In ‘Faces of Courage’ the collaboration of artist and nonprofit becomes more than documentation

July 1, 2021

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

July 1, 2021

Category: Featured, Long, Purpose

The faces tell the stories. Faces of people struggling to stay in the country they call home, faces of families in sanctuary, faces of people intent on acting to support immigrant rights.

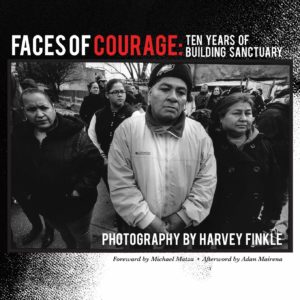

Recently published, Faces of Courage: Ten Years of Building Sanctuary uses the photographs of Philadelphia photographer Harvey Finkle to document a decade of activism through art.

The book bears witness to 10 years of work by the New Sanctuary Movement of Philadelphia (NSM) — an interfaith immigrant justice membership organization that has provided support for Latinx and Black immigrant families in sanctuary and maintains an immigrant-run community fund for bond and legal support — all captured in black-and-white by Finkle.

The book bears witness to 10 years of work by the New Sanctuary Movement of Philadelphia (NSM) — an interfaith immigrant justice membership organization that has provided support for Latinx and Black immigrant families in sanctuary and maintains an immigrant-run community fund for bond and legal support — all captured in black-and-white by Finkle.

This kind of documentation isn’t commonplace for small community organizations like NSM.

“It’s really rare,” said Peter Pedemonti, one of NSM’s co-directors, “especially for a nonprofit. When we first started, we didn’t have a budget to pay a photographer to come [to actions]. Harvey would come to all of them and take amazing pictures, and send them to us for free.”

For the other NSM co-director, Blanca Pacheco, the new book is more like a family photo album than documentation.

“You usually have pictures of your family, your children, your grandchildren [at your home],” she said.”[The book] is kind of like your movement family. It’s really beautiful.”

But how did Finkle end up at the NSM collective actions in the first place?

Toward the start of his career, in the early 1980s, he received a grant to document the movement of Hmong, Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotian people into Philadelphia. His work kept him in and around South Philadelphia, photographing the people who lived there.

“I decided to document all the different groups in South Philadelphia and I began to photograph them,” Finkle said. “And, what I found is the same thing the Jews and the Italians and the Irish found when they came here. They wanted to be safe, right? They wanted to be free to practice whatever religion they wanted. They wanted to make a buck, and they wanted to send their kids to school.”

In 2017 Finkle had a show at the University of Pennsylvania detailing his work with NSM. After that, the book just fell into place. Pedemonti said that the book came out of a natural desire for Finkle and NSM to keep working together.

“Harvey, over time, has become more than just a photographer who comes to actions. He’s become like a member of NSM — and a friend,” Pedemonti said.

The feeling is undoubtedly mutual — he’s donating the proceeds from the book’s sales to NSM.

The book, like the work of NSM itself, has been a team effort.

In addition to Finkle’s photos, there is a forward written by the Philadelphia journalist Michael Matza, who for many years covered the immigrant community for the Philadelphia Inquirer; and Reverend Adán Mairena of West Kensington Ministry — who himself has taken part in actions to protect immigrant rights — wrote the afterword.

Even picking the photos was a collaborative effort.

“There’s not one person deciding what the book is going to be like. I think it’s really a collection of people who give input,” Finkle said.

“I think this one is probably one [photo] I don’t think Harvey actually wanted to put it in [the book], but I was like, ‘we need something in there about accompaniment,’” Pedemonti said. The accompaniment process is one in which more privileged members of the NSM community stand with and in solidarity with immigrants and their families as they attend immigration, criminal, traffic, and family court as well as ICE check ins — not only to offer moral support but also to hold the officials involved in the proceedings accountable.

Most of the text in the book is in both English and Spanish, something that Pacheco really appreciates. “A lot of our members speak Spanish and I really love that they can understand the description of the pictures,” she said. There are also some unconventional additions as well. Steve Parks, founder and director of New City Community Press, which published Faces of Courage, suggested adding a glossary and a timeline.

But the book doesn’t just mark the passage of time — Finkle hinted it might be used in the future as a teaching tool.

It shows a little bit of everything: from the courtroom to marches and protests, to individual portraits. Its earliest photos are from actions in 2009, just a year after the group’s official formation; its most recent document Clive and Oneita Thompson living in sanctuary at First United Methodist Church of Germantown in 2019.

To the people behind NSM, this is far more than just a collection of photos.

When Pedemonti remembers the inception of the book, he thinks of two things: Donald Trump was president and NSM was very busy. In some ways, the timeframe made putting the book together all the better. “I think that’s a very, very healthy way to remember all that the community has done together and the victories we’ve won together,” he said.

Pacheco agrees. “Looking at it, it was just like, ‘Oh my God, we have done so much,’” she said.

“Some of the photos here are from the fight for Philly to be a sanctuary city,” Pedemonti said, “And, you know, when we passed [that], it was one of the best policies in the country.” A later photo — of two police officers dragging protesters Nicole Kligerman and Carmen Guerrero through City Hall — marks when then-Mayor Michael Nutter rolled back just that sanctuary city policy in 2015.

Not only does the book show the various victories over the years, it captures the personalities at the heart of the NSM — its members.

Pacheco was moved to see the mothers and families she knows. “I feel really honored to be working with these mothers who believe that their families, their children deserve better, and are literally working to save their lives and fighting hard,” she said.

The book shows dynamic people, capturing their joy, their strength, their sorrow, even their humor. “So often what we run up against is that people are locked into those images to see immigrants as victims, and as someone to be saved,” Pedemonti said. “And what I appreciate about Harvey is that he presents them as actors in their[own stories], in their full power.”

The relationship between Finkle and NSM's immigrant members is built on trust — trust that he respected people’s boundaries, and trust that he was around for the long haul.

“We have had experiences where somebody wanted to do a project, and it looked very exploitative,” Pacheco said. “I prefer to break the relationship with an outlet than to break a relationship with our membership. It is their story, their lives.”

The trust in Finkle runs deep. He has been invited into people’s homes and into the churches where they are seeking refuge. Pacheco explained that the relationship between Finkle and NSM’s immigrant members is built on trust — trust that he respected people’s boundaries, and trust that he was around for the long haul.

The collaboration between Finkle and NSM could perhaps serve as a model for other nonprofits and other artists. The key, according to Finkle, is that it be a true collaboration.

Speaking about NSM, Finkle said, “I feel embedded with them. I feel a part of them. Over time, it becomes like that. So it’s not like I’m out here looking at this picture. I’m involved in making the picture.”

Trending News