The protest encampments — and the housing crisis they represent — aren’t going away

August 19, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

August 19, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

The mood among unsheltered Philadelphians living at two protest camps on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and Ridge Avenue turned fearful Monday as city officials posted notice that residents must evacuate the encampments by Tuesday morning.

“People are trying to prepare for whatever might ensue,” said Indigo, a 20-year-old Temple University student and housing activist who’s been instrumental at keeping the camp’s residents safe over the past few months.

“We are calling on our community to come and rally with us and stand with us [Tuesday],” Indigo said. ““People are scared.”

Indigo at the donation station at camp James Talib-Dean on the Parkway. (Photo by Brandon Dorfman).”

Threats to close the encampments, including posted notices, are nothing new for the residents of the months-old protest encampments. What is different this time around, and what makes the situation so dire for the people experiencing homelessness in Philadelphia, is the change in rhetoric that accompanied the city’s eviction notices.

On Monday morning, City officials posted notice that residents must clear camp James Talib-Dean on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and camp Teddy on Ridge Avenue, after declaring that the negotiations with Occupy PHA, the Workers Revolutionary Collective, and other housing rights groups representing the protestors were at an impenetrable standstill. Mayor Jim Kenney’s office released a statement calling further discussions with activists “fruitless.”

Activists not only disagreed with that assessment but see the statements released by the Mayor’s office and the Philadelphia Housing Authority as a full-on propaganda assault meant to discredit their movement.

“The continued shifting of camp leaders’ demands, and the fact that some of their repeated demands are out of the City’s control, or unachievable in the time frame that they demand, all contribute to this difficult decision,” Kenney said in the statement that was reiterated by Mike Dunn, the City’s senior deputy communications director, when Generocity spoke to him.

According to the Mayor’s statement, the City, along with the Philadelphia Housing Authority, agreed to several “concrete” actions, including the creation of sanctioned encampments, two COVID-19 prevention sites with a total of 260 beds, and a moratorium on sales of PHA properties. In total, the Mayor’s statement outlined 10 concessions offered to activists, which according to Dunn, is in addition to the shelters, residential treatments, and other housing options such as hotel rooms with private bathrooms at the COVID Prevention Spaces the City has already provided to at least 80 residents of the encampments.

As per both the Mayor’s statement and Dunn, activists agreed to write up the concessions following a verbal commitment from the city last week, only to present a document that did not accurately reflect the negotiations, and accused activists of negotiating in bad faith.

Camp activists with direct knowledge of the negotiations told Generocity that the City’s position on the demonstrations is more public relations than principle.

According to Sterling Johnson, one of the dissidents who’s come to the table for Philadelphia’s unhoused residents, city officials offered a quid pro quo of sorts. Local squatters under Occupy PHA’s protection would be spared eviction, Johnson said, while the rest of the city’s public housing residents would be given no such guarantee, or worse, would be subject to illegal evictions by the PHA. The protestors rejected that offer outright, believing that all people should be afforded due process when it comes to evictions.

"The main sticking point is about (the PHA), about how they should not be dragging people out of their homes at night."

“The main sticking point,” Johnson said, “is about [the PHA], about how they should not be dragging people out of their homes at night.”

Activists say they haven’t seen any tangible progress over the past few months. Johnson said that the city hasn’t offered a sanctioned encampment — which the two sides discussed for emergency periods — and that the proposed use of Emergency Solutions Grant funds to aid camp residents hasn’t come to fruition either. LGBTQIA and COVID-19 housing has also been a non-starter, or in the case of the latter, severely lacking, according to several activists.

Further, the activists believe that the City’s public relations efforts have intended to discredit them and the residents of the encampments.

“They’re going to say these people are drug dealers,” said Johnson, who, along with other demonstrators, has heard arguments that their group doesn’t represent the neighborhoods they now inhabit. “[We represent] Queer people and Femmes and Black people and Indigenous people but we also represent all the unhoused people across the city.”

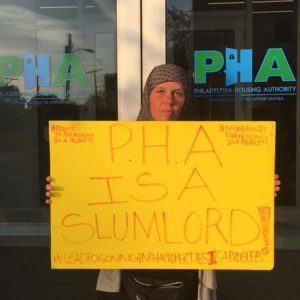

Housing activist and Occupy PHA founder Jennifer Bennetch pulls no punches and calls the city’s and PHA’s actions “disgusting.”

Bennetch has not only been a leader in helping Philadelphia’s unhoused population find safety at the encampments this summer, but she’s also been instrumental in coordinating the largest takeover of abandoned public housing properties in the nation, placing over 40 people in PHA homes over the past few months.

Bennetch believes that the city made up its mind months ago about what to do with the encampments and that what they’re offering now are breadcrumbs.

“[The city] is offering things they had already planned and offering it as a concession to us, like a Tiny Home Village in 2021,” Bennetch said. “These people are homeless right now. Building new affordable housing [when] there’s thousands of vacant Housing Authority city-owned properties all over the place? These are not solutions for now.”

She feels that the city isn’t negotiating in good faith, especially when threatening to kick people out of the camps with no place else to go. “I can’t tell these people to leave [the camps], they wouldn’t listen to me if I tried,” she added.

Bennetch and other activists have not only accused the PHA of misrepresenting the Housing Authority’s position in these ongoing disputes, but of also promoting a false perception of local communities, like Sharswood, that are caught in the middle of it. They point to neighborhood leaders who have spoken out against the encampments, such as Darnetta Arce, a Sharswood resident who serves as the executive director of the Brewerytown Sharswood Community Civic Association, as well as Asia Coney, and question their ties to the PHA.

