Race and exclusion in Philadelphia: Snapshots from the past 100 years

March 27, 2019

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

March 27, 2019

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

Editor’s note: Earlier this month Eric Hartman wrote a piece for Generocity that highlighted the gaps in Philly-region life expectancy differentials, where differences by neighborhood are larger than they are between Botswana (65.7 years) and Japan (83.7).

About the same time, his colleague Stephanie Keene was interviewed about her decarceration work and commitments by Black History Untold. She observed that, “It’s difficult because there’s an unlearning that we have to do. We have to examine why is that? How did we get there? I choose to believe that it’s not from a lack of love. I choose to believe it’s the result of conditioning, programming and structural racism that we have to unlearn.”

They wrote this guest post together. Because of its length, it will be published in two parts.

To unlearn, we must take the time to see the structural racism of our region in its specifics and particularities.

In the piece that follows, we share a non-exhaustive list of regional exclusion and racism, during the past 100 years, frequently backed by corporate and/or government authorities. That history helps explain how Philadelphia has developed considerable entrenched poverty, segregation, and related life expectancy gaps.

Before we begin with this century of lowlights, we want to emphasize that in the class we’re co-leading, we’re drawing heavily on Eve Tuck’s Suspending Damage and Adrienne Maree Brown’s Emergent Strategy. Both of these texts, in different ways, emphasize the importance of systems and structural thinking, while resisting structural determinism. The story below is not about what this region must become; rather, it is a realistic accounting of some of the historical and persistent structures we must overcome.

To dismantle those systems, we must do constant work to see them clearly — and we must always understand that justice, and specifically racial justice, will require decades of conscious effort to reimagine systems, far beyond what we have yet been able to achieve. It must be said: this is not about avoiding individual acts of racism (the barest of minimums), but redressing centuries of structured violence and exclusion and its contemporary manifestations.

The story below is not about what this region must become; rather, it is a realistic accounting of some of the historical and persistent structures we must overcome.

Philadelphia’s nearly 20-year life expectancy gap among neighborhoods correlates with racial demographics. Places that are high majority Black have lower life expectancies. Whiter places have higher life expectancies. What historical and current forces produce and reproduce this outcome?

First, Philadelphia is a city in the United States, so it is part of 400 years of inequality, during which only a few more than fifty years have seen the beginning of an effort to redress 350+ years of violent, state-sanctioned abuse, slavery, and murder. Second, though many white folks want to believe the “North is just better” narrative in The Green Book and elsewhere, Philadelphia’s unabashed racism is as real and recent as any other place in the country. Let’s just work in the historical present, starting when the oldest among us might have been alive — about 100 years ago — and walk it forward.

1910s and 20s

In May of 1916, the Pennsylvania Railroad began to offer free transportation north to southern Blacks willing to work for the railroad. Between the railroad and other industries, tens of thousands of Black people migrated to Philadelphia through the lure of work. As the Black population grew, Black residents purchased homes in traditionally white, largely Irish American neighborhoods. In July 1918 a white mob gathered outside the home of an African American woman, Adella Bond, who had just purchased her new home in the 2900 block of Ellsworth Street, in what’s now known as the Greys Ferry section of the city. A man threw a rock through Bond’s window. She responded with a revolver shot to his leg. White and Black Philadelphians then faced off in days of fighting that included some 5,000 residents. Roughly 60 Black men wound up in jail, while only three white men were arrested during the riots.

1930s

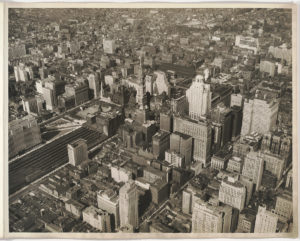

Neighborhood exclusion became more sophisticated in the ’30s. The process of drawing red lines around areas where lenders refused to make loans or made loans on less favorable terms —redlining — was developed by the Federal Housing Administration. In A Dream Deferred: PHL Redlining, Past, Present, Future, Tayyib Smith and Meegan Denenberg highlighted how race and policy shaped our local landscape. Racial discrimination in mortgage lending in the 1930s and the decades that followed continue to influence families’ and communities’ capacites to save and accumulate economic wealth through to today.

1940s

During the Second World War, Philadelphia played a vital role in industrial production. Yet, as detailed in Temple University’s Civil Rights in a Northern City, “when American unity abroad and at home was most crucial, hundreds of Philadelphia Transit Company employees went on strike to protest the promotion of eight black Philadelphia Transit Company employees to the position of trolley car driver.” A labor organization jeopardized industrial production during the war with Nazi Germany just because eight Black individuals were given a small opportunity.

1950s

Right up until the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education desegregation decision at the US Supreme Court, Philadelphia City School policies prevented sizable Black faculties from teaching any white children and Black principals from supervising white teachers. Following Brown v. Board, school integration began to pick up. Many white families responded by moving to the suburbs or enrolling in Catholic and other private schools.

One can imagine that not all of the movement to the suburbs was rooted in hate. The economy was booming; cars were suddenly accessible to a growing portion of the population. But Black families, unlike their white counterparts, were frequently denied the benefits of WW II service through the GI Bill and their real estate savings rates had already been undermined through redlining. Despite these forces, some Black families did move to the suburbs.

In 1957, William and Daisy Myers, along with their three children, became the first Black family to move into Levittown, PA, just 20 miles north of Philly. A ground-breaking documentary, Crisis in Levittown, chronicled the family’s experience of resistance to their purchase, their persistence, the eruption of violence, and cross-burnings in their yard. The Myers and their supporters persisted, and the family stayed in that community until William Myers received a job offer in Harrisburg four years later.

In Part II: The sixties, Rizzo, MOVE, the mass incarceration machine, and the work we need to do to move forward.

Trending News