Time is key: Applying a Black Quantum Futurist lens to understanding solutions to housing inequality

June 9, 2021

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

June 9, 2021

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

Disclosures

This guest column was written by Rasheedah Phillips, managing attorney for Housing Policy in the Housing Unit of Community Legal Services.Editor’s note: At the end of May we asked Rasheedah Phillips, housing lawyer, founder of the Afrofuturist Affair/Black Quantum Futurism and cofounder of Community Futures Lab, to write a guest column for us about futurism, ‘technologies of joy’ and equitable housing in Philadelphia. We’re delighted to present her deep dive into those topics here.

Housing, displacement, time, and the temporal domain of the future are inextricably linked.

Time inequities show up at every step of the processes of displacement resulting from urban redevelopment — from the short notice requirements, to the time required for families to vacate their homes, which is often severely out of line with the time needed to secure new housing.

It follows that preservation of affordable housing and prevention of displacement, such as for the residents of Sharswood, is inherently a time-based effort at every level.

As a legal services housing attorney, I work to preserve affordable housing for low-income Philadelphians. Some of my policy work in collaboration with community based partners and residents, has included working to extend the length of notice requirements for low-income tenants at risk of losing their homes, and keeping the housing affordable into the long term future by negotiating a “99 year ground lease” that will essentially work to keep a particular housing site affordable for that length of time.

We have collaboratively worked on efforts to increase access to tools to help communities plan for their long-term futures, such as working with residents of Sharswood to increase community engagement in the community planning and development process.

Through my afrofuturistic cultural work, I have developed the theory and practice of Black Quantum Futurism. In applying a Black Quantum Futurist lens to understanding solutions to housing inequality, I believe that temporal awareness and sense of time is key.

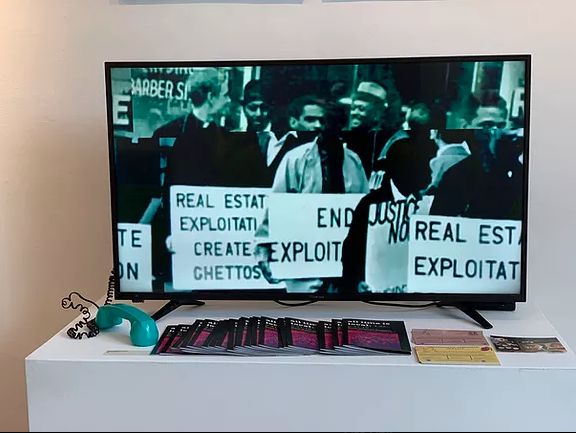

Part of Black Quantum Futurism’s exhibition “All Time is Local.” (Photo from blackquantumfuturism.com)

BQF calls for actively engaging temporalities and adopting alternative temporal orientations and frameworks, opening up access to the future. To quote Mark Rifkin, “the new time rebels advocate a radically different approach to temporality.”

Applying a Black quantum futurist lens to communal temporalities works to reappropriate time, stealing back time to actively create a vision of the future for marginalized people who are typically denied access to creative control over the temporal mode of the future, and redefining that future’s relationship to the past and present.

As Kodwo Eshun concludes in Further Considerations on Afrofuturism, “afrofuturism may be characterized as a program for recovering the histories of counter-futures created in a century hostile to Afrodiasporic projection and as a space within which the critical work of manufacturing tools capable of intervention within the current political dispensation may be undertaken.”

Using afrofuturism as a way to access alternative perspectives on what the future will look like is not only encouraging to people who have been given the message that they likely won’t survive to make it into “the future,” but it also comes with a whole visual and cultural language that posits joy and hope as technologies that allow Black people to shift the means of access to the future.

As Kevin Birth and other scholars have argued, “the dominant temporality associated with time as linear and consisting of uniform containers is disruptive to alternatives, including temporalities of hope.” The economic and capitalist futures constructed by government powers, as Birth puts it, “limits the imagination and provides an inescapable and nonnegotiable structure for the future.”

