Beyond the promotora model: These projects are focused on immigrant wellness in culturally distinct ways

July 16, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

July 16, 2020

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

Disclosures

Editor's note: You are free to republish this article both online and in print under a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license, provided you do not edit the piece, make sure to attribute the author, mention that the article was originally published at Generocity, and link back to the original post.Updates

Updated to correct a timeline mistake as well a an incorrect acronym in the Intercultural Wellness Program entry. (07/17/20 at 3:35 p.m.)Lea este artículo en español.

The last piece in Generocity‘s series about the promotora model of community-led wellness and advocacy, looks at other community-led models that are operating in Philadelphia.

Just as the promotora model’s effectiveness stems from its specifically Latin American and Latin American immigrant context, the following four project models are community-led efforts that respond to the specific cultural context of distinct immigrant communities. Funded by the Scattergood Foundation, the projects focus primarily on wellness needs within the African, Chinese and Korean immigrant communities, and one of the projects is tied to a neighborhood religious institution and is shaped by members of the multiple immigrant groups that reside in the neighborhood.

There are significant differences between these and the promotora model, but also significant similarities.

Intercultural Wellness Program

Manuel Portillo, director of community engagement at the Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians, spoke with Generocity about the Intercultural Wellness Program (IWP) — a joint project between the Welcoming Center and the African Family Health Organization (AFAHO).

The program is for immigrants and refugees from Africa, the Caribbean, Latin America, and Southeast Asia who want to support their community in terms of wellness, stress management, and utilizing coping mechanisms to address the challenges they face in Philadelphia.

“These are two distinct organizations; however, we come together because we found common ground. Welcoming Center has expertise in developing successful strategies for immigrants to integrate into the economy and social life of the city. AFAHO is an expert in offering health services to African and Caribbean communities in our city,” Portillo said.

The program’s goal is to help recently arrived immigrants develop skills, knowledge and relationships that can be instrumental in how they help themselves and their community. Portillo said they are currently working on implementing an initiative within the program which will focus on addressing behavioral health in local communities from a more grassroots approach.

“We started [that] about two months ago and only held one training session. Due to the pandemic, we had to put it on hold; now we are coming back to it, adapting to the new situation,” he said. “We had to redesign the program to make sure it works under the current circumstances.”

This wellness program aims to help with the oppressive language of mental health in the immigrant community.

“We want to learn from people and develop a new language that reflects the understanding and the reality of immigrants in Philadelphia. We know it is a resource. The traditional clinical approach to behavioral health has little impact in immigrant communities. At a very personal level, I do not believe it works,” he added.

If African immigrants do not want to participate in anything that is about mental health, how does IWP reach them?

“We take a listening approach and look at communities as creators of content and knowledge. Communities have a lot of experience, understanding and information and we want to tap into that and learn from it,” Portillo said. “We want the communities to define what wellness is for them and not go by the academic definition of wellness.”

Chinese Immigrant Family Wellness Program

Esther Hio-Tong Castillo is the project manager of Chinese Immigrant Family Wellness Program (CIFWP), a collaboration between the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation-PCDC and Hall-Mercer.

CIFWP started its work at the beginning of 2020. The plan was to create focus groups to find out the needs for mental wellness in the Chinese immigrant community.

“Mental health is a taboo topic for a lot of Chinese people,” Castillo said. “We spent time figuring out what would be the best language, how do we do the translation, whether or not we want to use the word ‘mental’. In February, we were going to do the focus groups and then COVID-19 hit.

“So all those plans had to be thrown out of the window. We were kind of scrambling, just like everybody else,” she said.

In March, CIFWP switched its focus to an online survey. “In focus groups, you can have more open-ended questions, the conversation will be more organic and in surveys, more restricted,” Castillo said. “We were lucky that we got more than 80 surveys back to figure out what the needs are. It included open-ended questions.”

CIFWP found out whether people would be comfortable joining online virtual workshops and if they were, what kind of technical support they would need and what topics they would be interested in.

In April and May, CIFWP started weekly workshops both in Cantonese and Mandarin.

