to 270 community members in need — seniors, children, and persons with other limitations who can’t leave the house.

Fairness is at the center of this conversation, and the City’s housing crisis as a whole. Due to a declining population, tax delinquencies, and other issues, Philadelphia has amassed upwards of 40,000 abandoned properties over the past few decades. It’s more than enough to house the nearly 6,000 people who need it, according to Occupy activists, but far short of the 40,000 on PHA’s waiting list when those in disrepair are taken into consideration — and Occupy argues that the housing authority has allowed them to become unlivable on purpose.

For members of the Sharswood/Blumberg community and those representing them, this stalemate is about keeping the dialogue open and respecting the voices of those in need. As Brawner noted, he feels the PHA has been transparent throughout the past few years.

“There’s a difference between conversations and arguments,” he said. “This process has been mostly transparent to the people who were in the community. If you were a part of all of that — all of that — not just a piece of it, not the end. But if you were a part of all of that then yes, you have every right.”

“But if you were not, then you need to find somebody who was,” he continued.

For Laurel, though, she remains above the fray, focused on protecting her children. She needs a home, and she’ll do whatever it takes to provide for her family.

“There’s people that’s out here struggling,” she said. “There’s so many abandoned homes and nobody works on them for years. Why not share them?”

“Why not open them doors for us?” she added.

A veteran housing official speaks

In mid-July, Occupy PHA demonstrators gave notice to Philadelphia Housing Authority CEO Kelvin Jeremiah that he had three days to vacate his home. The action, a response to the City’s efforts to clear out the encampments on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and Ridge Avenue, was accompanied by sustained protest outside of his private residence.

“When I say everyday I mean every damn day,” Occupy PHA posted on Facebook in regards to how long they would continue to demonstrate in front of his house. “Dinner on the way!”

A veteran housing official, Jeremiah, began his career with the with the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination and did a tour with the New York City Housing Authority before finally landing in Philadelphia in 2011. After being appointed CEO and president of the agency in 2013, he was able to help bring the PHA back into local control within his first month on the job.

He remains a controversial figure in Philadelphia, although that’s due, in part, to the size and history of the organization he runs. Along with the day-to-day operations which he oversees, Jeremiah is tasked with making sure that the PHA operates within a proper regulatory framework. He administers the housing Choice Voucher Program formerly known as Section 8 public housing, and provides a host of social services to over 80,000 public housing residents.

“We have an annual budget that is federally funded for approximately $400 million dollars to provide housing subsidies under the Section 8 program,” Jeremiah said.

He’s also aware of the many charges and accusations that have been lobbied by Occupy PHA, and, according to Jeremiah, he shares some of their concerns. Like the activists themselves, Jeremiah says he struggles with the fact that the PHA waiting list is 40,000 applicants long and five to 10 years deep.

“We are federally funded [by] about 93 percent [and] the funding that we receive first and foremost goes towards supporting the people who are already on our various programs,” Jeremiah explained. “We don’t receive new money to expand the availability of affordable housing to address the incredible, incredible demand that we have, nor is the funding that we receive based on the demand that exists for affordable housing in the city.”

“I would love that,” he continued, “but unlike so many other public housing authorities across the country and in virtually every big city, we receive no funding from the city or state government. And so with the resources that we have we find creative ways to address the needs that exist.”

What many people might not know, said Jeremiah, is that the PHA provides over $40 million in subsidies to help people experiencing homelessness, people on the brink of homelessness, and people near joblessness. PHA also works with organizations like Esperanza and Project Home.

Like the activists themselves, Jeremiah says he struggles with the fact that the PHA waiting list is 40,000 applicants long and five to 10 years deep.

But, according to the activists at Occupy PHA, the City, along with the housing authority, is waging war on poor and working-class residents. The group claims that the PHA is seizing private homes and evicting tenants without court orders through the use of their private police force. They also assert that the agency backdates records so that they can sell properties to land developers and, claim that PHA ignores gun violence that occurs on their units.

Earlier this week, PHA officials and police officers raided two abandoned homes at North Philadelphia’s Peace Park, despite ongoing conversations with the group to allow them to restore the buildings. The housing authority later admitted that the raid was a mistake.

But, on the whole, Jeremiah insisted that his agency does things by the book, from evictions to record-keeping, to the actions of its small police force, which is tasked primarily with community relations.

And in response to some of the other accusations leveled at his agency, Jeremiah hoped to clear the air. For example, Occupy PHA has argued that the housing authority is spending $25 million on a parking garage in North Philadelphia, but Jeremiah said that’s not the full story.

“What is missed in that discussion is, one, the community asked us for a commercial corridor to help them,” he said, “with a commercial corridor that would bring a supermarket, that would have an urgent care, that would have retail and that would provide mixed-income, mixed-use development.”

“Where the encampment is right now is preventing us from doing exactly that,” he said. “Well, you’re sitting on a site that would provide a hundred units of housing.”

Jeremiah noted that PHA is called on to address the affordable housing crisis, the homelessness crisis, crime issues, and social and economic barriers their residents face. They’re all things he believes that PHA does well, though the Occupy movement disagrees.

One thing he was adamant about was that PHA’s policies are not racist or discriminatory, though detractors have said that about them.

“There is no other agency anywhere in this city that provides the support for Black and brown families the way we do,” he said.

Trending News