Funding the COVID-19 recovery in Philly: Tracing the lessons to date

September 3, 2020

Category: Featured, Funding, Long

September 3, 2020

Category: Featured, Funding, Long

Few countries, the United States not among them, paid attention when the United Nation’s World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency January 30.

Six months ago the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the first COVID-19 death in the United States. Since then the fast-moving pandemic has morphed into the country’s worst health nightmare in a century. More than six million Americans have been infected with the coronavirus. More than 185,000 Americans have died — almost 1,800 of them in Philadelphia (as of September 2, 2020).

With the health crisis has come economic collapse as state governments shuttered their economies to stem the transmission of the disease. Pennsylvanians faced one of the country’s most severe shutdowns as Gov. Tom Wolf eschewed Trump administration closure guidelines and closed all non-essential businesses March 18. The state entered the green phase of reopening July 3 but by then unemployment had skyrocketed and the economic results are still being likened to the Great Depression of the 1930s.

According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, in February, 800,000 workers were reporting layoffs. In June, the number had skyrocketed to 10.6 million workers. Currently, the country is hemorrhaging about one million jobs a week. According to the U.S Census Bureau’s latest U.S. Household Pulse Survey, of the 5 million residents in the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Camden area about half have experienced some employment income loss.

The federal, state, and local governments have been providing funds to alleviate the trauma, most notably the $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act which was designed to help unemployed workers, small businesses, and industries adversely affected by the pandemic. The act developed the $150 billion Coronavirus Relief Fund for states, and of that Pennsylvania received $4.9 billion and Philadelphia received $1 billion.

The CARES Act also created the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program which provided up to 39 weeks of unemployment benefits to people who were not eligible for regular unemployment compensation and the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation program which provided an additional $600 per week but ended in July.

"Given the scale of harm, we are going to require smarter, more coordinated funding."

Demand on the area’s nonprofits escalated as people were hit with food insecurity, housing instability, childcare concerns, unemployment, and health problems. The media wrote story after story of desperate families seeking help from local human services agencies who themselves were reeling from the economic catastrophe.

“The nonprofits that are hardest hit by COVID-19 are those with slim margins between revenue and expense and those dependent on government funding and reimbursements for their services,” wrote Sidney R. Hargro, president of Philanthropy Network Greater Philadelphia in a March blog post.

The philanthropic community responded by creating COVID-19 relief funds to provide resources to vulnerable nonprofits. One of the first relief funds to be established was the Bucks County COVID-19 Recovery Fund which started grantmaking in March after receiving $25,000 each from the United Way of Bucks County and Penn Community Bank. Since its inception that fund has raised $280,000 and given 52 grants to local nonprofits, such as $17,400 to the Network of Victim Assistance (NOVA) for computer and video equipment to allow staff to continue meeting with clients safely, as well as enhanced cleaning services.

The City of Philadelphia, Philadelphia Foundation and the United Way of Greater Philadelphia and Southern New Jersey joined forces to created the PHL COVID-19 Fund in March. In four months, they raised $17.5 million from 8,500 donors and provided much needed grants to 500 regional nonprofits.

Early on in the crisis, Hargro wrote on his blog that “COVID-19 will test our leadership mettle and pragmatic capacity to operationalize the notion that ‘we are all in this thing together.’”

He added that once the pandemic was ended, nonprofits would be graded on their ability to listen to the plight of nonprofits regarding recovery grantmaking process, streamline administrative processes, fund general operating and not project support, advocate for governmental policies that are nonprofit-centric, and collaborate with other funders

Staff at the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for High Impact Philanthropy (CHIP) has started the crisis grantmaking evaluation and spent the summer collecting grant award data from 13 COVID-19 response funds in the Delaware Valley. CHIP’s effort has been supported by the William Penn Foundation and Philanthropy Network Greater Philadelphia.

Together the funds represent $40 million of crisis grant awards in southeastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey. CHIP’s ultimate goal is to determine the best crisis funding practices. “We need to know what are the needs that the shared funds are addressing? Given the scale of harm, we are going to require smarter, more coordinated funding and this COVID-19 dashboard will enable that. It will make philanthropy more effective and efficient,” Executive Director Kat Rosqueta told Generocity.

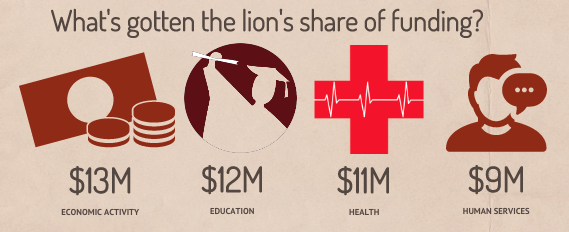

While they will not release their lessons learned until a September 29 webinar at noon — which is open to the public — they have created the Regional COVID Response Dashboard which shows how the grant money has been dispersed so far. The lion’s share of the funds has gone to the areas of largest community need — economic activity ($13 million), education ($12 million), health ($11 million), and human services ($ 9 million).

Perhaps one of the biggest lessons of the coronavirus has been the social and economic fault lines the pandemic has laid bare. The $1.7 million Philadelphia Worker Relief Fund was created by domestic workers who were unable to benefit from any of the federal or state government aid programs. The fund provided a one-time $800 cash payment. And when schools were closed, and instruction moved online, the digital divide became both readily apparent and an emergency.

At the beginning of August, City officials announced a $17 million plan for free internet access for 35,000 low-income families paid in part by private donors including the William Penn Foundation, the Neubauer Family Foundation, and the Philadelphia School Partnership and, the largest donor, Comcast.

However, as the TRACE project has revealed over the past month, other philanthropic lessons include that :

- Our local nonprofits are both critical providers and vulnerable victims of the pandemic.

- To be effective nonprofit relief, donors have to act quickly and adapt their measures.

- Media attention which especially drives donors to give to nonprofits fades even as need continues or even escalates.

- Some issues are too big for philanthropy such as providing rent assistance as people face evictions.

Project

TRACETrending News