They heard concerns from parents dealing with stress — for those with older children already in college, the pandemic was hard to handle. For parents with younger kids, many had difficulty with the switch to online learning. Castillo said with language barriers that became even harder.

“Those stressors have made mental wellness decline for a lot of our clients,” she said, “so we decided to gear the workshops to parents,” she added.

CIFWP also holds an English wellness workshop every Thursday for the youth. “A lot are preparing for tests, so [CIFWP] also provides homework support and mental wellness support. Also, a career series to help those who are in high school or graduating seniors to think about what college life is like and their future careers,” Castillo said.

CIFWP relies on people’s goodwill and generosity to volunteer their time and knowledge. For the workshops, the organization had a professional psychologist who volunteered her time and expertise to develop the content with Castillo (Castillo is a sociologist). The organization also has student volunteers.

In the first week of the workshops, there were only four or five participants, but those numbers have increased significantly. “Last week in the Cantonese workshop, we had 17 participants and in the Mandarin workshop, we had 21,” Castillo said. “I regularly receive text messages from [participants] saying how useful it is and they learned a lot, especially the communication with children workshop, to alleviate tensions that exist in the family. It is growing and quickly. I think it will continue to grow.”

The Mind, Body, Spirit and Space Initiative

Clara Jerez , part of The Aquinas Center staff, oversees the organization’s Mind, Body, Spirit, and Space Initiative.

“Spiritual life and mental wellbeing are an essential part of what we do at [the center and] St. Thomas Aquinas Parish,” Jerez said. “We offer a helping hand and through our programs, we empower immigrant families and individuals to thrive under any circumstances.”

We understand the impact of COVID-19 and the extensive damage it is creating both to the physical and mental wellbeing of immigrant communities and especially among our Latino and Asian communities,” she added. “As an organization rooted in the community, we have become a safe place for [community members] to reach out when some essential need arises. Our parish, located where multiple immigrant communities live, is committed to supporting them.”

Many of the components of the initiatives work before and during COVID-19 targets the social needs of the members of the immediate community. “Beyond spiritual and mental help, we also offer a place for worship, in addition to … our multiple areas of service including education, social services, food security, and childcare,” Jerez said. “We rely on members of the community as volunteers. Many times, we are serving as mentors, coaches, or guides to help the individual in any aspect of their situation.”

One of the main pivots during the COVID-19 emergency has been keeping the community together and informed. The Center has provided spaces for people to talk and ask questions.

“We have reached out to the community with a space for prayer in different languages. Praying for the sick, for the deceased, and for the individual intentions and connecting them to the word of God has been essential for the community during this difficult time,” Jerez said. In addition, the Center created a virtual office where people can call in and ask questions.

“It has been an outlet to the group to talk about their situation, the impact of the virus, family life and children’s problems. It has also served as a support group. ESL online, a youth group in Indonesian, among others, are the programs that we have kept going virtually,” she said.

According to Jerez, the Center has also been able to provide economic support for some families in addition to being an information outlet. “Giving them all of the resources available to be able to cope with these difficult circumstances,” she said, “but always with a message of hope.”

Korean American Association of Greater Philadelphia

When the Korean American Senior Citizen School received funding from the Scattergood Foundation’s Community Wellness Fund, the support acknowledged the project’s importance in keeping seniors healthy and connecting by offering them healthy activities with a strong grounding in Korean culture.

But that is just one program of the Korean American Association of Greater Philadelphia (KAAGP), said the organization’s president, Sharon Hartz, and when the pandemic hit, the KAAGP had the task of not only getting all 78 of its community leaders on the same page, but also shaping the pivot some of its committees would make in response to COVID-19.

Hartz said members of the association started social distancing back in March, and had to figure out how to get information out as soon as it became available, because their communications reach thousands of community members who rely on these announcements — especially seniors who have a language barrier and are vulnerable and at home.

This communication effort takes place via texts from mobile devices. With 78 community leaders, each is connected to more than 50 people, so they have a total reach of 10,000 people. And though the process was established in response to COVID-19, the association found it was useful during the civil unrest that took place in the city after the protests about George Floyd‘s killing by police.