Arce’s husband has worked for the PHA in the past, and she’s also bought and sold a PHA property according to records; Coney is on the PHA Board of Commissioners.

PHA CEO and President Kelvin Jeremiah calls those accusations “foolish.”

In an interview with Generocity, he stated that the PHA employs upwards of 1,400 people, all of whom are required to live within the city limits. “There are going to be relationships,” said Jeremiah, “relationships that sometimes are very nuanced, but relationships that by themselves are not improper or illegal.”

Jeremiah said that Arce’s husband has had two stints with the PHA, including his current position, but according to him, that doesn’t take away from the fact that she’s been a 20-year resident of Sharswood who wants what is best for the neighborhood. Per Jeremiah, Coney represents one of the longest-standing resident advisory organizations in the country, started in 1967, which works for resident representation in public housing. Her role with the PHA is as a resident advocate.

Jeremiah, whose agency collaborated with the Mayor’s office on Monday’s statement and closure notices, insists that the PHA supports the needs of the encampment residents and the demonstrators’ right to protest. But he also has a responsibility towards public housing residents all across Philadelphia — including Sharswood, where he has repeatedly insisted, the protest camps are blocking PHA construction on neighborhood necessities such as a grocery store, urgent care, and more. The neighborhood has been a food desert for decades.

More importantly, the PHA president said that activist demands would require PHA to violate federal policy.

“One of the expectations or demands rather the encampment leaders had was that PHA immediately convey to them scattered sites,” Jeremiah said. “We cannot convey our scattered sites. Our properties are held in trust to the Federal Government. So I cannot sell or give away PHA properties without federal approval.”

“We believe that it would have been unfair, illegal, in fact, to occupy a PHA unit without at least going into the unit to have it inspected before every occupancy or re-occupancy,” he added.

With upwards of 40,000 people on the now-closed PHA waiting list, Jeremiah also believes it’s unfair for people to jump in front of the line, which is what he portrays the Occupy PHA movement doing. Housing activists in the city argue that there are more than enough abandoned properties to solve the current crisis, but, according to Jeremiah, the solution isn’t so simple.

“It’s a question of the alignment of resources from the city the state and the federal government,” he said.

In a recent op-ed for WHYY, Jeremiah pressed activists to push for a legislative solution.

Speaking with Generocity, he specifically mentioned housing trust fund legislation proposed by City Councilwoman María Quiñones Sánchez and the still-languishing HEROES Act that’s sitting on Mitch McConnell’s desk. Those, he said, would have a direct bearing on the PHA’s ability to obtain resources that would add more units of affordable housing in Philadelphia, and provide hundreds of millions of dollars in additional funding to increase Section 8 housing, respectively.

“We remain hopeful that with the posting today at the encampment leaders will recognize our need to find and forge a new way forward,” Jeremiah said on Monday. “I remain open to working with them.”

In an email sent on Monday, Dunn said that the City was anticipating that things would go smoothly on Tuesday. “We strongly believe that those in the camp will voluntarily decamp, and avail themselves of the services being offered,” he said, noting that outreach workers had been offering services to residents and would continue to do so throughout the process. He stressed that the City would make every effort to help people experiencing homelessness at the camp connect to services, leave voluntarily, and find storage for their possessions.

Meanwhile, Councilmembers Jamie Gauthier and Kendra Brooks sent Mayor Kenney a letter on Monday, urging the City to “cease its plans to clear the two encampments tomorrow morning and return to the negotiating table as soon as possible.”

.@KendraPHL and I have asked @PhillyMayor to cease plans to clear the encampments tomorrow, and return to the negotiating table ASAP.

Dispersing these residents with just a day’s notice isn't a solution. It will only make securing housing for those who need it more challenging. pic.twitter.com/TOjXHIkceX

— Councilmember Jamie Gauthier (@CouncilmemberJG) August 17, 2020

Still, hope was in short supply at the camps on Monday evening. Activists and camp residents called for all hands on deck Monday night, ready to stand their ground and fight. Bennetch said she was looking for new spaces should things not go their way. No one was prepared to predict the future.

At camp Teddy where, per Indigo, over half of the residents are over the age of 55, many didn’t know what to do. “We have one resident there who I believe is 82 or 83, her name is Dolores, she’s very scared,” Indigo said. “Everyone is. These sweeps usually end in our belongings being trashed.”

But on Tuesday morning, as activists gathered their troops preparing for the worst, there was a reprieve thanks to a last-minute injunction filed in federal court.

“Leadership from the encampment requested that I file the TRO/Injunction,” Michael Huff, a lawyer and activist who practices primarily criminal defense and civil law, said via email. “With advice from the National Law Center form Homelessness and Poverty, we filed yesterday.”

“The federal judge is revisiting the request for an TRO/Injunction on Thursday at 10 am.,” Huff told Generocity on Tuesday night. “We will present testimony from individuals who reside in the encampment. I hope the City calls witness explain where they will be relocated and how their belongings will be preserved.”

For many of those in Philadelphia who are experiencing homelessness or have a unstable housing situation, uncertainty and a sense of vulnerability is nothing new.

“Displacement is really what with drives crime,” Indigo said. “It drives poverty, it drives [challenges to] mental health and stability. It drives infection. Displacement is disease.”

“Housing people, that’s the cure,” they said.

Trending News