It is only when people feel they have a stake in a future that is non deterministic, not associated with economic gain, and rooted in community, can possibilities for hope, creative control, and meaningful access spring forward.

My collective lives in and focuses on North Philly as an active site of Black futurist liberation that has forged and reified its own temporality in the midst of hostile visions of the futures of the low-income, marginalized Black communities concentrated within its boundaries.

In a recent BQF exhibition called “All Time is Local” we consider time’s intimate relationship to space and locality through a text, object, and video installation. Including select pieces from our Dismantling the Master’s Clock, Temporal Disruptors, and Black Space Agency series, the works meditate on the complex, contested temporal and spatial legacies of historical, liberatory Black futurist projects based primarily in North Philly.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UmcXYrLcNGA]

Some of these projects, like Progress Aerospace Enterprises, have been all but forgotten, while others still stand and persist, such as Progress Plaza, Berean Church, and Zion Gardens. Others still, like Berean Institute, have monuments at the sites where they once stood, while other monuments and murals commemorating these legacies have been covered or removed by luxury and student housing.

In spite of the status of the physical remnants of many of these Black futurist projects, their implications stretch backward and forward in the afrofuturist timescapes undergirding North Philly. BQF works to recover and amplify the historical memory of these autonomous Black communal space-times embedded in North Philly.

One of the Black futurist projects we explore is Progress Aerospace Enterprises (PAE). Based in North Philadelphia during the 1960s, Rev. Leon H. Sullivan, a civil rights leader and minister at Philadelphia’s Zion Baptist Church, established PAE days after the death of Martin Luther King Jr.

PAE was one of the first Black-owned aerospace companies in the world. With the moon landing being seen as one of the ultimate milestones of progress of western society and a quintessential symbol of humankind’s arrival into “the future,” Sullivan stated in an interview that “when the first landing on the moon came, I wanted something there that a black man had made.”

PAE had strong connections to the Civil Rights and Black liberation movements, affordable housing, economic stability, the April 1968 passage of the Fair Housing Act, and the space race. Sullivan also founded the Zion Gardens Apartments affordable housing project with members of his church, purchasing the building from the owner after learning that Black applicants had been denied housing there based on their race.

He also organized boycotts, workers’ strikes, and community police boards. With members of his church, he founded Progress Plaza (the first Black owned supermarket plaza that still exists today), Progress Garment Factory, Opportunities Industrialization Center, Inc., Zion Investment Association, and other innovative organizations and programs around the country and world.

Throughout all of his organizations and at PAE in particular, Rev. Sullivan emphasized hiring of women and young, unskilled laborers and provided them with training opportunities and jobs in engineering and building parts for NASA and, controversially, weapons for war.

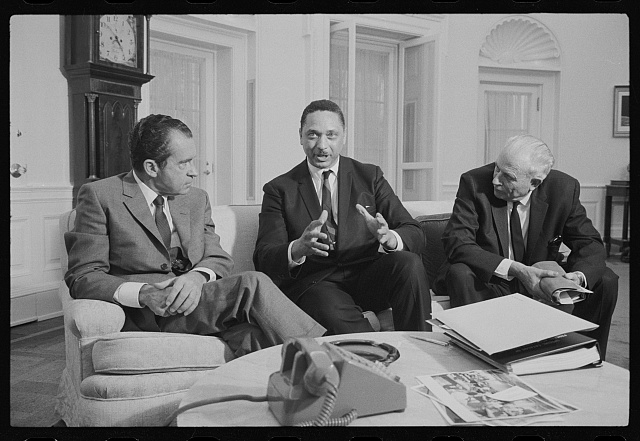

The Rev. Leon Sullivan, center, with President Richard Nixon in a photo by Marion Trikosko from March 25, 1969. (Photo from the Library of Congress digital archives; LC-DIG-ppmsca-56684)

Although Rev. Sullivan was a controversial figure, critiqued by anti-capitalists and the more radical Black liberation movements in Philadelphia as being respectable and pro-cop , his futurist vision of progress in the Progress Movement was nonetheless inclusive and innovative for its time.