Some 60 Korean business were impacted by the looting. “This is a devastating situation for many of Korean small business owners,” Hartz said when Generocity spoke to her shortly after May 31. “KAAGP officers and volunteers are trying find ways to assist with all the resources from different entities [within the association].”

The weekend that the looting took place, KAAGP leaders sent information via their group texts and Hartz estimates that ten or twenty thousand people heard about what happened from them.

She explained how this informative “texting tree” works when imparting information about the looting or about COVID-19 impacts: “Ten people are working to get resources from mainstream leadership and daily reporting is delivered through that platform of communication. Korean online newspapers also work with us and they send electronic information daily.”

When Trump started calling COVID-19 “the Chinese virus,” members of the Korean community wanted to come together and do something collectively.

About 12 weeks ago, KAAGP embarked upon a community mask-making campaign.

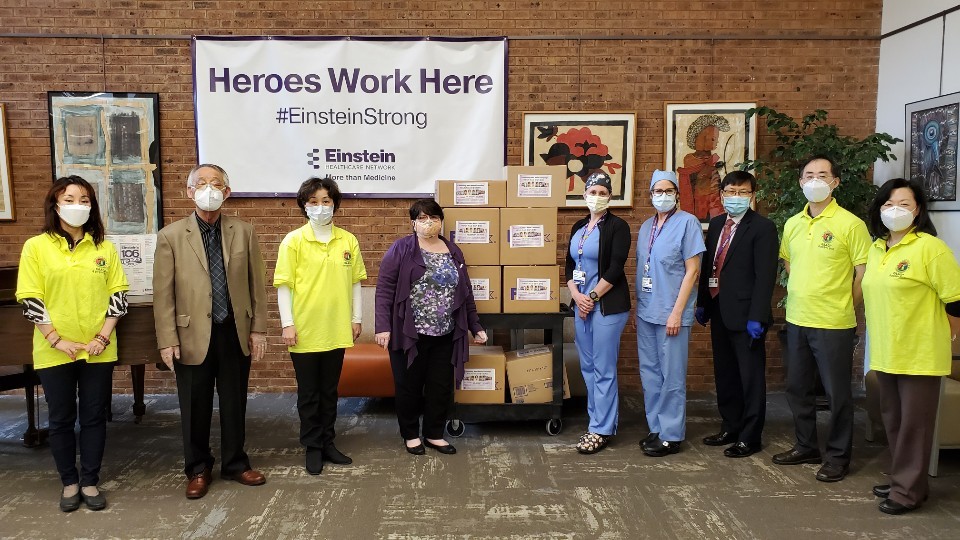

“Korean dry cleaners are all closed,” Hartz said. “We started to make the masks behind closed businesses. We came up with the idea to contribute and get donations. After 10 weeks, about 10 different Korean organizations were working together — [to make and secure] disposable, surgical, N95 and handmade masks. We contributed 20,000 masks to local hospitals, nursing homes and police stations.”

The Korean American Association of Greater Philadelphia donates not only purchased masks to local hospitals, but also those made by community members working in closed Korean dry cleaning stores. (Courtesy photo)

Forty volunteers were involved with cutting materials, making masks, and delivering them. “So, great teamwork,” Hartz said. “We are getting monetary donations as well as actual surgical masks or N-95. We got engaged with Chinese businesses and they bring the food [for us] to deliver together.”

Like the New Sanctuary Movement promotoras, KAAGP members have utilized phone banking to keep abreast of their community and to help people acclimate to outreach via the internet, and have started an emergency relief fund.

“A lot of [first generation] people are not using the internet,” Hartz said. “Because of the pandemic, they were not able to come out to our building to get services, especially seniors. We started sending them information and video clips; we made phone calls to give them instructions how to get it done. We made about 3,000 phone calls.”

In terms of the relief fund, she said everyone is pitching in time and expertise. “One community leader donated $10,000 to start, to help people who didn’t get government funds,” Hartz said. “We noticed there are a lot of people struggling financially, with rentals and lacking paperwork, they cannot even apply for it. We started helping them, building up their funds. We plan to give out a few hundred dollars each to 50 people.”

“Everybody has the same idea,” she said, “We need to help one another.”

Project

COVID-19 coverageTrending News