Can financial literacy solve Philly’s poverty problem?

May 14, 2018

Category: Feature, Featured, Long, Method

May 14, 2018

Category: Feature, Featured, Long, Method

First, an economics lesson.

In a capitalist society, income comes primarily from two sources: wages or investments.

It’s jobs, not investments, that have been the primary source of most Americans’ economic well-being. However, the 21st century has ushered in a new economic reality.

“Even with more jobs and lower unemployment, the poverty rate stood at nearly 26 percent, and Philadelphia retained its title as the poorest of America’s 10 most populous cities,” gloomily summed the Pew Charitable Trusts’ most recent “State of the City” report; that number disproportionately represents people of color.

Now, a social policy question: Could increasing financial literacy levels of those already in poverty help alleviate poverty?

This debate began in earnest in the aftermath of the Great Recession. In its 2015 report “Financial Capability and Asset Building for All,” American Academy of Social Work & Social Welfare (AASWSW) named building financial capability as one of social work’s 12 “grand challenges” because lack of financial knowledge is a key contributor to poverty.

And research from Fortune 100 financial services org TIAA-CREF showed the low levels of financial literacy were associated with more borrowing, less wealth, higher financial product fees, less investment activity, debt problems and a decreased ability to comprehend the terms of their loans.

"Financial competence, combined with access to opportunities to generate greater wealth, is necessary for low-income families to transition from struggling to thriving."

“Financial literacy is an essential catalyst for economic mobility and advancement,” said Rev. Luis Cortés, Jr., founding president and CEO of Esperanza, a faith-based nonprofit serving Philadelphia’s Hispanic community, including through housing counseling.

“Low-income families must be assisted in building their financial assets — by developing greater cash flow, savings, and stronger credit — and taught to manage those assets for the future,” he said. “This skill set not only allows families to move from a position of instability to stability, but it also equips our community’s children at an early age, so they can avoid the challenges their parents may have faced. Financial competence, combined with access to opportunities to generate greater wealth, is necessary for low-income families to transition from struggling to thriving.”

But is literacy enough to cause the behavioral change necessary to make a difference is a person’s life?

“Financial empowerment, not literacy, is what I would call it, and financial empowerment by itself will not alleviate poverty,” said Dr. Mariana Chilton, director of Drexel University’s Center for Hunger-Free Communities. “It needs to be built into other types of programming.”

Chilton is building financial empowerment into a trauma-informed peer support program for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) recipients called the Building Wealth and Health Network; TANF is the federal cash welfare system and is designed to lead welfare recipients to financial self-sufficiency. A study in the May 2018 issue of Journal of Child and Family Studies to which Chilton contributed found that “financial empowerment education with trauma-informed peer support is more effective than standard TANF programming at improving behavioral health, reducing hardship, and increasing income.”

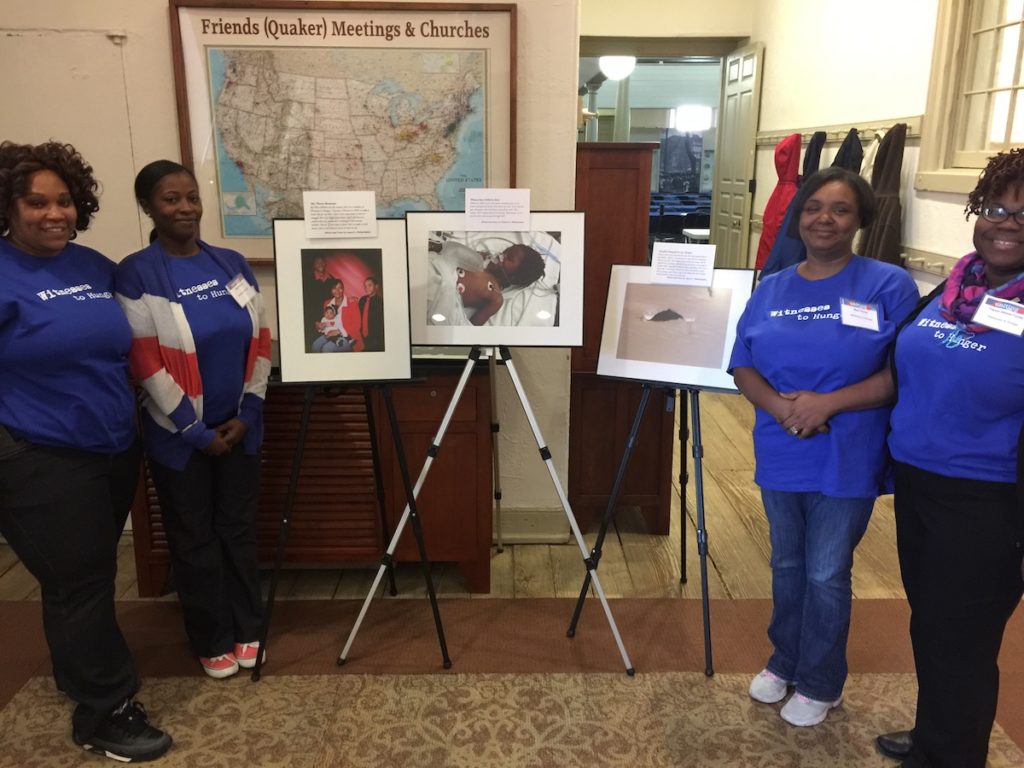

Center for Hunger-Free Communities’ Witnesses to Hunger program, which uses first-person storytelling, including photography, to affect policy. (Courtesy photo)

Wharton School professor Dr. Keith W. Weigelt, founder of Bridges to Wealth (or Bridges2Wealth), agreed that financial literacy alone “doesn’t change behavior” — but he argued that it is essential to increase wealth, not income. “Wealth is a function of how you invest, not how much you make.”

Bridges2Wealth is an intergenerational program that works in collaboration with community partners, especially schools, to offer a six-hour financial planning course and social support through peer meetings. The meetings do two things, Weigelt said: Further people’s knowledge and, perhaps more importantly, foster social connections based on investing.

Those experiencing poverty are easily exploited, he said with evident frustration, because they lack basic investment knowledge: “Why accept 0.5 percent [interest rate] from a bank when historically the stock market returns eight percent annually?”

Financial empowerment and wealth building are micro-level fixes for a macro-level problem.

Chilton acknowledged that financial empowerment and wealth building are micro-level fixes for a macro-level problem.

“Financial empowerment will not make a huge difference in the large scale,” she said. “In other words, it won’t help thousands [or] millions of people.”

The international Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) posits that financial education should start as early as possible. According to the Council for Economic Education, the number of states requiring high school-level personal finance education increased to 23 in 2016.

Pennsylvania is not included in that number, though economic education is included in some K-12 standards, which are implemented by district.

Champlain College’s Center for Financial Literacy last year gave Pennsylvania an F in its “Report on National High School Financial Literacy” for not requiring financial literacy instruction in its 500 school districts; only 15 percent do, not including Philadelphia.

That likely means the typical Philadelphia student will graduate next month and join the ranks of most Americans who earn poor grades on their knowledge of personal finance.

One possible solution?

“A revolutionary act,” said Chilton, “would be to ensure that women of color who have low incomes can own the bank — the instrument of wealth building — and thus build their wealth while helping others to build their businesses, improve their homes and invest in their kids.”

Project

Broke in PhillyTrending News