His co-opting of the “progress” narrative and usage of the “future” in slogans were specific forms of temporal reclamation.

As Helga Nowotny notes in Time: The Modern and Postmodern Experience, “temporal control is symbolized by the idea of progress, of economic boom.”

Sullivan seemed to grasp the close associations between temporal control, sustainable Black communities existing within the American imperialist project, and the notion of linear progress well. The technology built at PAE and through other Rev. Sullivan projects seemingly allowed for a hacking into future histories where Black people had already been largely erased — such as in the space race — and helped to ensure our appearances in those histories as they play out on the linear, progressive timeline.

Or, as Eshun puts it, “chronopolitically speaking, these revisionist historicities may be understood as a series of powerful competing futures that infiltrate the present at different rates.”

During that decade, the Civil Rights and Black Liberation movements and space race would collide, with a lot of resistance to the space race from the Black community, such as the Poor People’s March at Cape Canaveral. Black leaders across wide and varying political stances from Martin Luther King Jr. to Eldridge Cleaver commented on the race to land on the moon, juxtaposed to the neocolonialism and urban renewal causing displacement of entire Black communities.

In a 1966 speech Dr. King remarked that “there is a striking absurdity in committing billions to reach the moon where no people live…while the densely populated slums are allocated miniscule appropriations,”and ended his speech questioning “on what scale of values is this a program of progress?” MLK could not determine a sense of progress where Black people had not yet achieved racial justice and social equity.

Reflecting on the archives of Black newspapers and magazines like Jet and Ebony, and even national news publications reveals widespread critiques of the lack of diversity in NASA employees, and the destruction and displacement of Black communities in order to build subsidized housing for NASA employees. Partly in response to such critiques, NASA created programs that designed and utilized spaceship materials in “urban” housing, as well as campaigns to increase diversity in hiring.

Meanwhile, destruction, segregation, and displacement of Black communities across the United States (the space race on the ground) led to riots and uprisings around the country during the 1960s, including North Philly. Columbia Avenue, now known as Cecil B. Moore Avenue after the late Philadelphia civil rights attorney and activist, was the site of race riots and uprisings in 1964 that destroyed a once vibrant, multiethnic community with a strong economic base — the reverberations of which continue to echo throughout that community.

Part of Black Quantum Futurism’s exhibition “All Time is Local.” (Photo from blackquantumfuturism.com)

In present day, gentrification, racialized segregation, and targeted disinvestment has disrupted the landscape, vibrancy, and texture of the neighborhood, forcing its memories and residents to the edges of the city.

Housing and cultural displacement are usually framed in terms of spatial inequality and displacement or erasure from location.

However, hierarchies of time, inequitable time distribution, and uneven access to safe and healthy futures inform intergenerational poverty in marginalized communities in some of the same ways that monetary wealth passes between generations in privileged communities.

Sociologist Jeremy Rifkin says that “temporal deprivation is built into the time frame of every society,” where people living in poverty are “temporally poor as well as materially poor.” Inevitably, marginalized Black communities are disproportionately impacted by both material, spatial, and temporal inequalities in a linear progressive society.

The implications of time and of space in gentrification, displacement, and redevelopment are integrated into the pre-established temporal dynamics of the impacted community, layered over and within the communal historical memory and the shared idea of the future(s) of that community.

Nested within those layers are individual, subjective temporalities and the lived realities of the residents, often at odds with the linear, mechanical model of time on which and its external spatial-temporal constructs are etched.

But as Giordano Nanni points out in The Colonisation of Time, “time has long played a role as one of the channels through which defiance towards established order can be manifested.” By exploiting those temporal tensions, there are several opportunities to develop practical strategies for achieving Black temporal autonomy and spatial agency.

Some of these strategies including unearthing afro/retrofuturist technologies and quantum time capsules buried by our forebears.

Project

Philafuturism, civic innovation and tactical community techTrending News